The R1 – South African Bush Rifle

Reading time: 9 minutes

In the wake of the rise of the Soviet Union’s AK-47 and the USA’s litany of rifles during the Cold War, South Africa needed a modern automatic service rifle. After trialling several different guns, the South African government settled on the Belgian FN FAL battle rifle. As a result, the “Rifle R1” was born – the bush rifle of Southern Africa.

By Jade McGee

The R1 vs. FN FAL

FN FAL Inventor: Dieudonné Saive

Whilst the R1 is cemented in South African history, its story has its roots in Europe. The R1 was based on the widely used FN FAL rifle designed by small arms designer Dieudonné Saive.

Saive’s early life remains vague, with little detail and gaps between life events. It’s known that he was born in 1888, in Wandre Belgium, and that his full name is Dieudonné Joseph Saive. It’s also known that shortly after graduating high school, Saive was hired by the Fabrique Nationale (FN) Herstal as a tool designer.

During the First World War, however, he fled to the United Kingdom. Once there, he found a job as a machinist for Vickers Limited.

Following the end of the war, Saive returned to Belgium and was rehired by FN Herstal. Instead of tool design, however, he would become the personal assistant of John Browning, one of the greatest arms designers in history.

As Browning’s personal assistant, Saive worked on several projects. One of the most notable being the GP-35 pistol, or the Browning High Power. Unfortunately, Browning wouldn’t see the success of these designs, as he passed away in 1926. However, Saive oversaw many of these projects to their end.

By 1929, Saive oversaw the design and manufacture of the commercial Browning Automatic Rifle. A year later, Saive became the chief weapon designer for FN. In this new position, Saive went on to improve the M1919 Browning M2. He focused on the operating mechanism, increasing its rate of fire to 1,200 rpm. Later, in 1938, he increased the fire rate to 1,500 rpm.

The Browning High Power became a huge success, especially when Europe was thrown into another World War.

In 1940, following the German invasion of the FN Manufacturing plant in Liege, Saive fled to the United Kingdom, once again.

The Development of the FN FAL

Once in the UK, Saive went on to work at the Royal Small Arms Factory. Here, he recreated production drawings of the High-Power and began developing his design for a gas-operated rifle, the EXP-1.

Once Saive returned to Belgium, the EXP-1 would become the FN Model 1949, which was the basis of the FN FAL. The FN-49 became a popular rifle, adopted for use by several countries, including Argentina, the Belgian Congo, and Brazil.

Despite it being relatively widely used, the FN-49 wasn’t ‘modern’ enough. The West had already begun moving away from bolt action and semi-automatic rifles. Seeing this possibility, Saive had already begun working on an automatic rifle in 1947. This prototype would become the FN FAL.

At first, the FN FAL used the German 7.92x33mm Kurz (short) automatic rifle round. But once FN, and Saive, were introduced to the British .280-inch round, the FN FAL was rechambered to fit this new cartridge. Finally, they settled on the NATO-specified 7.62x51mm ammunition.

Regardless of the calibre, the FN FAL had great potential, becoming the go-to assault rifle for many NATO member states. It later became known as the “Right Arm of The Free World.” Its Soviet counterpart was the AKM, an AK-47 that used milled rather than stamped parts.

The Design

The FN FAL’s short-stroke, spring-loaded piston sits above the barrel and drives the gas system. The gun’s tilting breechblock, or the locking mechanism, is also situated near the barrel.

Despite the FN FAL becoming popular and seemingly revolutionary, its locking mechanism wasn’t altogether new. Like the bolts on several semi-automatic rifles, the mechanism drops into a solid piece of metal in the heavy receiver.

Its gas system has a regulator, found behind the front sight base, which allows the adjustment of the gas systems. These adjustments often occurred in response to any changes in the environmental conditions, ammunition quality and barrel fouling.

Most FALs held 20 rounds of ammo, but the magazine capacity ranged from 5 to 30 rounds.

The recoil spring is housed in different parts of the gun, depending on the variant. Fixed stock versions housed the spring in the stock, whereas folding stock versions housed it in the receiver cover. Thanks to this, folding stock FALs had to have a different recoil spring, receiver cover, and bolt carrier. These FALs also had a modified lower receiver for the stock.

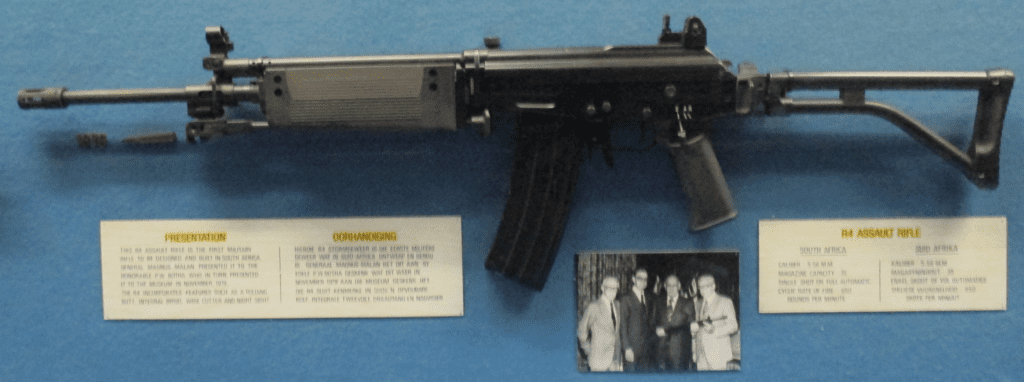

Incorporating the R1 into The South African Defence Force

Like the rest of the world at the start of the Cold War, South Africa needed a modern automatic service rifle. The South African government trialled several other automatic rifles, including the West German G3 and the American AR-10.

However, it’s truly no surprise that they landed on the FN FAL as their weapon of choice. Several design aspects of the FN FAL fit the needs of the South African defence force (SADF) perfectly. So much so that by the mid-50s several local production facilities were set up to begin manufacturing the FN FAL under licence.

This ultimately spurred the establishment of Lyttleton Engineering Works, where the South African variant of the FN FAL was produced, under the designation R1. By 1960, the rifle was formally adopted.

The R1 was a carbon copy of the FN FAL – it had the same overall dimensions, specifications, and construction methodology. it was also chambered to fire the 7.62x51mm NATO standard cartridge, giving it the same accuracy and penetration abilities as the FN FAL.

The R1 Gun Family

The success of the R1 saw the R family of guns growing. Soon, Lyttleton Engineering works began developing several new R-guns, all based on the FN FAL and its variants.

The R2 had a folding stock, coming with the slight design variation seen on other folding stock FN FALs. Soon after, the R3 entered the family.

Because the R3 was specifically intended for the police and security forces, it was only capable of semi-automatic fire.

The family doesn’t stop there, though. The R1 was modified slightly, creating three R1 variants. There was the R1HB, which had a heavy barrel and a bipod, along with the R1 Sniper, which had an accurized repeating fire weapon system.

There was also the R1 Para Carbine. This R1 variant had a shorter barrel than the rest of the R1 family and was generally more compact. It also featured an IR sight, setting it apart from the rest even more.

By 1975, the SADF introduced the R4. While falling under the same family, the R4, and the subsequent R5, wasn’t based on the FN FAL. Instead, it was based on the Israeli Galil assault rifle.

The Bush Wars: Angola and Rhodesia

The introduction of the R1 came at a critical time in Southern African politics, where Cold War tensions were coming to a head.

From the early 1960s, the lower portion of the African continent saw itself rife with civil wars, namely the Rhodesian Bush war, better known as the Zimbabwe War of Liberation, and the Namibian War of Independence. The latter was largely known in South Africa as the Angolan Bush war or South African Border War.

Angola

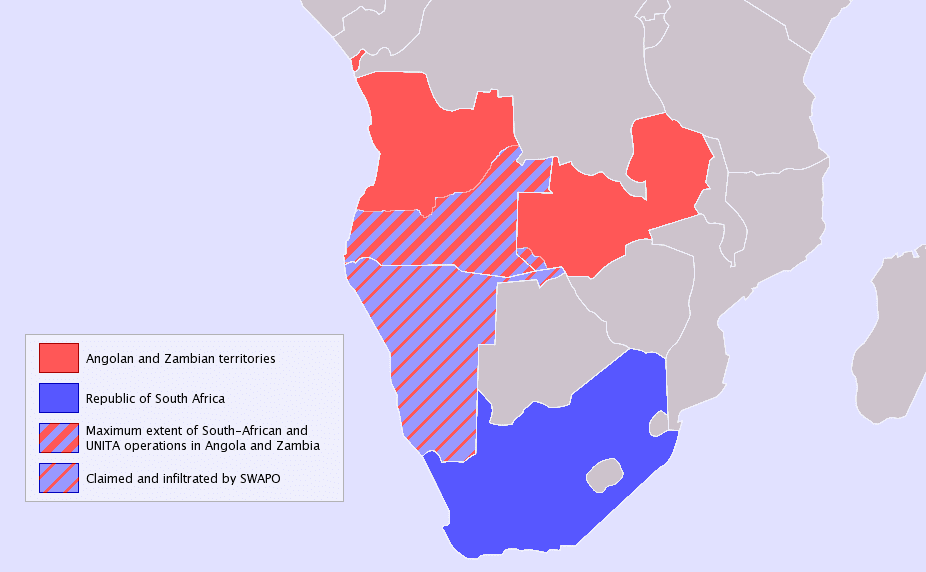

The Border War officially began in 1966 and was fought between the SADF and the People’s Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN). It spread across several African countries, including Angola, Namibia, and Zambia. The war lasted over two decades, only ending in 1989.

This war was closely linked to the Angolan civil war and resulted in the largest battles on the African continent since the Second World War.

Because the R1 battle rifle was the SADF service rifle, it was widely used. Thanks to its hard-wearing design and accuracy, the R1 gave South Africa an edge throughout the war.

Despite the introduction of the R4 in 1975, the R1 remained in service during the war until 1989.

Rhodesia (Zimbabwe)

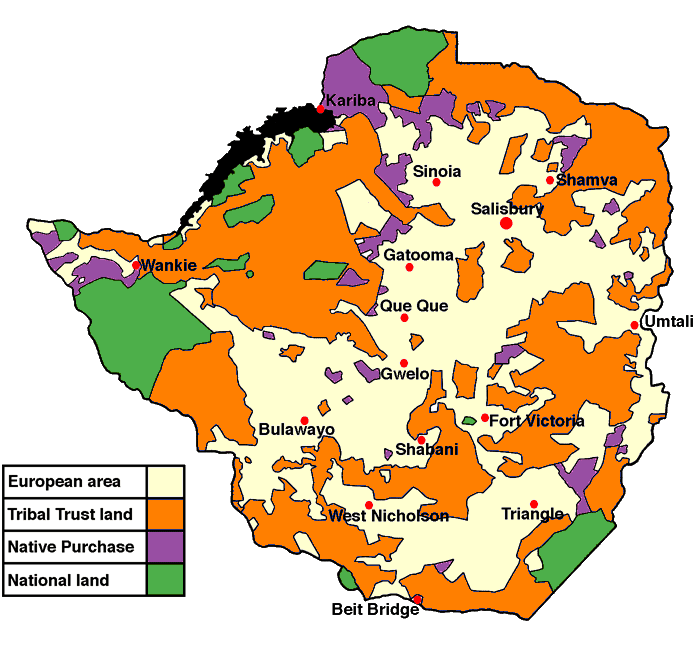

Like the Border War, the Rhodesian bush war was fuelled by Cold War tensions and growing apathy toward the legacy of the Scramble for Africa. From the late 1950s, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) saw the beginnings of civil war. Adding to the tensions were the sanctions and embargos placed on the country by NATO after the Rhodesian government refused to allow black citizens to vote.

By 1964, the conflict was in full swing. It lasted for several years, ending officially in 1979. The three main parties were the Rhodesian white minority-led government, the Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army, and the Zimbabwe African National Union.

As with most Cold War era conflicts, the AKM and AK-47 featured on the battlefield – predominantly in the hands of the Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army, and the Zimbabwe African National Union.

The Rhodesian army, though, fought with the R1s they bought from the South African government. While the R1 aided in the SADF’s victory in the Angolan war, in 1979 the Rhodesian government had to concede defeat.

The R1 may have deep roots in Europe, but it quickly became a quintessential South African symbol. Its use in the Bush wars showcases the resilience of FN FAL design, further proving why it became so popular across the Western world.

Podcast episodes on this topic

Articles you may also like

Frank Cotton and the Invention of the Australian G-Suit

Reading time: 9 minutes

The best-known wartime innovations are the largest, loudest, and flashiest, from humble handguns to the tank. But war has also prompted the invention of fascinating, and less destructive, devices designed not to harm life, but to protect it. One of these was the anti-gravity suit, or g-suit.

Boudicca revolt: Essex dig reveals ‘evidence of Roman reprisals’

The destruction of a “clearly high status” Iron Age village “may represent reprisals after the Boudiccan revolt”, an archaeologist has said. More than 17 roundhouses were discovered in a defensive enclosure at Cressing, near Braintree in Essex. The site was burned down and abandoned during the late First Century AD. “The local Trinovantes tribe joined […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.