Reading time: 8 minutes

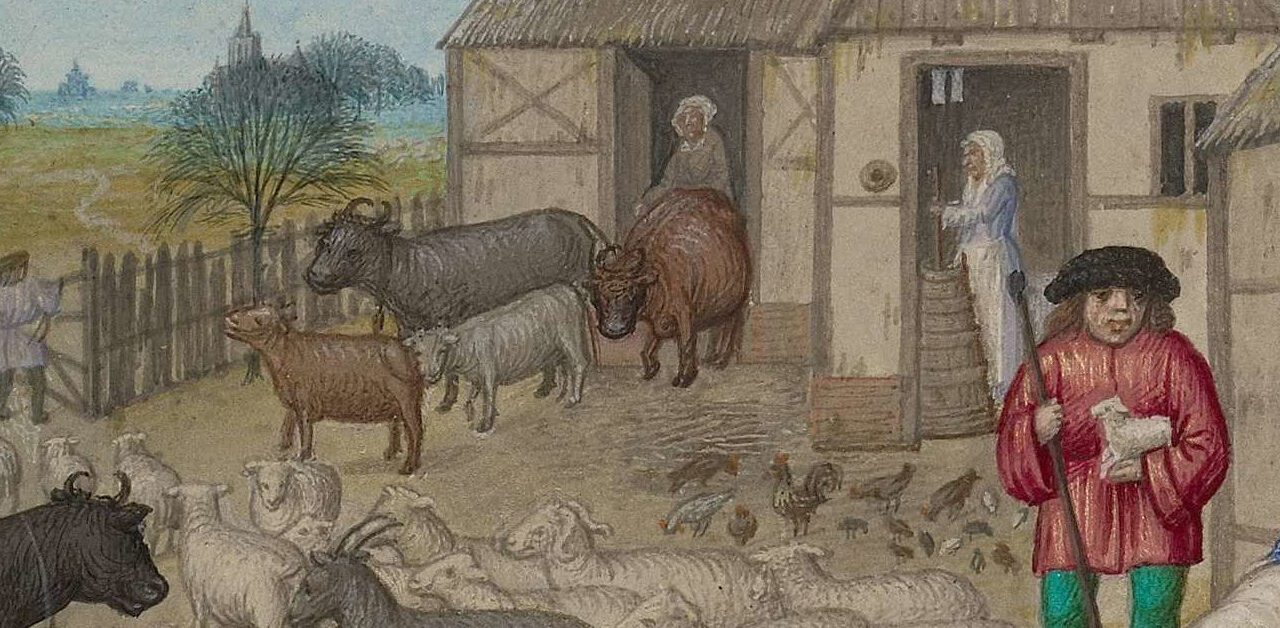

Walking around any British town or village today, it’s difficult to imagine that land might not once have been private. But this was not always the case – for centuries, landless people could access common lands and forests. There they could gather firewood, graze livestock, or grow small crops.

By Morgan WR Dunn

In a time when most people survived by subsistence farming under feudalism, the commons allowed them to eke out a little more food or warmth. While common land is no longer so common, it has a fascinating history which persists to this day.

“The Patrimony of the Poor”: Common Land in Britain

Land was first set aside as commons in the Anglo-Saxon period, beginning in 450 CE. This was an era when early British kings were ascendant and the roots of later feudal social structures were being planted. Common lands (or “commons”) came into existence as Anglo-Saxons moved throughout England, regarding their conquered territories as prizes held in common and divided between them.

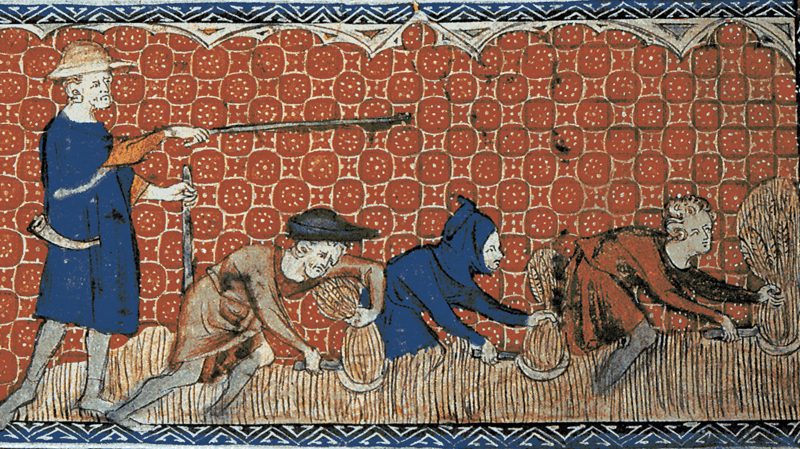

Grazing, hunting, fishing, and gathering wood or other natural resources were shared. This system varied depending on local customs and was governed by local assemblies, or “moots”. Anglo-Saxon records mention rights of common, like “herbage,” or grazing, and “estovers,” or allowances for wood collection.

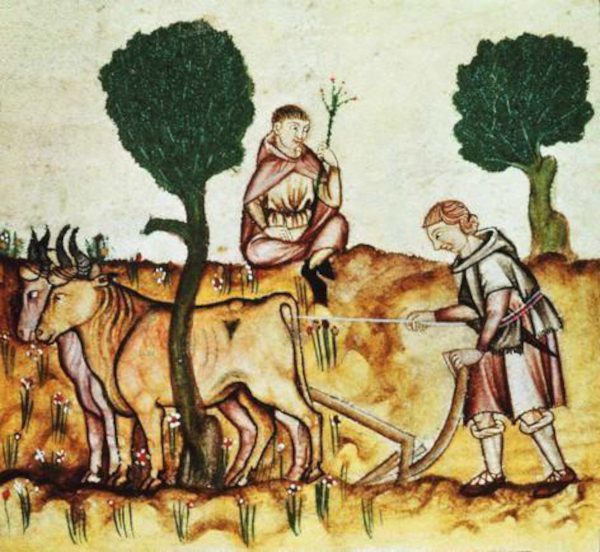

Before technologies like crop rotation, modern irrigation, and drainage existed, each manorial house in Britain had attached to it plots of ground that were less productive than valuable farmland. Peasants, merchants, artisans, and others could access this land – land held “in common,” or for all – for their own needs. Land usage scholars have noted that, since this was a customary practice, the rights accompanying it and the rules governing it differed from place to place.

The Rights and Customs of Commoners

The first major challenge to this way of life came with the Norman Conquest in 1066. While royal forests, or areas of land (not always wooded) reserved for the use of rulers and nobles, had become an established concept under the Anglo-Saxons, King William I (“the Conqueror”) drastically expanded their size and use. The Normans introduced Forest law. Under it, anyone caught hunting, collecting wood, or even foraging on forest land would be subject to severe penalties ranging from punitive fines to death.

Norman laws seriously depleted the area available to commoners, since most people spent their entire lives living in a small geographic area and couldn’t expand elsewhere. Nevertheless, William, like the Anglo-Saxon rulers before him, allowed the landless class to use commons outside the royal reserves, as removing their ancient customary rights would have led to serious unrest and likely paralysed the early medieval economy.

These rights included that of “pasture,” or grazing livestock like cattle, sheep, and horses, although few peasants could own many, if any, such valuable animals, and the number of any animal a household could keep was restricted. Another was “estovers,” an allowance for firewood usually collected from small trees or fallen branches. Other rights included “turbary,” or cutting turf or peat for fuel, and “pannage,” setting pigs loose to forage in woodlands.

Access to common lands was always a privilege granted by whichever noble held the actual title to them. It could thus be taken away if one commoner was thought to be taking more than their share. Commons could also be “stinted” (restricted) when growing populations expanded to prevent them being ruined.

Common Land Systems Across the British Isles

England: the Open Field System

The prevailing method of organising common land in England was the open field system. Under this arrangement, several large plots of a noble’s land were set aside for growing crops, several for hay, and some for grazing and gardening. Crops were rotated to avoid soil exhaustion. Peasants had to exchange work or rent to live on sections of the land, but this also meant they could support themselves with small crops and livestock of their own. “In the open field village,” the economist Gilbert Slater wrote, “the entirely landless labourer was scarcely to be found.”

The open field system, possibly based on the older Celtic field system, persisted for centuries, with gradual consolidation and enclosure, the restriction of land from common use, diminishing the stock over time. By the time common land effectively came to an end in England in the mid-19th century, the few remaining open field areas were in the North.

Ireland: Commonages and Clan Lands

In Ireland before the eventual English conquest, land, while administered and controlled by a lord, was owned collectively. It was divided into plots for leaders and aristocrats, but one section, the Cumhal Senorba, was set aside “for the maintenance of the poor, old, and incapable members of the clan,” and another, called “the Fearan Fine, or tribe’s quarter, was retained as the common land of the whole clan.”

This system came to an end in the aftermath of Oliver Cromwell’s conquest of Ireland. As a result of this, most of the island was confiscated by English landlords, who rented plots to peasants as in England. When late 19th century reforms did away with this arrangement, plots called commonages became the normal mode of designating Irish common land.

Scotland: Run-Rig and Other Commons

Before its union with England in 1707, Scotland had a variety of types of common land. These included Crown Commons, or lands held by the king which anyone could use much like English commons, common mosses where the public could cut peat for fuel, and the run rig system.

Under run rig, land was divided into strips called “rigs” which were rented out, often by intermediaries called tacksmen who sublet the land. Rigs would occasionally be reallocated to individual farmers, and in some areas of the Scottish Highlands they were connected to common grazing grounds open to all nearby tenants.

Enclosure: the End of the Commons

Commoners won a significant victory in the struggle over land rights in 1217. The Magna Carta, signed by King John in 1215, had placed substantial limits on forest law and the monarch’s rights within it. Two years later came the Charter of the Forest, which further relaxed restrictions and also enshrined pannage and agistment, the grazing of cattle specifically, in law.

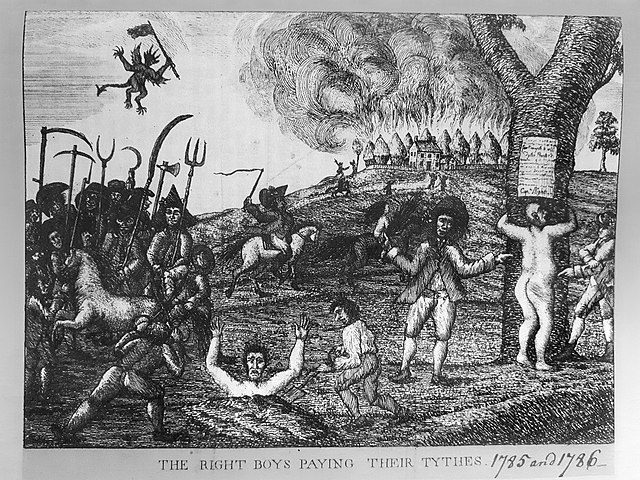

But there were always those who sought to close the commons off and turn a profit from them. This process is known as enclosure. It had already appeared in the medieval period when the 1235 Statute of Merton enabled nobles to combine plots into single holdings.

Landowners sought to consolidate fields and convert communal lands into private holdings for more profitable agricultural uses. This accelerated in response to the growth of the wool trade during the Tudor era, which made pasture land for sheep extremely valuable.

Over time, landowners gained more and more power as traditional peasant customs lost ground and as laws transferred more and greater rights away from commoners. This trend finally culminated in the Inclosure Act 1773, which gave landowners the right to enclose land by petition with the consent of those who depended on it (this clause was often ignored) and is still in effect today. By the beginning of the 20th century, nearly 110,000 square miles had been enclosed. Today, 1.3 million acres, or just 2.1% of Britain’s total area, is common land. And while many of the rights and privileges once available to the public in these areas are long gone, many survive, perhaps most meaningfully in the form of areas of natural beauty like the Yorkshire Dales and Dartmoor in the southwest.

Articles you may also like

The 1919 Egyptian Revolution

Reading time: 8 minutes

The events of 1919 in Egypt show how the First World War played a crucial role in affecting the country’s history after the war ended.The interwar years saw a political dance take place between the British, Egyptian nationalist politicians, and the Egyptian king, who mistrusted the nationalists. It would take the upheaval of the Second World War and a further Egyptian Revolution in 1952 for the British to leave Egypt. The last British troops left in June 1956, although the Suez Crisis later that year saw their temporary return. While the Egyptian Revolution of 1919 did not secure Egypt’s freedom from foreign rule, it was an important step towards that goal. After 1919, the British had to consider the strength of Egyptian nationalism and deal with nationalist politicians. The Revolution was an inspiration for other anti-colonial struggles across Africa and Asia. The events of 1919 in Egypt show how the First World War played a crucial role in affecting the country’s history after the war ended. The negative effects of the war on Egypt unleashed powerful forces in Egyptian politics and society that could not be ignored.

The Confessions of Nat Turner, The Leader of the Late Insurrection in Southampton VA – Audiobook

By Thomas R. Gray THE CONFESSIONS OF NAT TURNER, THE LEADER OF THE LATE INSURRECTION IN SOUTHAMPTON VA – AUDIOBOOK This is a detailed description of the massacre that took place on August 21-23, 1831 that became known as Nat Turner’s Rebellion. Nat Turner himself relates the events to the author from his jail cell […]

German spies in South Africa during WWII – The enemy within

Reading time: 5 minutes

The story of the intelligence war in South Africa during the Second World War is one of suspense, drama and dogged persistence. South Africa officially joined the war on 6 September 1939 by siding with Britain and the Allies and declaring war on Nazi Germany.

South African historians have largely overlooked the intelligence war, partly because of the apparent paucity of reference sources on it. This lack of attention prompted me to investigate the matter further. The result was my book Hitler’s Spies: Secret Agents and the Intelligence War in South Africa.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.