Reading time: 10 minutes

“We choose to go to the moon in this decade, and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.” President JFK’s inspiring words sparked the race to the moon.

By Jade McGee

The idea of landing on the moon seemed impossible. But just seven years after his speech at Rice University in 1962, the Apollo 11 mission succeeded in landing human beings on the moon.

The moon landing is often seen as an incredible, inspiring adventure, but it was a rushed effort, with plenty of drama and action behind the scenes. From intense pressure, and major scientific debate, to almost calling off the entire mission, minutes before the finish line. This is the story of events before that giant leap for mankind.

The Need for Speed

Our tale begins in 1947, long before the space race. When test pilot Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier, he proved that the seemingly impossible can be possible, if you keep trying. That lesson, along with the massive scientific and technological bounds achieved by the breaking of the sound barrier, carried NASA to the moon.

Over the next decade, test pilots continued to go faster, higher, and further, having intense determination to succeed. Hence NASA’s decision to hire test pilots as astronauts.

During this time, the USSR was also putting their test pilots to the test, constantly wanting to one-up the USA. This was the beginning of the Space Race.

In 1957, the USSR succeeded in spectacularly outdoing the US. They were the first to launch an artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, into space. Given the heightening Cold War tensions, the world began to fear the Soviet’s newfound ability to deliver nuclear weapons over intercontinental distances. This also threatened the USA’s sole superpower status.

As a result, President Eisenhower created the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Their first mission was simple – launch a man into orbit. This was known as Project Mercury.

Unfortunately, the USSR beat the USA again. In 1961, Soviet Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space after completing an orbit around the Earth. A few weeks later, on May 5, 1961, Alan Shepard entered earth’s orbit for 15 minutes, becoming the first American in Space.

20 days later, President JFK addressed the US Congress, declaring that a manned mission to the moon should be accomplished by the end of the decade. A year later, he gave his famous speech at Rice University, where his inspiring words, “we choose to go to the moon” ramped up Space Race efforts.

The Race to The Moon

Whilst inspiring, JFK’s speech faced some backlash. A handful of scientists and mathematicians saw the moon landing as either a waste of time or something that couldn’t be achieved in a few short years.

However, before his bold statements, Kennedy had covered his bases. In 1961, he approached the USSR’s premier Nikita Khrushchev, proposing a joint effort to land on the moon. Khrushchev, of course, turned him down. Despite this, JFK forged ahead. He tasked his VP, LB Johnson with seeking advice from some of the greatest minds at NASA.

Johnson turned to Wernher von Braun, a German engineer who now worked for NASA. His employment was controversial, thanks to his involvement in the V2 rockets of WW2, but his expertise sped up the race to the moon.

Von Braun highlighted that a three-man mission to the moon could be achieved by 1965, but an advanced rocket would be required, one that neither superpower had. He thus advised NASA to forge ahead with an “all-out crash programme” that could see the moon landing being accomplished by 1968.

And so, JFK made his declaration, and ultimately, NASA was tasked with landing astronauts on the moon before 1970. The effort was named Project Apollo.

Despite the naysayers, the gargantuan budget, and the untimely death of JFK, Project Apollo chugged on.

Decisions, Decisions

The first step in the Moon race was deciding how to get there. NASA scientists came up with three options; the direct method, the earth orbit rendezvous method, and the lunar orbit rendezvous method. All three had their issues and it took 12 months for NASA to finally choose the third method.

Once that decision was made, they needed to determine what rocket to use. That’s where Wernher von Braun makes another appearance in this tale. With the technology and know-how from his development of the WW2 V2 rockets, von Braun was able to produce a launcher that could take the USA to the moon. This launcher was the Saturn V.

The Technologies Behind the Moon Landing

Next, came the designing of the spacecraft that would take USA to the moon.

For the mission to be successful, the Apollo spacecraft had to be split into three. Under Project Gemini, the three key components were designed and developed. Gemini also produced what many call the “fourth astronaut” – the software that helped the moon landing succeed.

The three components of the spacecraft were the command module (CM), a service module (SM), and a lunar module (LM). The CM, which had a cabin to house the three astronauts, would be the only component to return to earth. As the name suggests, the SM serviced the CM. It supported the main component with propulsion, electrical power, and water and oxygen.

The LM, though, would be the star of the show, as it would take two of the three astronauts to the moon. It had two stages: a descent stage, and an ascent stage. The latter would propel the two astronauts back into lunar orbit. A key part of the LM was its computer software. This software aided in navigation and guidance. Without this software, landing on the moon safely would have been near impossible.

The Apollo Missions

In 1966, the Apollo programme launched several missions. These aimed at testing the technologies and spacecraft designed by Project Gemini. The initial test flights were unmanned, and all succeeded.

The first manned test flight was meant to be Apollo 1, on 21 February 1967. The goal of this flight was to test the CM and SM in a low Earth orbit. Unfortunately, the mission never flew. A cabin fire broke out during a rehearsal test on 27 January 1967, killing all three crew members.

The next three Apollo missions remained unmanned. But in October 1968, the first manned mission, Apollo 7, flew with no hiccups. This mission aimed to test the command and service module (CSM) in the Earth’s orbit.

Apollo 8, another successful manned mission, put the CSM through its paces in Lunar orbit. By March 1969, the lunar module was ready for testing. During the Apollo 9 mission, the LM entered Earth’s orbit and was another successful mission. The Apollo 10 mission acted as a dress rehearsal. This manned mission took the LM to Lunar’s orbit and flew the LM down to 15 km (50 000 feet) from the Moon’s surface.

All was ready for the Apollo 11 mission on 16 July 1969.

Apollo 11

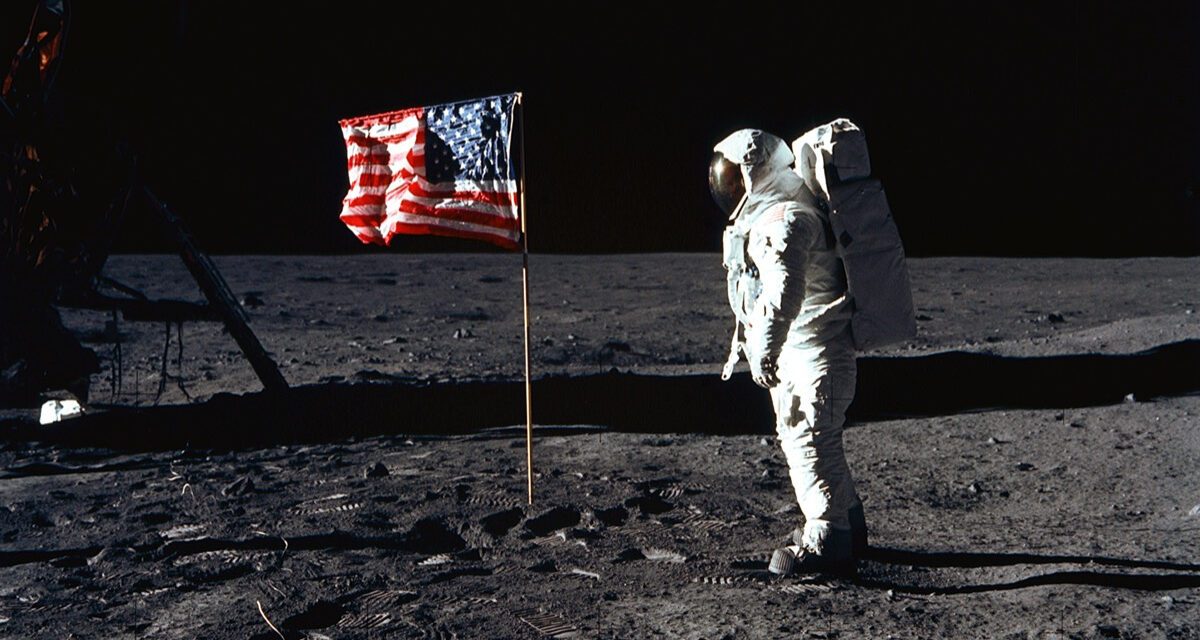

On the morning of 16 July 1969, the world waited with bated breath. Just after 13:30, UCT, Apollo 11 lifted off, carrying Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins. After 76 hours, Apollo 11 made it into lunar orbit. It orbited the moon around 30 times, giving the crew an opportunity to survey their landing spot – the southern Sea of Tranquillity.

While the first leg of the mission was stressful, it was the easiest part.

On 20 July, a few minutes before 13:00, UTC, Armstrong and Aldrin entered the Lunar Module Eagle. For the next few hours, they prepared for the lunar descent. At around quarter-to-six, Eagle separated from CSM Columbia, leaving Collins behind.

From Columbia, Collins examined Eagle, ensuring all was well, as Armstrong exclaimed, “The Eagle has wings.”

From this point, though, both spacecraft were out of range, leaving Mission Control in Houston blind. Mission control’s flight controller Gene Kranz describes the atmosphere of NASA and Mission Control as being preoccupied. The rising tensions were due to pressure placed on the young team at Mission Control – there were three potential outcomes; land, abort, or crash Apollo 11.

Unbeknownst to mission control, Eagle was flying toward the Moon’s surface a lot faster than it should be.

Once Mission Control made contact, however, another problem arises – the communications systems aren’t good enough. Neither party can make direct contact, increasing tensions further. To get the necessary data to make the right calls, Mission Control must use Collins as a middleman.

Whilst not ideal, it works.

As Eagle began reaching the critical Go-No-Go stage, all contact is lost. The Go-No-Go is delayed by just 40 seconds. With the slightly “stale” data, Mission Control gives a thumbs up for “GO.”

13 Minutes to The Moon

Again, the “GO” is transmitted via Collins. And so, the 13-minute descent begins.

But as Mission Control finally gets better signal, another problem arises. Inside Eagle and on Mission Control’s controls, the LM guidance computer (LMGC) begins spitting out alarming warnings. Mission Control confirms that Eagle is traveling too fast, rapidly nearing its abort limits.

Luckily, it stays at its speed, with no changes, meaning the descent can continue, safely Mission. The planned landing location now becomes an issue. Because Eagle had been moving faster than it should have, it will no longer land at Tranquillity Base. Instead, the only spot seems to be a rocky, dangerous area.

As Eagle keeps descending, the LMGC continues to spit out alarms, quickly becoming overloaded. Mission Control gets a report from the young experts who designed the software. The alarms aren’t critical, the mission is still “GO”. But the dangerous landing site is now becoming an even bigger issue.

So, Armstrong takes matters into his own hands, literally. He and Aldrin flip Eagle into manual operation, and Armstrong begins hand flying. Unfortunately, this bold move comes at a price – fuel.

Fuel consumption kept changing, adding to the mounding pressure. Armstrong knew he needed to land, sooner, rather than later. With 90 seconds left of fuel, and 30m to go, he needed to decide quickly. He found a small, clear, and level patch in the nick of time, and put the LM down.

The Eagle Has Landed

Eagle landed safely on the moon at 20:17, UCT. If Armstrong had waited another 25 seconds, they would have had to abort the mission. Armstrong radioed into Mission Control, “Houston. Tranquillity Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

Six hours and 39 minutes after landing – thanks to the various necessary checks – Aldrin and Armstrong slid into their suits and depressurized Eagle and opened her hatch. As Armstrong stepped from Eagle’s last foot bed, he declared “That’s one small step for man… one giant leap for mankind.”

The USA had done it.

They had landed on the moon, before the USSR, and before the decade was up. Despite the trials and tribulations leading up to this historical event, including the gruelling last 13-minutes, the mission was complete.

While the tale of the race to the moon ends there, Armstrong’s words rang true. Thanks to the race to the Moon, and the Apollo 11 mission, the world was thrust into technological advancement. A giant leap, indeed.

13 Minutes to the Moon Podcast Series

This excellent series examines the story of the people who made Apollo 11 happen.

Articles you may also like

CHICKENHAWK – BOOK REVIEW

Reading time: 1 minute

A look at the novel Chickenhawk, Robert Mason’s bestselling account of his service as a chopper pilot in Vietnam–a no-holds-barred autobiography that reveals the war’s shattering legacy in the heart of a returning vet.

Rome’s Greatest Technological Developments

Reading time: 7 minutes

Rome.

The capital city of modern day Italy, and one of the most famous, successful and longest-lasting empires to ever exist on planet Earth.

The Romans, both in the eras of the Roman Republic and the Empire, had a knack for stealing, adapting, and improving upon technologies, tactics, and ideas they encountered from other cultures – often those they fought, ranging from the Etruscans to the Greeks and Persians.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.