Reading time: 5 minutes

On June 3 1992, the High Court of Australia handed down its decision in the long-running case of Eddie Koiki Mabo and his compatriots from the Torres Strait island of Mer. Together they challenged the authority of the Queensland government to claim not just sovereignty but also ownership of the land comprising their ancestral home.

By Kate Galloway, Bond University

What happened?

Queensland annexed the Murray Islands through the Queensland Coast Islands Act of 1879. The court had to determine the effect of this annexation on the rights of the Meriam people to their land.

In its argument, the state claimed that on becoming sovereign over this territory, it derived ownership of all the land comprised in it – including the island of Mer.

This concept, known as universal and absolute beneficial crown ownership, was derived from the idea that Australia was “terra nullius”. According to international law, this implied that a territory was uninhabited. Consequently, England could lawfully claim sovereignty over that territory.

Similarly, under English law, Australia was deemed to be “settled and uninhabited”, and therefore English law was fully imported into the new territory.

A feature of this law was that the Crown was the absolute owner of all land — a relic of English feudalism. If, by law, the Crown was the absolute owner of all land, there was simply no possibility of recognising any other type of landholding, including that of Eddie Mabo.

By contrast, Mabo argued that, despite the state’s claim to sovereignty, he and his people retained ownership over the land. The basis of this argument is the well-known reality that Australia was not uninhabited at the time of colonisation. To maintain a law based on this outdated fiction would be unjust.

The court agreed. Although it could not upset sovereignty, the fact of sovereignty could no longer support the state’s claim for absolute ownership of all land. It recognised a new category of territory – one that was “settled but inhabited”.

As an inhabited territory, the original inhabitants – including Mabo and his community – retained ownership of land.

However, the state did have the power as sovereign to extinguish pre-existing ownership rights. But the Anglo-Australian legal system would continue to recognise those rights until they were extinguished. This is known as native title.

What was its impact?

Although in the early days the Mabo decision generally seemed welcome, it was not long before it became increasingly divisive.

Many celebrated a huge victory for justice for Indigenous Australians. Some of this enthusiasm foresaw a new age of reconciliation, perhaps even a new republican constitution.

But, increasingly, in the months after the decision, many opposed what they saw as the decision’s support for the “white guilt industry”. Mining companies asserted that a “flood” of land claims would inhibit mining in Australia contrary to the national interest. The Australian Mining Industry Council (now the Minerals Council of Australia) took out full-page advertisements to that effect.

Adding to the panic, Victorian Premier Jeff Kennett claimed that Australian backyards were under threat from Aboriginal land claims – he has since admitted he was wrong.

The decision has remained important to Indigenous communities throughout Australia, notably because Anglo-Australian law now officially recognises the prior existence of Indigenous peoples. No longer is Australia “terra nullius”.

However, there have also been Indigenous voices expressing criticism of the decision. Noted scholar Irene Watson observes:

Post-Mabo most people believe we have gained justice. We are still working for the same goal, land rights and self-determination, but we are also working harder than ever before, for now we are also working on unmasking the illusion; the illusion that “the blacks have got it all”.

What are its contemporary implications?

The decision had a huge impact on Australian life. However, regardless of which side of the debate you might be on, it is clear that our institutions and society can cope with such apparently enormous shifts.

Some suggest the Mabo decision did not go far enough to achieve real justice. This indicates that, despite the perhaps inevitable argument that follows profound change, we can afford to be aspirational in embarking on reform efforts.

It is also clear that divisive language, such as that of the debate that followed the Mabo decision (and since), is unnecessary. Knowing that our institutions can withstand the “shock” of change surely means we can engage in a well-modulated and respectful public discussion to achieve it.

Finally, we clearly cannot be complacent following even apparently significant advances in the law’s approach to Indigenous Australians’ claims for justice. There remains work to be done; any single advance will not be sufficient.

To fulfil the promise of Mabo, to advance justice for Indigenous Australians, we need a suite of reforms embracing law, policy and the economy.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about Mabo and Native Title

Articles you may also like

How the Thirty Years’ War Weakened Spain

Reading time: 5 minutes

The Thirty Years War (1618-1648) wasn’t a conflict as much as a vortex that sucked every major European power into it only to spit them out battered and bruised a few years later. We have talked about how it started in Prague and how Sweden got involved; in this article, it’s Spain’s turn.

General History Quiz 169

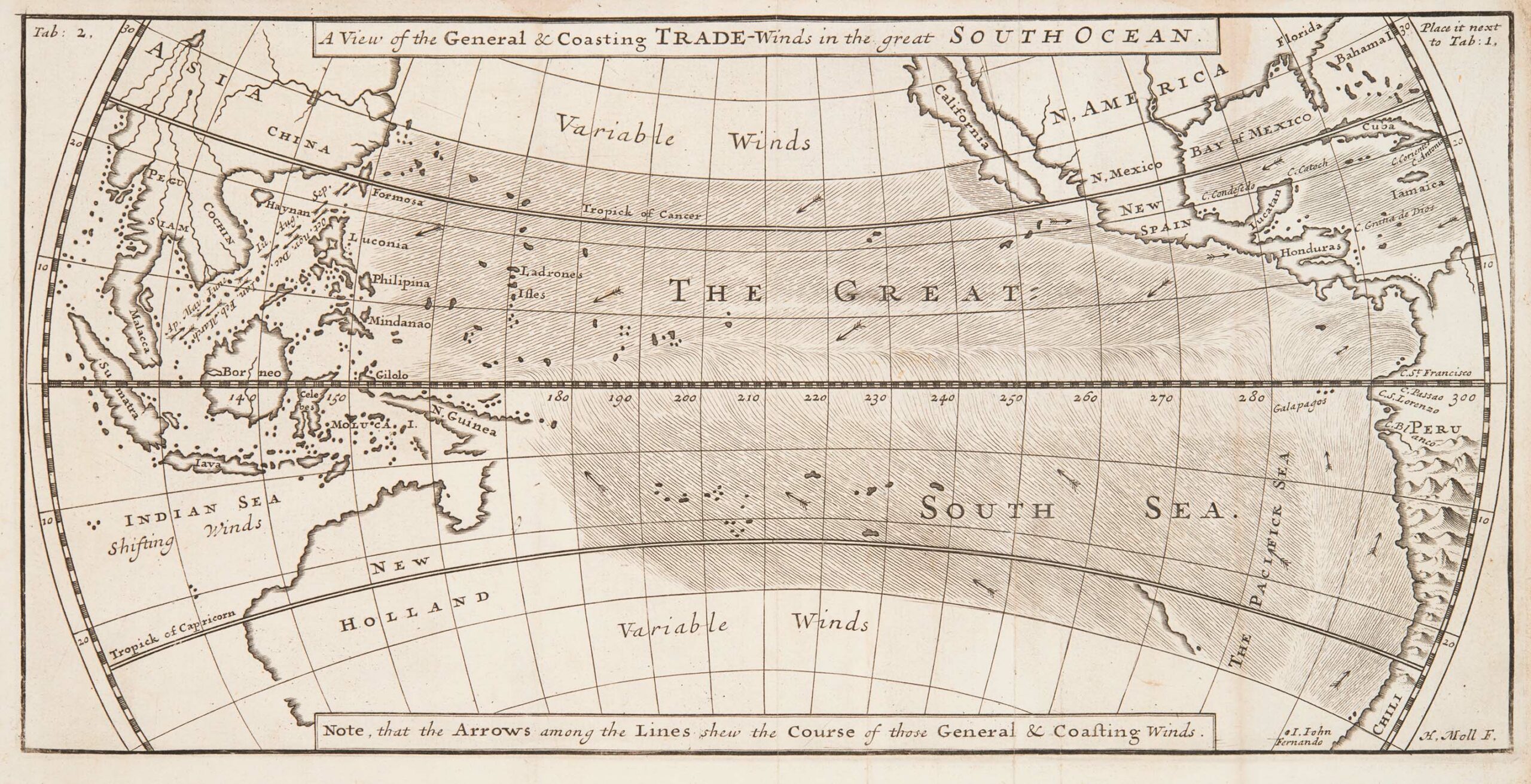

1. Which European power controlled the Manila Galleon trade across the Pacific ocean in the 1600s?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

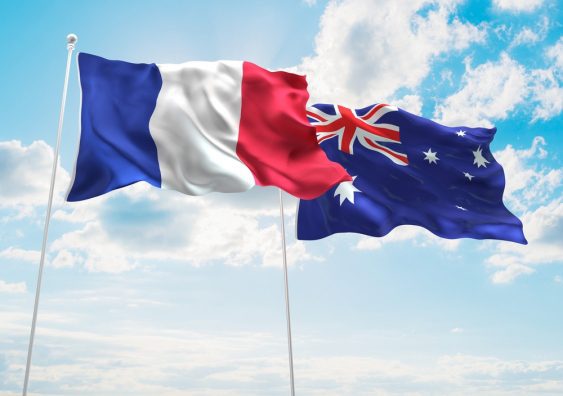

Australia’s long dread of France in the South Pacific

Reading time: 13 minutes

A striking duality drove Australia’s thinking about France in the 20th century. Expressed as a chant it went: In Europe, Good! In the Pacific, Bad!

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.