Reading time: 7 minutes

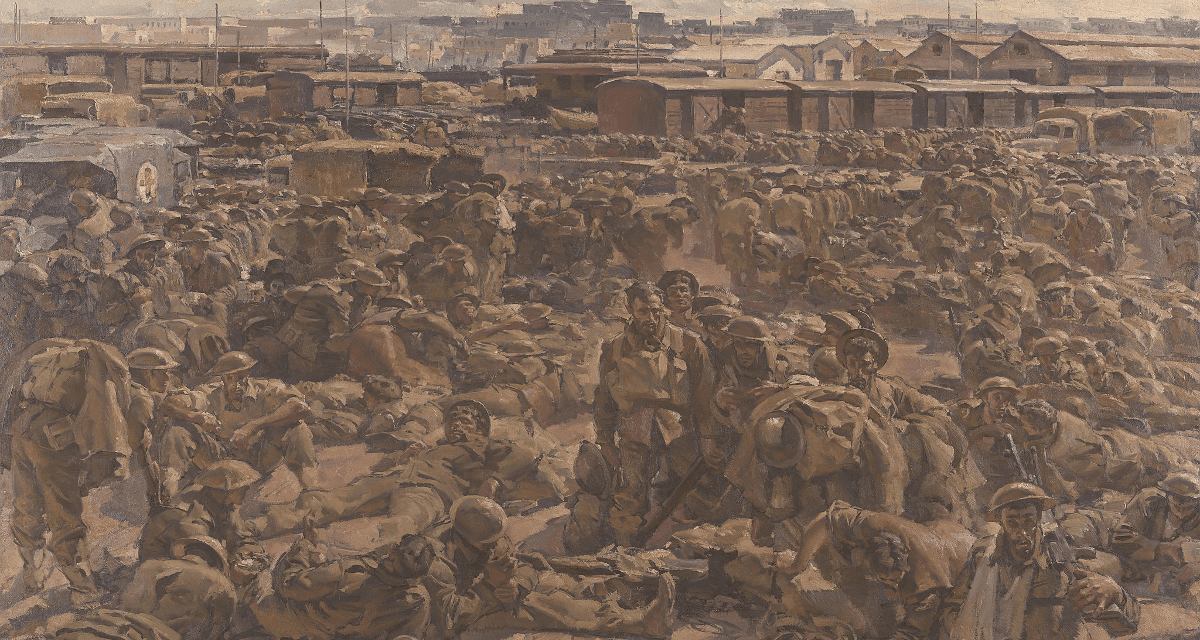

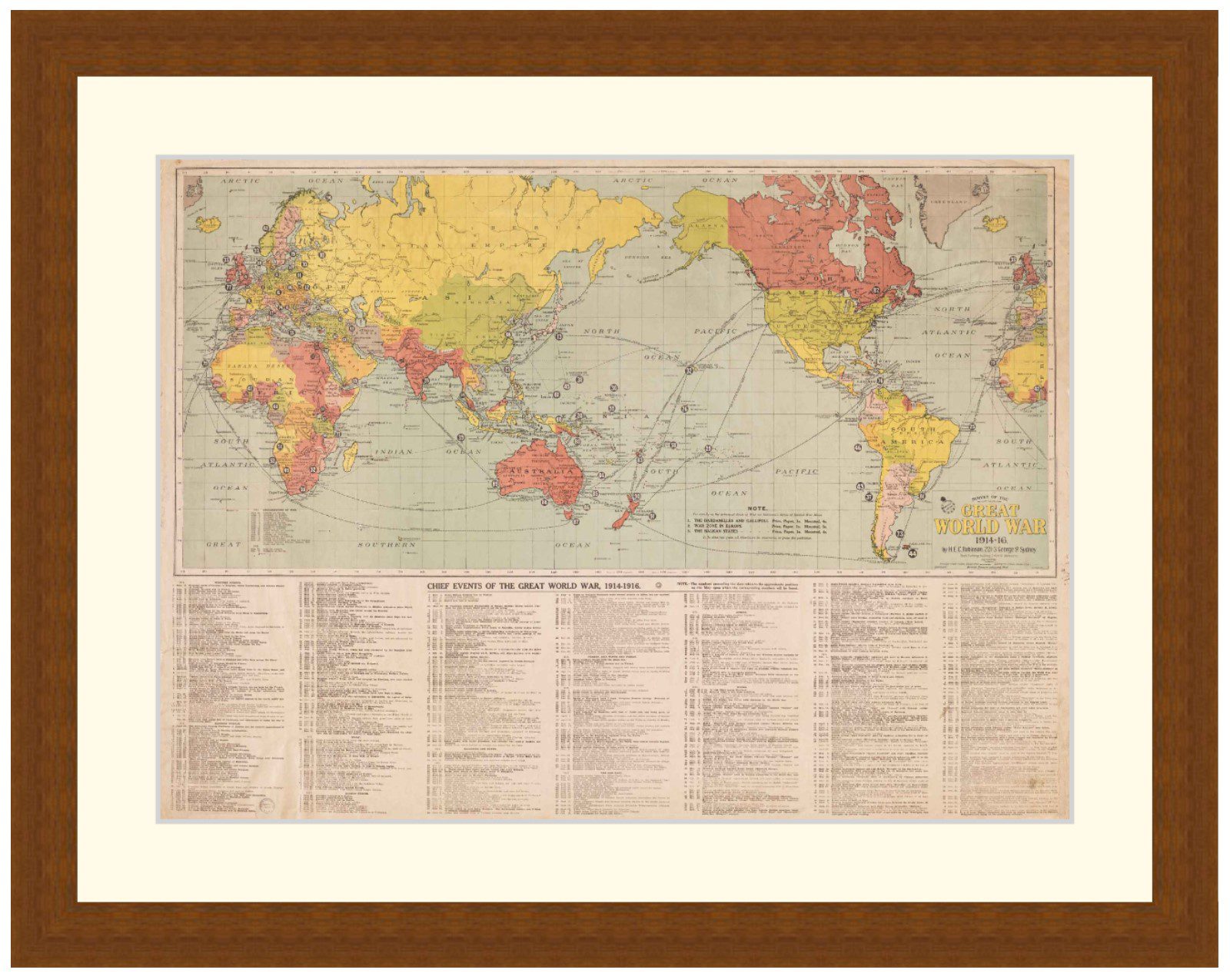

The Battle of Greece is a story of grit, determination, and sheer bloody-mindedness as an outnumbered force of British and Anzac troops successfully delayed the tide of Germans invading the Mediterranean country. The goal was to delay the advance long enough to allow for Allied troops to be evacuated from Greece, ready to fight another day.

By Fergus O’Sullivan

In this article, we’ll go over the stories of Australian servicemen who experienced the evacuations from Greece and Crete firsthand. As is always the case with articles about Australians in the Med during WW II, we use their words as found in their testimonies in the Australians at War Film Archive, a massive trove of interviews with Australian veterans mostly conducted early this century.

The evacuations

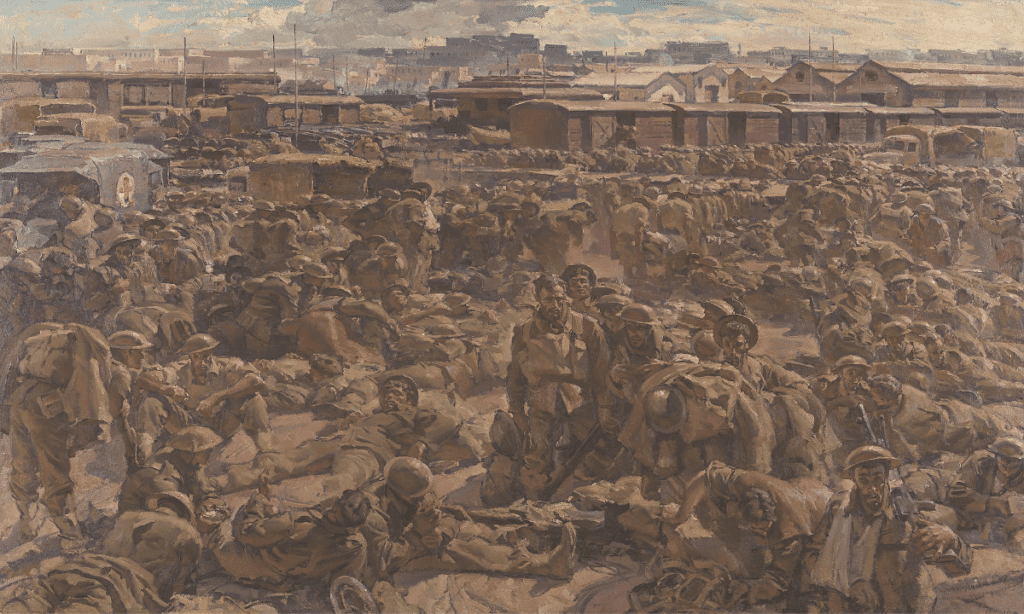

When the Germans invaded Greece in April 1941, Allied command knew it was outmatched from the start, and the expeditionary force — mainly British and Anzac troops, numbering roughly 60,000 — was in danger of being captured. The plan was to delay the German advance in the rough terrain of the Greek mountains using predominantly light forces. Meanwhile, the bulk of the men and materiel made their way to pick-up points along the coast to be evacuated by the Royal (and Australian) Navy.

You can read in detail about one such delaying action in our article about the battle of Pinios Gorge, where a several units of Australian and New Zealand infantry and artillery held back a much larger force of Germans, including armour.

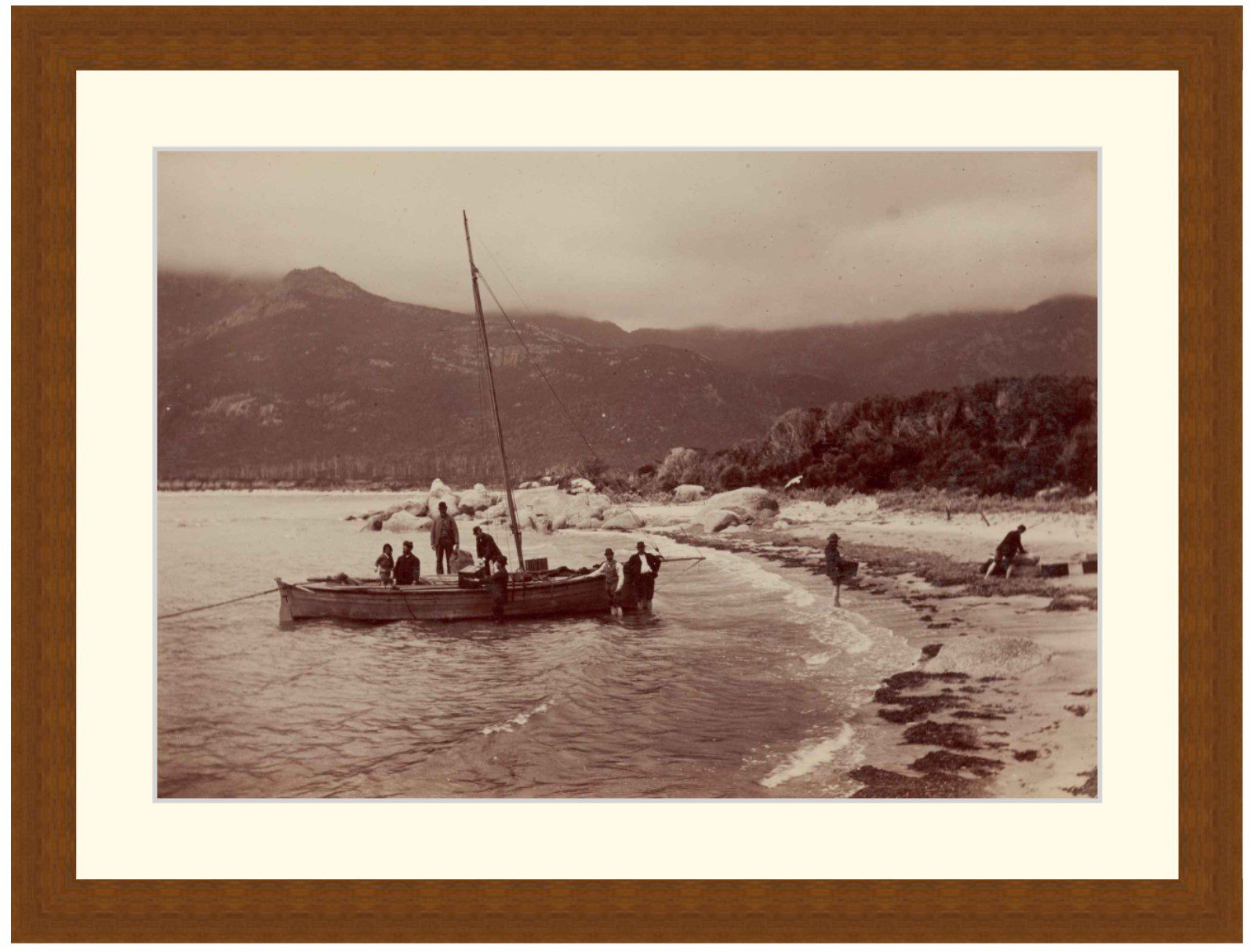

The plan for the evacuation itself was a two-step affair. First came the evacuation from the Greek mainland, with thousands of soldiers being ferried to Allied-held Crete, which is only about three or four hours of sailing under full steam, according to the interviewed sailors.

Knowing that the Battle for Crete was an inevitability, as was the fact that the island would fall to the assaulting Germans, the second step was to have the Royal Navy and Royal Australian Navy move soldiers from Crete to Alexandria, where 60,000 men would be a welcome addition to the troops holding back Field Marshal Rommel from taking over Egypt — like in the first battle of El Alamein.

Making up the rearguard: Greece

Though the plan was straightforward on paper, the reality was a great deal more chaotic. For one, while the rearguard action being fought was successful, units didn’t always manage to stay together, so they arrived in dribs and drabs whenever and wherever they could. Another issue is that many of the evacuations took place at night. Patrick Bridges from Coffs Harbour, NSW, who served aboard a RAN ship, explains:

[…] night time was the best time. See, you tried to get as far away from the mainland in dark because in daylight hours you were closer to the enemy airfields you know. More chance of getting action. So we worked like as fast and as hard as we could to get the troops on board of a night. It wasn’t always successful. [We ran] into a landing barge in Nortlia harbour […] I think it was full of troops then. […] we never found them anyway. Things happen in the dark.

Patrick Bridges

Sometimes conditions were so bad that ships were unable to make their pickups, like in the story told by Brian Sheedy from Melbourne, who likewise served in the Royal Australian Navy:

We went up one night for another evacuation at Kalamata, right down the south, very close to Cape Matapan [site of a major naval battle]. And there were 5,000 troops there. We went in there in the dark. Anyway, we could see the German guns at the back of the town firing into the township. It’s very close to Italy there and our captain decided he was not going to go in and pick them up. Our captain was a Royal Navy captain, not an Australian. He turned the ship around. We had two destroyers with us… because apparently he thought, with the fires in the town and the ship standing there […] it made a beautiful target in silhouette for an Italian submarine. So he aborted.

Brian Sheedy

The 5,000 men in question were soon captured by the Germans, which, Mr. Sheedy says, “caused animosity in Alexandria […] There were quite a few brawls took place between the Royal Navy people who reckoned that the Australians, in the vernacular, had dogged it.”

The question remains whether even if Mr. Sheedy’s captain had decided to pick up the troops whether they all would have fit. With so many troops needing to get out of Greece, space came at a premium, as Mr. Bridges explains:

Once you’re loaded you could only take so many. You did the best you could, you put them anywhere you could place them. Standing, lying, walking anywhere. But as I said it was only a matter of hours before you were back into Crete. So you got them on the best way you could and got them off the best way you could as quick as you could. There was no comfort involved. Oh you made them as comfortable as possible but you put them everywhere you could, you know.

Patrick Bridges

Panic

With everything going on, men occasionally lost their heads, which was even worst when it was an officer. Stephen Pontin from Mordialloc, Victoria tells the following harrowing story in his interview.

The beach we were on, I think it was a place called Navplion, and we got to […] this little beach and there was already hundreds and hundreds of troops there, British troops. And this colonel, a full colonel with all the red tabs, he was a staff officer from some headquarters of some sort, walkin’ up and down the beach tellin’ us what to do and what not to do, and he had all these troops, English troops with their rifles slung, tin hats on, and packs on their back.

And about three-o’clock in the mornin’ someone says, “There’s a boat,” and guess who was first into the water? The bloody British colonel with all the red bloody tabs on and all his troops followed him, all with their packs on, rifles slung, wadin’ out, and there was a sand bar and when they waded out about ten-yards they went down about fifteen-feet a water, then it come up to about a foot a water. That’s why the caiques [the boats] couldn’t come in.

They all drowned, you could hear ’em splutterin’, it was just every man for himself. All I had was a tin hat and I put me cigarettes under me tin hat, I was wadin’ out and I went down into it, off went the tin hat because the cigarettes were buggered anyway, full a sea water, and I swam out to the caique and they pulled me on board, there was about fifteen of us on it, takin’ us out to this silhouette, you could see a destroyer, just a silhouette in the dark, could just make it out. And guess what, it was the HMAS Vendetta, an Aussie destroyer.

Stephen Pontin

Unsurprisingly, Mr. Pontin becomes upset as he tells this story, and the tape is shut down temporarily.

Catching a breath in Crete

With most of the troops from Greece in Crete, the second stage of the evacuation could start, though it’s not like anybody got a chance to catch their breath. Before they knew it, Allied troops were facing the biggest parachute assault in history as thousands of Fallschirmjäger came dropping out of the sky.

German air superiority didn’t just allow them to drop soldiers onto Crete, it also badly hampered the evacuation efforts as the Luftwaffe and the Italian air force attacked any ship they could find. According to Mr. Bridges: “[…] the main losses weren’t from Greece to Crete, they were from Crete to Alexandria, the main ship losses. Once again because […] the Germans had airfields in Greece. and they had airfields in Crete.”

When asked whether air cover would have helped, Mr. Bridges answers confidently: “Well, oh, the whole thing would have changed. We wouldn’t have lost half as many ships if we had had air cover. Because that was our weakest point. We had nothing, not a thing at all. Not any aircraft at all. And see they had supremacy of the skies. They had everything in their favour.”

Suda Bay

Because of the speed and ferocity of the attack, coupled with the fact that the Germans seemed to be everywhere, the evacuation from Crete was pretty hectic. At first, ships were able to make it to the northern part of the island, moving men from there, while other troops made their way over the island’s central mountain range to make it to beaches in the south.

Maxwell Middleton from Western Australia was one sailor aboard a ship tasked to get men from Suda Bay, on the north-eastern corner of the island.

All I can remember of Suda Bay was the stench of burning oil mixed with the smell of, I don’t know burnt flesh or anything that it was. It seemed to be an unending stench because the whole thing was in a big bowl and some how the stench hung. But I can’t really recall other than the fact that we just seemed to be having an unending number of guys coming on board until we were no longer stable; if we had any more and we sailed quite often completely unstable […]I don’t know it just was a bit of a tangle.

Maxwell Middleton

As with Mr. Bridges in Greece, the ships being so crowded created its own issues:

[…] because the mess deck was crowded out, completely crammed full of troops so and food was just handed round whatever you could and so you didn’t worry too much […] If you did walk around to go to the heads (toilets) or something, say, you walked on bodies and being Australians they weren’t backward in telling you what they thought of you.

Maxwell Middleton

When asked what feeling he had when thinking back on his experiences during the evacuation, Mr. Middleton had the following to say:

Well, I think the feeling of letting them down and that you couldn’t get enough of them it. It was a concern to us that you know there’s all our guys and we can’t help them. We can only go so far. And we had to leave so many behind and it was that feeling that we’d let them. We couldn’t have done any more than we did I guess. But it’s still there. It always is.

Sfakia Bay

Sfakia Bay on the southern side of the island was another major extraction point. John Reid from Wahroonga, NSW was a sailor on the HMAS Napier, and was on several runs between Sfakia Bay in southern Crete and Alexandria.

We and Nizam and two other Javelin class Destroyers rendezvoused [at Sfakia Bay] at night and we picked up about I think about 600 or so the first night and headed all of us straight back to Alexandria. And there was naturally a lot of bombings from the Stukas and Junkers ‘88’s based in Crete to stop us getting back to Alex so there were lots of near misses. […] Then we had a just a very short time period there and we went back again for a second load and I think we took about 850 the next time. We got a very near miss. The second time we went up we started off as four but two of them were attacked on the way up and they had to return to Alex, so just Nizam and ourselves went on.

We arrived [at Sfakia] at about probably around about midnight, and we wanted to be in and away from there as quickly as possible. […] we just come in very very slowly and silently and everything was muffled, no talking.

John Reid

Mr. Reid’s captain and the local army officers then arranged to ferry the men from the beach, getting about 680 men aboard ship in just a few hours, then high-tailing it to Alexandria before light came and with it the dive bombers. With that done, Mr. Reid proudly explains that they did a similar run the very next night, claiming they were able to get another 800 to 900 men aboard.

Paul Cullen, an army officer from Sydney, was at Sfakia Bay on that final night and claims to be the very last to leave. In his words:

We had a little skirmish and killed a few Germans that were approaching the Sfakia evacuation beach. Any rate, the last night of the evacuation came, and we were told we would be the last […] to be evacuated by the destroyers, Australian destroyers, Nizam and Napier. So we got everybody off except ourselves, and the last little landing craft from Nizam arrived at the beach, and so I put everybody on board, and my batman, Legge, and I were the last two men on board.

And then, the little landing craft couldn’t get off the beach. So the midshipman in charge yelled out, “Last two men get off and push.” So with a sinking heart, in despair, I might mention, I got off and said “Come on Legge.” And he said, “Not f-ing likely.” So I got off and, there was a little wavelet, and I pushed, so that the landing craft went off. And if you’ve ever experienced despair, I was in despair. But Legge, always ready, threw me a rope, so I was hauled off in the sea, the last man officially evacuated from Crete.

Paul Cullen

Though he may have been the last man evacuated from Crete, sadly many men were forced to stay. Most were captured by the Axis and sent to be prisoners of war, while a handful managed to avoid detection. They often helped the Cretan resistance as they fought a brutal guerilla war against the invader.

Podcasts about Australians in the Mediterranean during WWII

Articles you may also like

Weekly History Quiz No.267

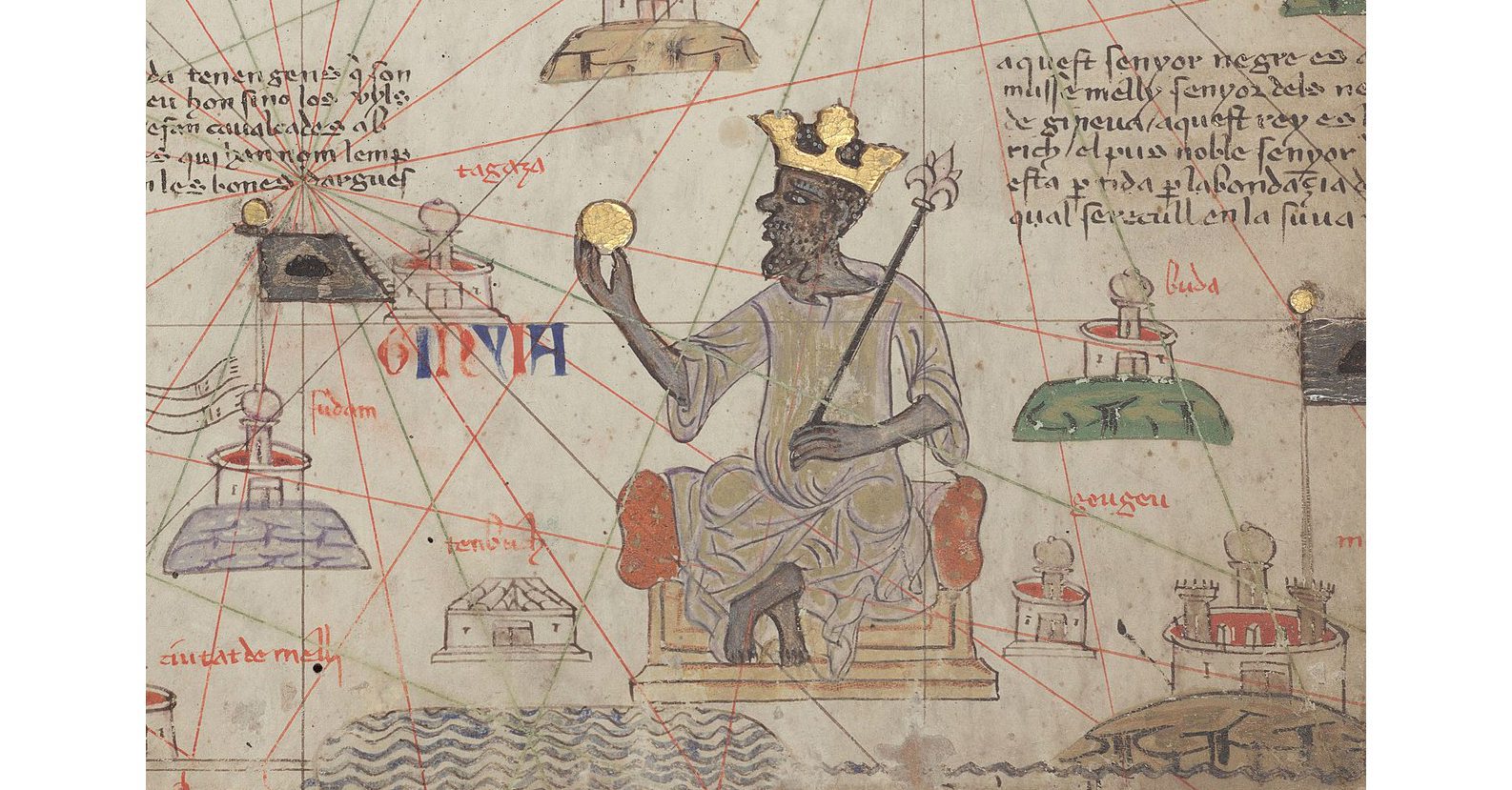

1. In the 1300s, which Empire produced approximately half the world’s gold?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

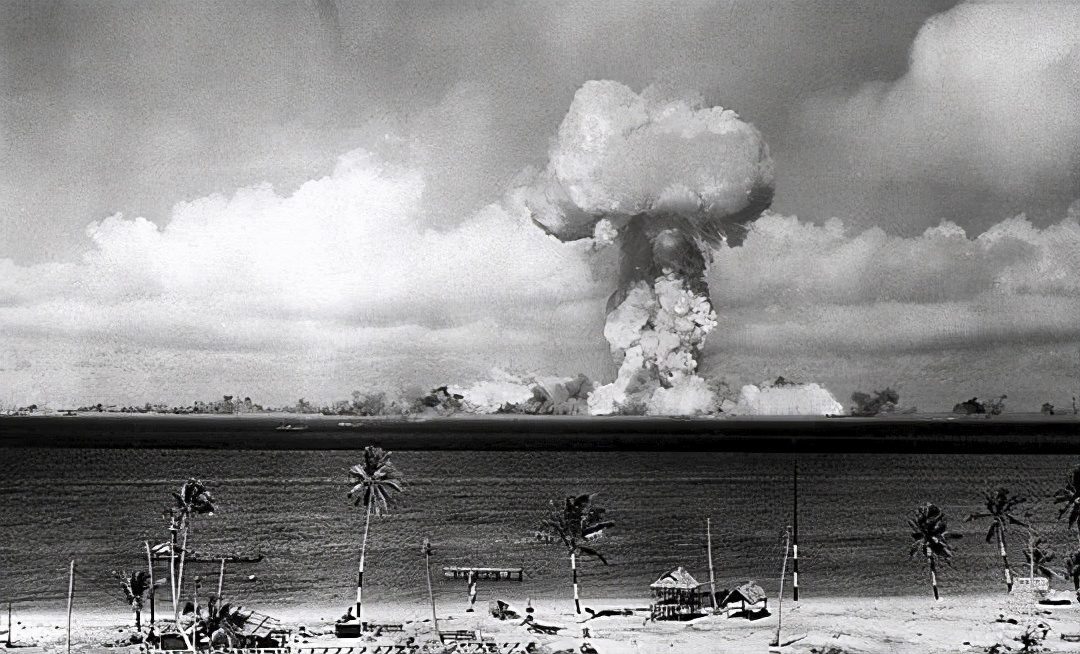

315 nuclear bombs and ongoing suffering: the shameful history of nuclear testing in Australia and the Pacific

Reading time: 6 minutes

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons received its 50th ratification on October 24, and will therefore come into force in January 2021. A historic development, this new international law will ban the possession, development, testing, use and threat of use of nuclear weapons.

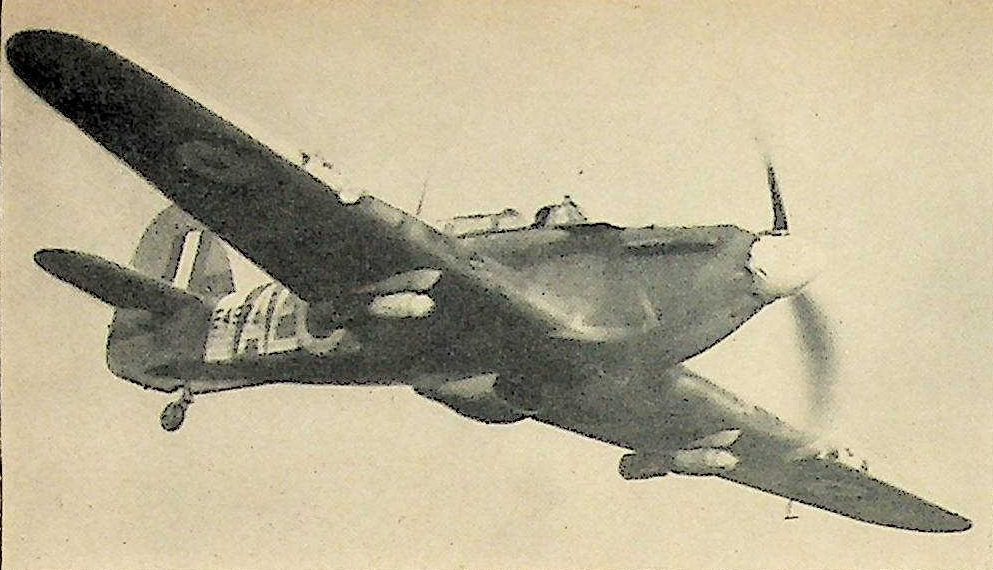

WWII Aircraft Recognition Quiz – General

10 randomly selected WWII aircraft each time you take the quiz.

Try again when you are finished for a new selection of aircraft!

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.