Reading time: 7 minutes

A major holy land for three of the world’s largest, most influential religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the area of the levant has long been hotly contested.

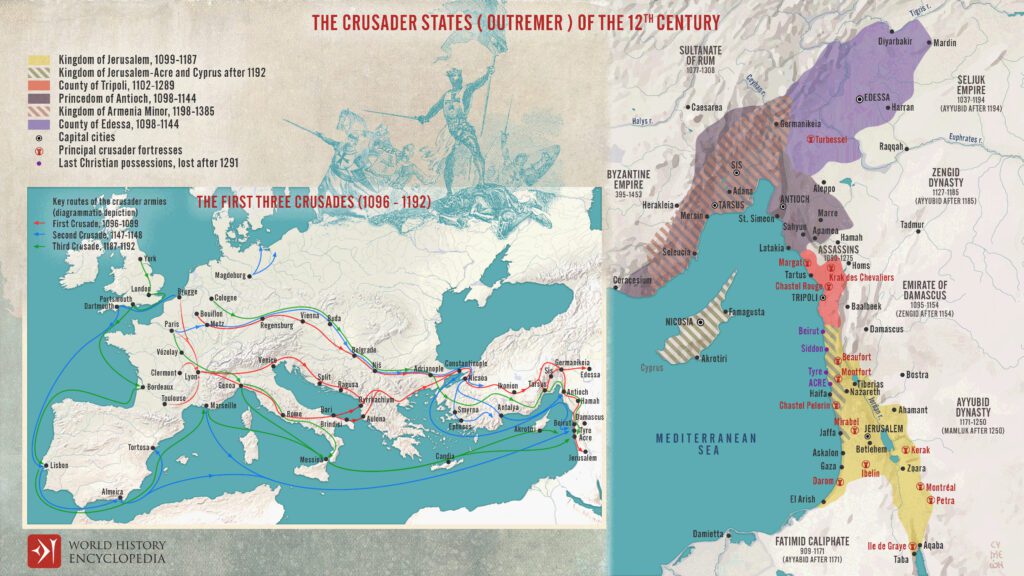

After several centuries of ownership and Christian domination under the Roman Empire and later the Byzantine Empire, the holy land of Jerusalem and the surrounding area fell into the hands of the Muslims in 969 under the Fatimids, and later the Seljuq Turks.

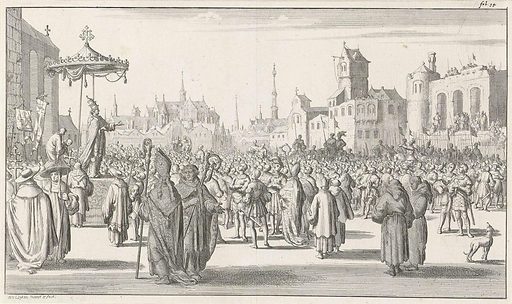

A huge threat to the waning Byzantine Empire, its leader Alexios I Komnenos requested aid from the European Christian world, and the Christian world answered. First with an unruly, disorganised “People’s Crusade”, and then by an official call for Crusade from Pope Urban II in 1095.

A long walk to the holy land and several years later, Jerusalem had been captured by the Crusaders in 1099, alongside many other cities across the region along the way. The crusades had been initially successful, and the holy land had been recaptured.

Now what?

This is where the four major crusader states were born: the County of Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, the County of Tripoli, and the Kingdom of Jerusalem. These states not only served as bastions of Western European influence in the Levant but also became focal points of intricate political dynamics, involving interactions with each other and neighbouring Muslim and Orthodox Christian powers.

How Were the Crusader States Formed?

Two of the specific crusader states that were formed found their origins in the path of the First Crusade. In 1098, during the siege of Antioch, the Crusaders led by Bohemond of Taranto and Raymond IV of Toulouse captured the city, laying the foundation for the Principality of Antioch.

Similarly, during the same year, the capture of Edessa by Baldwin of Boulogne led to the establishment of the County of Edessa. These initial conquests were marked by a combination of military prowess, opportunism, and alliances with local Christian and Muslim factions.

Of course, the crowning achievement of the First Crusade was the capture of Jerusalem in 1099, leading to the establishment of the Kingdom of Jerusalem under Godfrey of Bouillon, initially garrisoned with around 300 knights and 2,000 infantry. Meanwhile, the County of Tripoli was founded a few years later in 1102 by Raymond IV of Toulouse after the successful siege of the city of Tripoli.

These new crusader states were characterised by a feudal system, with European nobility ruling over a predominantly native population, and the Latin Church playing a significant role in governance and administration.

They were also marred by a myriad of new challenges. European nobles had travelled the length of the continent to execute a holy crusade and now found themselves in a new territory with new players and new subjects.

How Did the Crusader States Interact With Each Other?

Each new polity faced unique challenges. The first to be created, the county of Odessa, was mostly native Armenian – many of which were already Christian, making marriages into the existing peoples a relatively simple affair. Meanwhile, the principality of Antioch quickly saw the new rulers marry into the Byzantine royal line, allying themselves clearly with the Byzantine Empire.

Despite sharing a common goal of maintaining Christian control over the Holy Land, rivalries between the states were common. The Principality of Antioch and the County of Edessa frequently vied for territory and influence in northern Syria, leading to intermittent conflicts and shifting alliances.

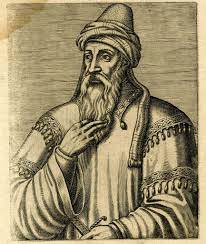

The Kingdom of Jerusalem, situated in the heart of the Levant, often acted as a mediator or arbiter in disputes between its neighbouring states. However, it too was embroiled in conflicts, particularly with the powerful Muslim states such as the Fatimid Caliphate and later the Ayyubid Sultanate under Saladin. The County of Tripoli, while geographically separated from the other states, played a crucial role as a buffer zone against Muslim incursions from the north.

Interactions with Neighbouring Muslim and Orthodox Christian Powers

The Crusader States existed in a volatile geopolitical landscape, surrounded by powerful Muslim states such as the Seljuk Sultanate, the Fatimid Caliphate, and later the Ayyubid Sultanate, all successors of the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates.

Diplomatic relations with these neighbours ranged from uneasy truces to outright warfare, depending on the balance of power and strategic interests.

Despite sharing a common religious faith, tensions often arose between the Crusader States and the Byzantines over territorial disputes and conflicting political agendas. Aside from the famous Fourth Crusade, which resulted in the sack of Constantinople in 1204, the crusader states consistently squabbled between themselves over leadership in the region, as well as with surrounding Christian nations.

In 1256, a rivalry between Venice (backed by the Knights Hospitaller) and Genoa (supported by the Knights Templar) sparked the War of Saint Sabas, a civil conflict over control of Jerusalem, lasting until 1270, significantly weakening the Crusader states and rendering them vulnerable to unified Muslim attacks.

Later, in 1268, King Conradin of Jerusalem was slain by Sicilian King Charles I of Anjou following the Battle of Tagliacozzo, and much later in 1277 a significant leader of the region in Hugh III of Cyprus (favoured by the Barons) was blocked from accessing the region by Maria of Antioch because they supported a rival leader – Charles I of Anjou.

This political manoeuvring led directly to Jerusalem being left without a resident monarch.

A Flash in A Pan: How Did These Alliances Change Over Time?

The political landscape of the Crusader States was characterised by ever-shifting alliances and conflicts. The Second Crusade (1147–1149) and the Third Crusade (1189–1192) saw European powers intervening in the Levant to support their brethren and protect their interests in the Holy Land, sometimes in unity against Muslim powers, but sometimes in contradiction to opposing Christian interests.

Internal divisions and external pressures gradually weakened the Crusader States over time. The loss of Edessa to the Seljuk Turks in 1144 was the first domino, and was a core driver in the launching of the Second Crusade, yet political division between the crusader states continued.

The eventual fall of Jerusalem to Saladin in 1187 dealt a severe blow to Latin Christian control in the region. Despite periodic attempts to reclaim lost territories through the subsequent Third and Fourth Crusades, with no unity, no ability to raise resources, along with waning and conflicting support from continental Europe, the Crusader States gradually succumbed to the rising power of Muslim dynasties.

Split into four major kingdoms, the Latin Christian Crusader States of the Levant played a significant role in shaping the political landscape of the Eastern Mediterranean during the medieval period.

Almost immediately facing squabbles for power, and very occasionally bubbling over into direct conflict between the states, the Crusader States constantly shifted in their level of regional power and struggled to unify behind one figure or group to face the threat of the neighbouring Muslim powers. For more on the Crusades, check out this Audiobook by George William Cox.

Podcasts about The Crusader States

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 160

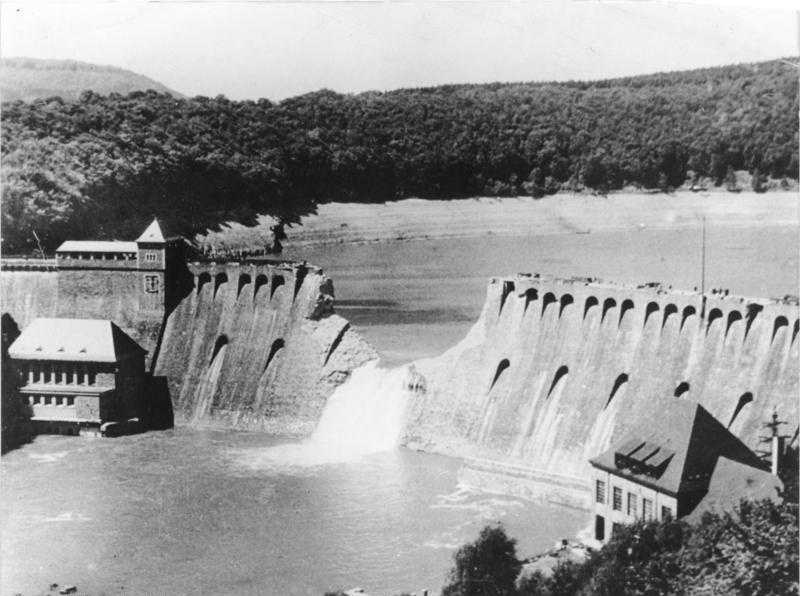

1. What was the code name for the WW2 ‘Dambuster raid’?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

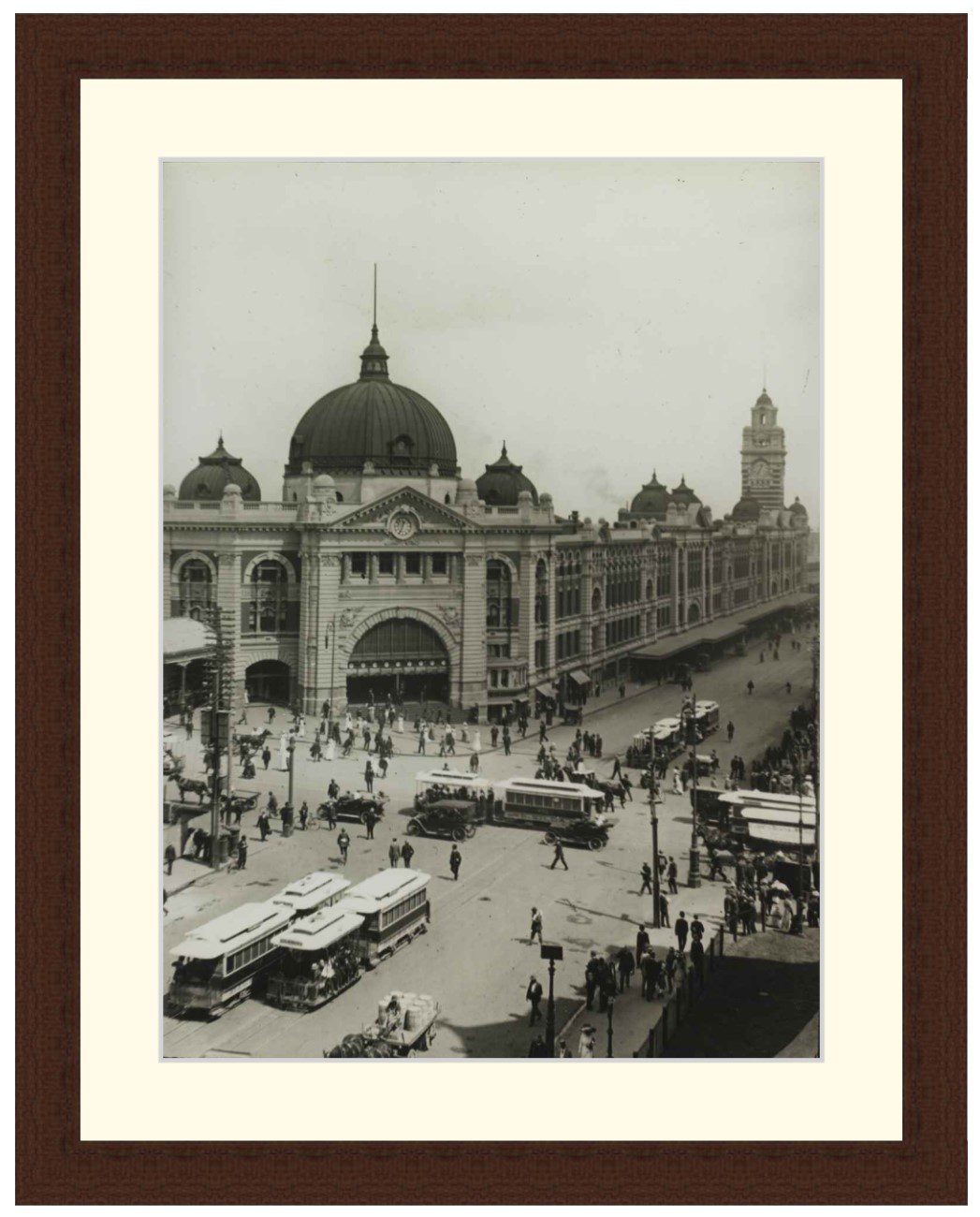

The Scrap Iron Flotilla – Australian Destroyers in the Mediterranean – Video

Anyone looking at the old, small and slow destroyer group would think the same. Soon, however, the Axis and the rest of the world would learn just how formidable it was. The ‘Scrap Iron Flotilla’ and those who manned it proved just how much grit, determination and valour can achieve.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.