Reading time: 8 minutes

Today (August 5) marks the 81st anniversary of Australia’s largest prison escape: the Cowra breakout, in New South Wales, during the second world war. In fact, it is one of the largest prison escapes in world history, but unless you are a keen war historian you may have never heard about it.

A small farming community was forever changed in 1944, when the sound of a bugle cut through the crisp night air at the Cowra Prisoner of War camp.

By Rebecca Hausler, University of Queensland

Shortly before 2am, hundreds of Japanese prisoners of B Camp ran towards the barbed wire fences brandishing makeshift weapons such as sharpened table knives and clubs.

Rushing through a hail of bullets fired by the Australian guards, hundreds of prisoners escaped into the countryside. In the following days, 334 prisoners were recaptured.

Four Australian soldiers and at least 231 Japanese prisoners were killed, while a further 108 prisoners and three guards were wounded. No civilian casualties or injuries were recorded.

As the dust settled, many would question why the prisoners would attempt such a bold and ultimately lethal escape plan. How do we as a society make sense of such bloodshed?

From non-fiction to fiction

While there have been a number of non-fiction works written on this event by authors such as Hugh Clarke, Charlotte Carr-Gregg, and Harry Gordon, it is works of fiction that have sought to fill in the gaps of history. They give us a way of understanding the incomprehensible.

The first author to do so was Australian poet and novelist Kenneth Seaforth Mackenzie. Mackenzie was stationed at Cowra during WWII and was on duty the night of the breakout.

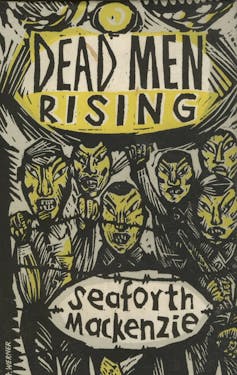

His novel Dead Men Rising was based on his experiences. Because of this, the book was initially halted from Australian release due to the publisher’s fears of libel claims.

The book was released in the UK and USA in 1951 but Australian readers had to wait until 1969, several years after Mackenzie’s death, to read his interpretation of the event.

Dead Men Rising is largely focused on camp life through the eyes of the guards in the lead up to the break out. There is little interaction with the Japanese inmates who are represented as “un-human”, “animal-like” and “unpredictable”.

Mackenzie depicts them as utterly foreign and incomprehensible to the Australian soldiers. This narrative likely reflects attitudes at the time with anti-Japanese sentiment still high in the early post-war years.

A Japanese perspective

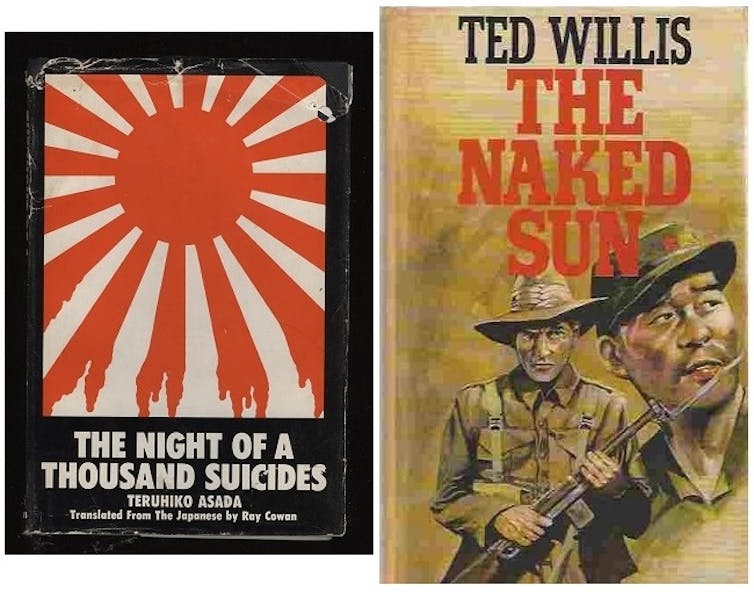

Several years later, Japanese author and former military doctor Teruhiko Asada, wrote Hiroku Kaura no Bōdō a title that translates as “The Secret Record of the Cowra Riot” in 1967.

It was received eagerly by English speaking audiences when it was translated by former Australian soldier and interpreter Ray Cowan in 1970 under the sensationalist title The Night of a Thousand Suicides.

Presented as a first-person narrative, the story had an intimate feel lacking in previous accounts, which led to some claiming the book was more fact than fiction, no doubt reinforced by Cowan’s inclusion of photographs from the Australian War Memorial. But this attribution is problematic given Asada was never imprisoned at Cowra.

The breakout was again revisited by authors in the 1980s. The Naked Sun, published in 1980 by British author Lord Ted Willis, uses a split narrative.

Alternating between an Australian and a Japanese perspective of the war, this novel highlights the unlikely similarities shared between the story’s two opposing protagonists, an ex-farmer from occupied New Guinea and an imprisoned Japanese Sergeant.

Childhood memories

Later that decade, British-Australian author Jim Anderson (of OZ Magazine fame) draws on his own memories of the Cowra breakout as a child in his 1989 novel Billarooby.

The coming of age novel depicts a young boy who seeks to help the “samurai” escape from the POW camp, amid a backdrop of familial trauma and the hardships of rural life.

The boy’s innocence highlights the inherent racism, bigotry and violence that permeate the town’s pleasant façade, disrupting the notion that the “enemies” are the ones behind the barbed wire fence.

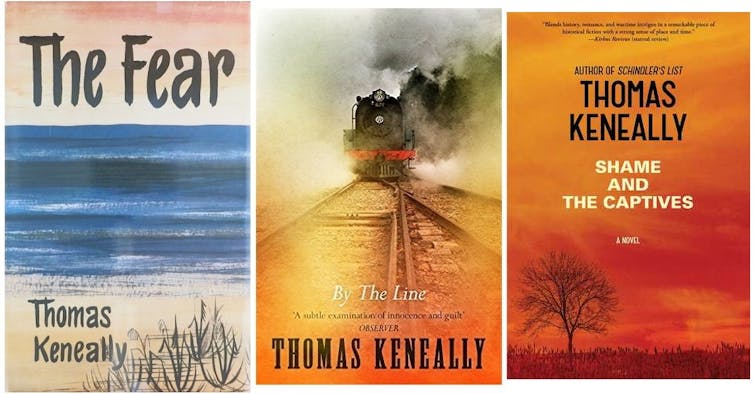

In 1989 Thomas Keneally revised and republished his 1965 novel The Fear.

The 1965 edition drew upon his boyhood memories of the breakout with this work briefly depicting the camp and subsequent breakout in the latter half of the book.

But in the revised 1989 edition, which was renamed By the Line, he omits any mention of the camp entirely. The author later said this early depiction was largely inaccurate.

With this fresh perspective, Keneally returned again to the breakout in 2013 with Shame and the Captives which is set in the town of Gawell, a fictionalised version of Cowra.

Keneally said in his introduction that now, rather than drawing on his faulty memories of childhood, he spent considerable time researching the historical event which informs his work.

By aiming to create a “a truth in this fiction” Keneally hoped to “interpret the phenomenon of Cowra”. His reimagining included explorations of Italian and Korean POWs who were also held at Cowra, but whose stories are often overlooked.

The most recent work which revisits the breakout is by Wiradjuri author Anita Heiss.

Her 2016 work Barbed Wire and Cherry Blossoms provides an Indigenous voice to the history of Cowra, a voice that has often been silenced in accounts of Australian history.

Issues of race, discrimination and loyalty take on a new sense of urgency in this wartime setting, yet also highlight that while much has changed in the last 75 years, so much has stayed the same.

Heiss echoed this view when she asserted there “are lessons still to be learned from the history of Cowra”, lamenting the regression in Australia’s treatment of detainees in centres such as Manus Island or Don Dale.

Cowra today

From this bloody chapter of history, the township of Cowra – today, a four hour drive inland from Sydney – has moved forward to promote itself as a beacon of peace, friendship, and understanding.

In a show of respect for the dead, the Cowra RSL Sub-branch cared for the Japanese burial ground informally until eventually the graves were relocated to what is now the Cowra Japanese War Cemetery, which opened in 1964.

In 1979 the Cowra Japanese Garden and Cultural Centre opened, and is considered to be a “tangible monument to peace and reconciliation”.

The gardens and the cemetery were symbolically linked by an avenue of cherry blossoms in 1988, and in 1992 Cowra was awarded further recognition to its peace efforts with The Australian World Peace Bell.

Festivals such as the Sakura Matsuri festival and the Festival of International Understanding further showcase Cowra as a “unique place … of reconciliation”.

This article was originally published by The Conversation.

Podcasts about the Cowra Breakout:

Articles you may also like:

Fake news was a thing long before Donald Trump — just ask the ancient Greeks

Reading time: 5 minutes

Thucydides and Plato lived through the crisis of Athenian democracy and, not unlike Trump, informed posterity that the fate of their beloved Athens resulted from the systematic misinformation and mis-education of the citizens.

Shipwrecks of the Manila Galleons

Reading time: 8 minutes

Huge ships filled with canons, gold, porcelain, silk, and other riches from Asia, the Manila Galleons were the key vessels in transporting rare goods from Asia across the Pacific Ocean to Spanish holdings in Mexico. From there, the cargo could easily be sailed across the Atlantic to Spain and Europe.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.