Reading time: 6 minutes

Once the centre of Nazi ideology and power, the German capital of Berlin was extremely important not only in the Allies quest to defeat Hitler, but in the rebuilding of Europe after War’s end. And yet while the Allies were indeed united in their collective opposition to the Third Reich, their similarities ended there, especially when it came to the Soviet Union.

By Michael Vecchio

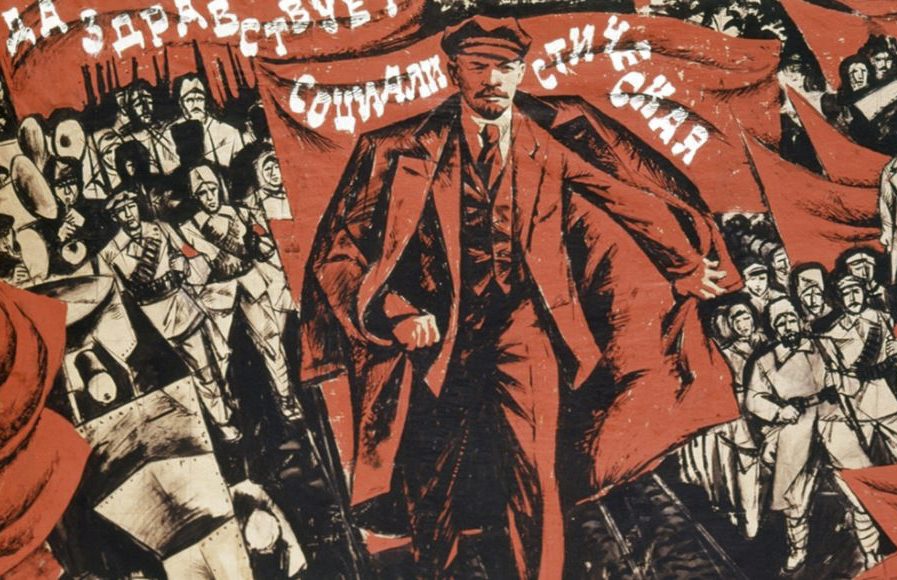

Joseph Stalin’s USSR had only joined the Allied war effort after a surprise invasion by the Wehrmacht, effectively trampling on the non-aggression pact signed with Hitler; and so with the eventual fall of Berlin, the Red Army (who had lost a catastrophic amount of life) was more than eager to continue the humiliation of Germany and cement the expansion of its Communist dominion.

READ MORE: The Soviet Role in World War II

This desire to further subjugate Germany and parts of Eastern Europe put Stalin directly at odds with the other Western Allies, whose desires for a post-War Europe included democracy and a free market. Yet the Soviet Union knew two things for certain: there was little appetite for further aggression, and the Red Army had played a significant role in ending the War. With this knowledge Stalin was fairly confident he had sufficient leverage to enact his vision of reconstruction, even if it was totally contrary to the view of the other victors.

With this the Western Allies let much of Eastern Europe come under direct Soviet influence (forming what Winston Churchill would later name, the “Iron Curtain”). This sphere of influence would also include Germany, and despite the hesitations of France, the UK, and the US particularly, the nation was divided in two: East and West Germany.

Berlin did not escape this division, it too was sawed in half, despite the fact that the city as a whole was in communist East Germany; the Western portion of the city retained its ties to the democratic West, which somewhat undermined the new dictatorship in the Eastern half of the European continent.

The Cold War had officially begun, and the Berlin question had seemingly been settled, yet unease remained for both sides. In the ongoing battle of competing social and economic ideologies, the West and the USSR sought to constantly undercut each other, in a pattern that would define the next 45 years of world history. But the first real test of post World War Two peace came in 1948, and naturally Berlin was right in the middle of it all.

The Berlin Blockade and the subsequent airlift became the first major episode of the Cold War and although it lasted just under one year, (June 1948 to May 1949), set the stage for the kind of indirect confrontation that would characterize the Cold War period. Though the barriers of a divided Berlin had been set out, the Soviets felt increasingly insecure about their ability to control their sector and the people within it. In an effort to stunt the economic growth of West Berlin, the USSR blocked much of the Allies’ road, railway, and canal access. With the blockade in place, suddenly some 2.5 million Berliners had little to no access to quality food, medicine, electricity, and other basic commodities.

The beginning of the blockade was largely seen as a response to US President Harry Truman’s declaration of the “Truman Doctrine”, which called for international efforts to try and curb the spread of communism; if the West could not adequately support its rebuilding efforts, then surely communism would be seen as a superior economic model. Ironically, these heavy-handed tactics only served to embolden the perception of the Soviets and its satellite states as regressive regimes.

A few months before the Blockade began, the US Congress had passed the European Recovery Program, or the Marshall Plan, transferring nearly $13 billion to various economic recovery agencies in Europe; the Blockade now in force was a major obstacle not only for the Americans, but all Western Allies, who would go on to form NATO in the spring of 1949.

Almost immediately after the imposition of the blockade, the Allies began organizing an airlift to deliver basic goods and other supplies to the people of Berlin; over a period of 11 months British and American planes transported nearly 2.3 million tons of supplies (food, fuel, and other necessities) into West Berlin, with a peak daily delivery total of 12, 941 tons. Some 700 aircraft and over 270, 000 flights successfully delivered their cargo, with one plane reaching West Berlin every thirty seconds!

Though it was deemed unlikely to succeed, the airlift ultimately became a success story for the West, and by May 1949 it had become increasingly obvious that the Blockade had failed. On May 12, the USSR officially lifted the Blockade and reopened all roads, rails, and other transport routes into West Berlin, though the airlift would continue until September in case the Soviets reversed their decision.

READ MORE: Constructing Oppression: The Berlin Wall and the Literal Iron Curtain

Seventeen American and eight British aircraft had crashed during the airlift with a total of 101 fatalities; all in all the US Air Force had transported 1.7 million tonnes of material, with the Royal Air Force delivering of 541,000 tonnes.

By the end of it all on September 30, 1949, West and East Germany were officially formalized as separate nations with the divided Berlin still a point of contention; eventually the infamous Berlin Wall would be constructed to further limit the exodus of citizens from the communist regime in East Germany.

READ MORE: Berlin Airlift Facts and Figures

The partitioning of Germany and Berlin, and the subsequent Blockade and airlift indicated just how fragile the alliance between the Allies had been, and it signaled an era of uncertainly for millions around the world as the Cold War heated up.

Podcasts about the Berlin Airlift

Articles you may also like

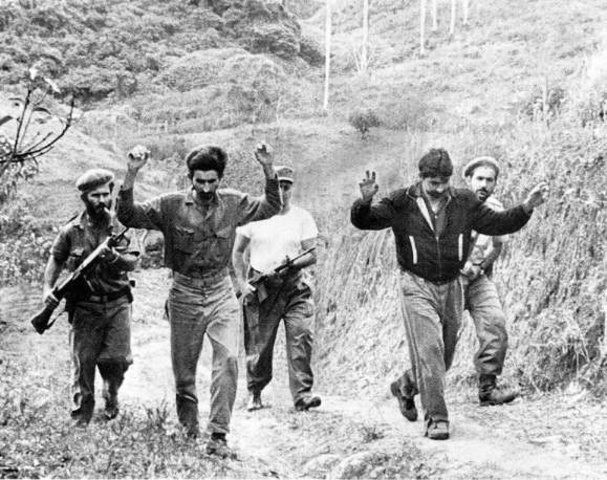

Hubris and Miscalculation: The failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion

HUBRIS AND MISCALCULATION: THE FAILURE OF THE BAY OF PIGS INVASION By Michael Vecchio The threat of Nazi villainy had been defeated, however another authoritarian threat rapidly placed over half of Europe behind what Winston Churchill called an “Iron Curtain”. The Soviet Union’s aggressive brand of Communism startled much of the Western world, but perhaps […]

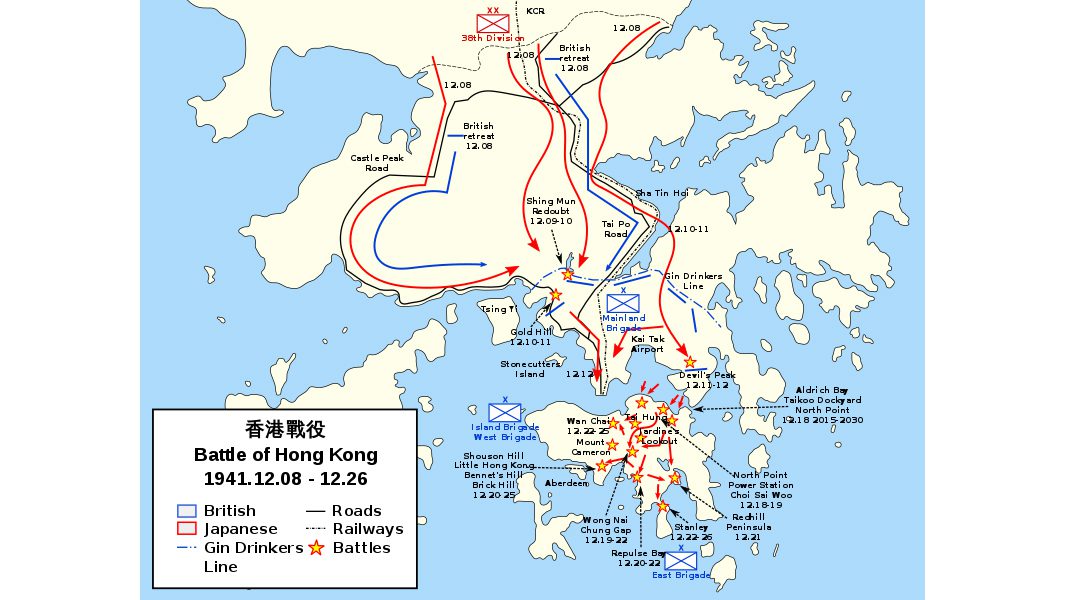

The Battle for Hong Kong – London’s Lost Cause?

Within 12 hours of Pearl Harbour being bombed by the Japanese at the outset of their entry to World War 2, they began their invasion of the British Territory of Hong Kong on the 7th December 1941. The British didn’t just roll over as is assumed but instead followed Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s command – […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.