THE BLACK WAR

Reading time: 10 minutes

In the heat of commemoration of Australians’ involvement in the first world war, it’s timely to remember their participation in the frontier wars in the 19th century. As Nicholas Clements, the author of a new book on the best known frontier war, the Black War in Tasmania in the 1820s, points out, the death rate among the colonists was half that of Australians in the first world war, much higher than the death rate in the second world war and the casualties affected almost every family in Tasmania.

The death rate among the Tasmanian Aborigines was even greater. Of the 1000 Aborigines in the war zone he estimates that more than 600 were killed by the colonists. These startling statistics alone would indicate that, along with the first world war, the Black War in Tasmania holds a significant place in Australian history

By Lyndall Ryan,University of Newcastle

The Black War debate

Yet a decade ago, Australian historians were locked in a furious debate, known as the history wars, about whether the Black War was actually a war at all. The antagonists included Henry Reynolds and me, who argued that the colonists had conducted a long and bloody guerrilla war with the Tasmanian Aborigines for possession of Tasmania.

That war reached a climax when the governor made a verbal treaty with a key Aboriginal chief, Mannalargenna, to vacate Tasmania for sanctuary on an island in Bass Strait in exchange for a fiduciary duty of care. In a ground breaking analysis of the treaty and its aftermath in 1995, Reynolds claimed that the Tasmanian government had failed to observe the spirit of the treaty and that the surviving Aboriginal population should make a case for reparation.

The protagonist, Keith Windschuttle, asserted that the Tasmanian Aborigines were politically incapable of conducting a guerrilla war against the settlers let alone to make a treaty, because they had no concept of land ownership. Rather, he argued that they were “black bushrangers” led by “educated black terrorists” disaffected from white society who simply attacked settlers’ huts for plunder.

He also asserted that historians like me had wildly exaggerated colonial massacres of Aborigines and that contrary to my estimate of four Aborigines killed for every colonist, he claimed that two colonists were killed for every Aborigine. Thus the Black War was not a contest for the possession of Tasmania, but rather the destructive work of violent terrorists on innocent colonists. The overall purpose of historians like Reynolds and me, he concluded, was to overturn the long held view that Australia was a nation with a peaceful past and replace it with a more shameful view that the Australian nation had been forged from the bloody violence of frontier wars.

After the History Wars

When the fog of the history wars lifted, the political terrain of the Black War had vastly changed. Rather than shutting it down, as Windchuttle had tried to do, he breathed new life into it.

Picking over the entrails, a new generation of Tasmanian historians such as James Boyce, Ian Macfarlane and Philip Tardif, concluded that Windschuttle had simply dismissed key evidence of well-known massacres because it did not suit his case. A few years later, James Boyce, in his award winning book, Van Diemen’s Land, presented a scathing assessment of the official archival sources of the war, the 19 volumes known as “The Depredations” which Windschuttle had more or less taken at face value.

The archive, Boyce asserted, was constructed as justification for Governor Arthur’s decision to proclaim martial law in November 1828 and thus operated as a screen to hide the fact that most Tasmanian Aborigines were already dead. Four years on, in my new book on the history of the Tasmanian Aborigines, I also agreed that most Aborigines were killed before martial law but that paradoxically more colonists, including women and children, were killed while it was in force.

How then does Clements’s book differ from these accounts?

Women and the Black War

Clements takes a bottom up view of the Black War. Rather than focusing on the policy makers in Hobart and London, as most historians have tended to do, he focuses on the war zone in the grasslands of eastern Tasmania and analyses the attitudes, experiences and tactics of the combatants. As the first historian to take this approach, he makes important new findings about the triggers for war and how once it was under way, the tactics changed to grapple with new circumstances.

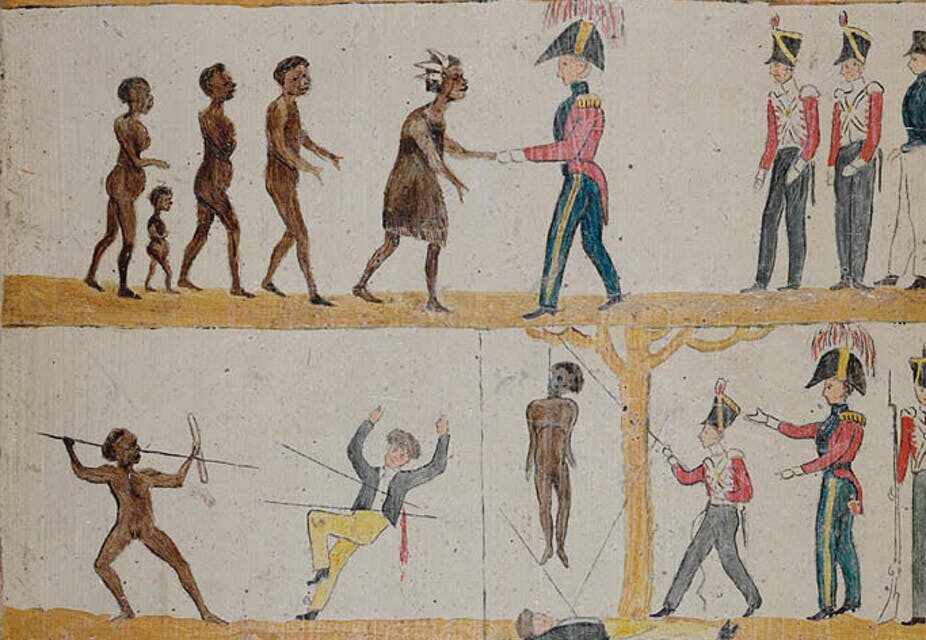

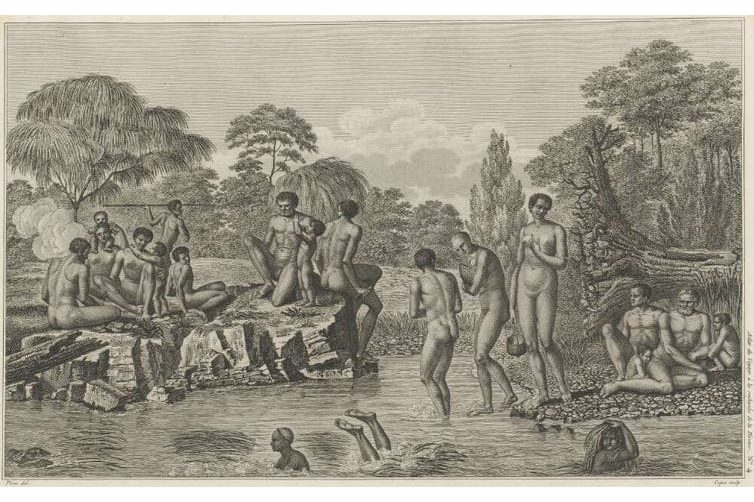

He considers there were two triggers for war. The first was the severe gender imbalance among the convict shepherds and stockkeepers in the 1820s. This issue has never been properly addressed before. Deprived of white women on the frontier he considers that the convict men began the practice known as “gin raiding”. That is, one or two of them ambushing an Aboriginal camp at night and abducting one or two women, taking them back to their hut, sexually abusing them for a week or so and then torturing and killing them.

In hindsight it seems extraordinary that the convict men believed that they could escape retribution. They must surely have known that Aboriginal men would quickly exact bloody revenge for the brutal treatment of the women by surrounding the culprits’ hut in daylight and then brutally clubbing them to death. From there the spiral of violence escalated.

To avenge the loss of their comrades, the stockkeepers and shepherds in the district would form a vigilante party and attack the Aboriginal camp at night and shoot as many Aborigines as they could. In turn the survivors would attack colonists’ huts for provisions. Clements considers that the vigilante parties “almost certainly took a greater toll on the Aboriginal population than the official pursuit parties” that were formed later in the war. Armed with Brown Bess muskets, they usually fired first and then rushed into Aboriginal camp and clubbed and bayonetted their victims.

“Gin raiding” according to Clements continued throughout the war and became one of its key characteristics. So it’s not surprising that more than 75% of the war’s 219 colonial casualties were single male convicts or ex-convicts aged between 16 and 35. One wonders if the war would have taken a different tack if the colonial authorities had put a stop to these dreadful acts and sought a more equitable gender balance among the convicts.

The sheep question

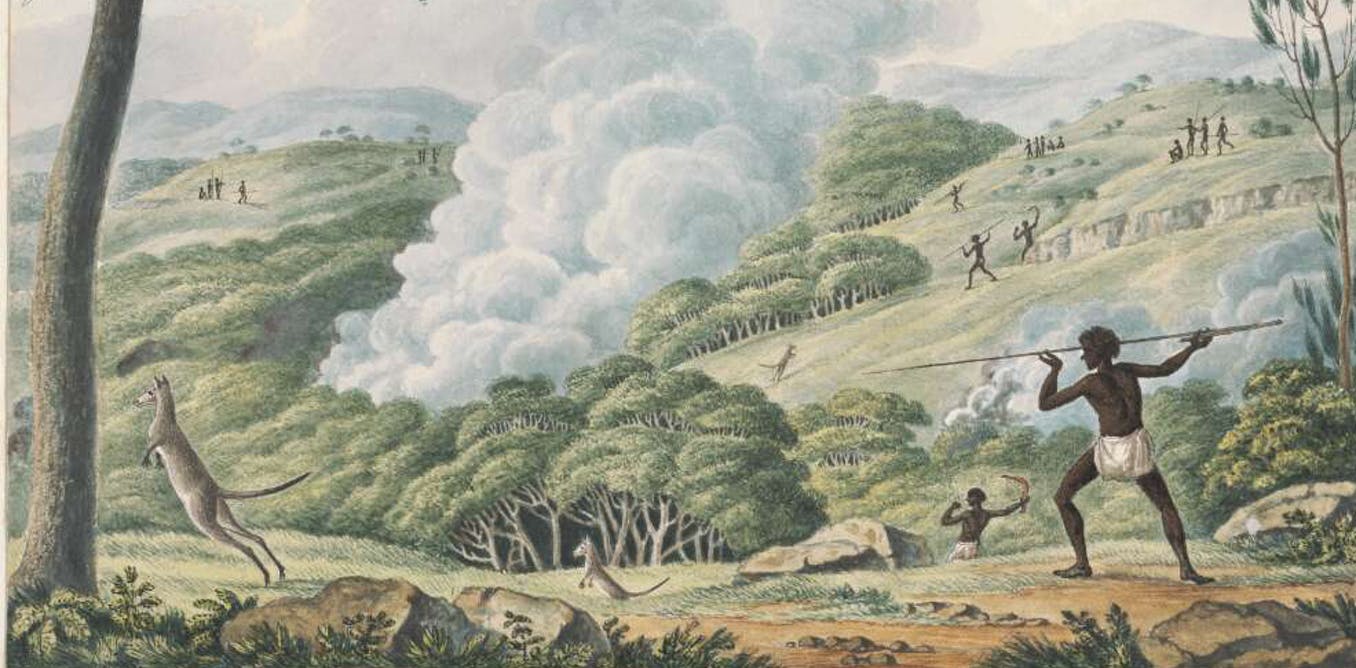

The second trigger, more widely accepted, was the ever increasing flocks of sheep that spread over the Aboriginal hunting grounds in eastern Tasmania in the early 1820s. The Aborigines, who did not eat mutton, were known to drive away the sheep, spear them and in some cases, break their legs so they were of no further use to the colonists.

Enraged by what they called vandalism, the colonists would call on the local magistrates to send out pursuit parties of up to ten armed men after the culprits. But rather than arresting them, the pursuit party would surround the nearest Aboriginal camp at night and “dispose” of them. Some colonial communities even had a “pre-arranged signal” to announce a pursuit and according to Clements, by 1829, response times were remarkably fast.

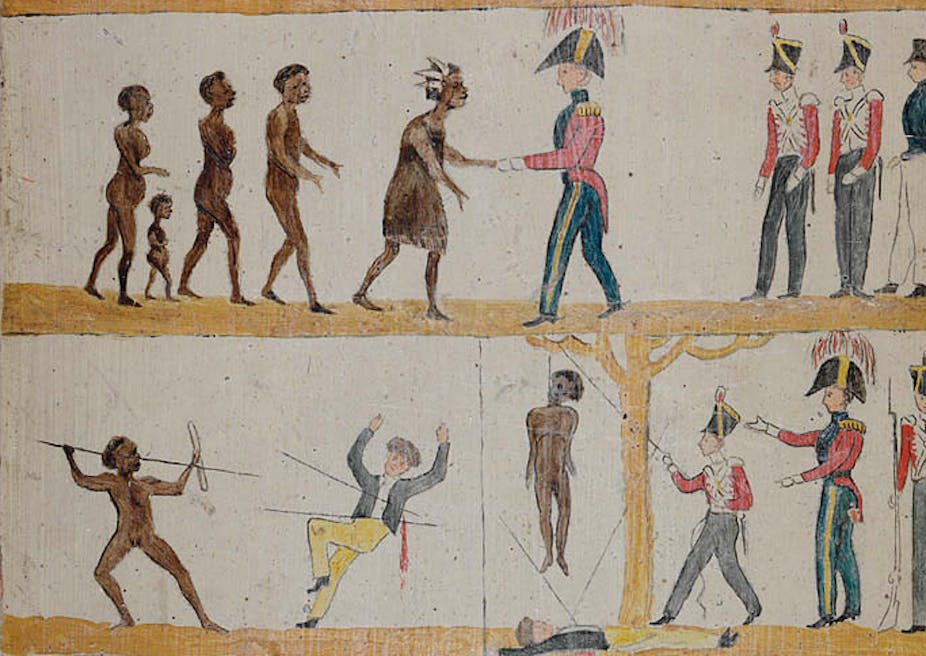

At the end of 1826, the colonial government formed military parties of between five and ten soldiers to patrol the war zone. They would rise before daylight to track down “native smoke” and then ambush the camp while the Aborigines were sleeping and shoot at them. After martial law was proclaimed in November 1828, nearly half the colony’s military force was out in patrol. The final group, were the “roving” parties, which were formed in the later stages of the war. Their orders were to secure the countryside for weeks at a time in the hope of “capturing and destroying the natives”. By 1829, the police magistrate in the centre of the war zone had fitted out seven civilian parties and four more were added the following year.

Clements is the first historian to place the pursuit parties into four separate categories and carefully analyse their tactics. Rather than failing in their objective, as many historians believe, he considers they were extremely effective. Their tactics dramatically reduced the Aboriginal population from an estimated 1,000 in the war zone in 1826, to fewer than 200 in early 1830.

Resistance

However, rather than surrender in 1830, as the colonists expected them to do, the Aborigines simply changed tactics to take advantage of the colonists’ weaknesses. They now secreted themselves in the hills and watched the colonists on their farms in the valleys, sometimes for days at a time and waited until the master went out, leaving those in the farmhouse vulnerable to attack. Then a group of five or six Aboriginal men would swoop down and carry off flour, potatoes and tea. Sometimes they would set fire to carts and buildings and at other times they would hack white women and children to death. The colonists, who were undermined by being constantly watched by the enemy and not knowing when and where they would strike next, lived in fear for their lives.

How successful were the Aboriginal resistance tactics? Clements is in no doubt that the Aborigines terrorised the colonists in the latter years of the war, but as they were fearful of the dark and the evil spirits who possessed it, they did not attack the colonists at night. Even so, the colonists frequently acknowledged the adroitness and effectiveness of the Aborigine’s guerrilla tactics and were always fearful they would be attacked at night. According to Clements, the Aborigines were a warrior culture which celebrated martial prowess – bravery, skill and honour were central to their lives.

Yet at the same time, the Aborigines were more or less constantly on the run from the various pursuit parties who were most effective at night. They were frequently forced to leave their elderly and sick relatives to follow behind and had to keep their night fires to a minimum so as not to attract their pursuers. By the later stages of the war their usual seasonal patterns of movement had been violently disrupted.

Nearly all of them bore scars from gunshot wounds inflicted by the various pursuit parties, were deeply traumatised by the night time attacks and were fearful of the redcoats. When they were reunited with lost relatives, Clements’ deeply affecting account of their tearful embraces and their devastation at the loss of other relatives stands out as the most powerful section in the book. As staunch patriots, they risked everything to fight for their country. When they finally surrendered fewer than 100 remained.

What conclusions does Clements draw from the Black War?

He is in no doubt that it was started by male colonists in search of sex and that it escalated into a long and bloody guerrilla war for the possession of the grasslands of eastern Tasmania. Had the Aborigines co-ordinated and sustained their resistance tactics, they would have increased the colonial casualties from the 400 or so that were recorded. In the end they were defeated by the increasing number of pursuit parties and the loss of more than 600 of their comrades.

Clements’ book presents the Black War as a horrifying and brutal guerrilla war of attrition. It not only led to the virtual extermination of the Tasmanian Aborigines, it also took many hundred colonial lives and impacted on every colonial family in Tasmania. Yet unlike the first world war, it is barely recognised today as a major event in Australian history. At a time when Australians are commemorating the great war which was fought overseas, Clements’ book is a timely reminder that a very significant war was also fought on Australian soil.

This article was originally published in The Conversation

Articles you may also be interested in

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.