THE BENGHAZI HANDICAP AND THE SIEGE OF TOBRUK

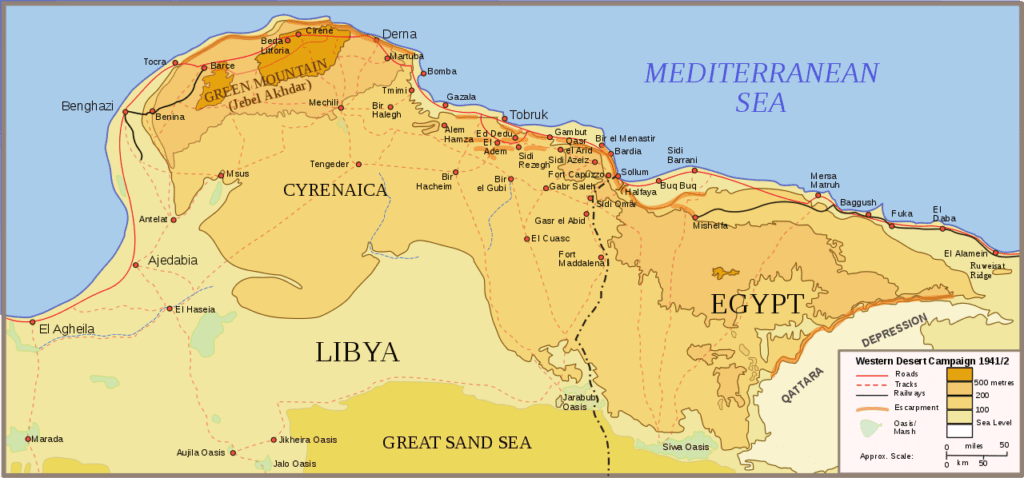

The Benghazi handicap is the name Australian soldiers gave to their race to stay ahead of the German Afrika Korps in Libya, 1941. They won the race, but the reward was just to be besieged in the city of Tobruk for 241 days, the longest siege in British military history. In this article, we use the words of veterans themselves to describe these events, and how the Rats of Tobruk experienced the siege.

By Fergus O’Sullivan

1941 began very well for the British and Australian forces. The Italians forces had invaded British-held Egypt from Libya late 1940, but the fascist offensive had collapsed at the merest fraction of resistance. Not only had the Allies been able to defend against it, they had been able to launch a successful counterattack.

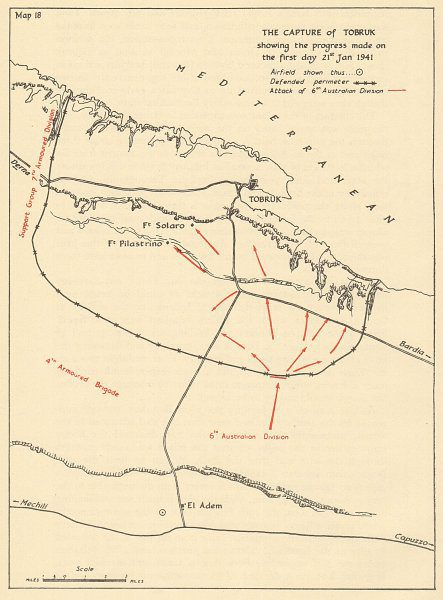

The Capture of Tobruk

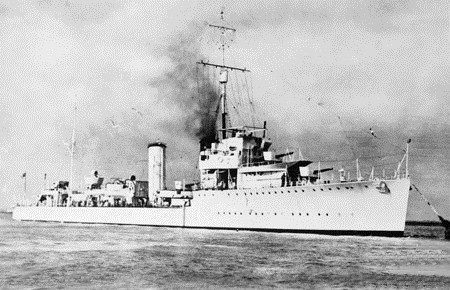

The first Libyan town of note taken by the British-Australian force was Bardia in January 1941, which we’ve covered at length in our article on the victory at Bardia. It also has the dubious honour of being the first Italian town shelled by the Royal Australian Navy, which we talk about in our article about the HMAS Sydney.

Soon after, the town of Tobruk and its strategic port also fell into Allied hands. Though the fighting had been fierce, it hadn’t lasted long and the defences of the town were mostly intact still when the town and its port were captured. This would prove to be a great boon later, when the British forces themselves would be besieged in Tobruk.

John Campbell from Mildura, Victoria was one of the people dropped off by ship just a few weeks after Tobruk had been taken. He recalls seeing burnt out vehicles everywhere, but that the town itself was mainly untouched.

One of the men who was able to poke around the town a little soon after it had been captured was Ray Norman from Sydney. He confirms that most buildings were undamaged. He also tells the story of finding a cash box full of lira notes in the abandoned Bank of Italy. He and his mates used the bundled notes as toilet paper or to light cooking fires, not finding out until later that the lira was still perfectly legal tender and they had burned and wiped their behinds on a small fortune!

To Benghazi

With Tobruk in the rearview mirror, the British and Commonwealth forces pressed on, taking several towns. The most important of these was Derna, another port. These towns mostly fell without incident, though there was sporadic fighting here and there between the Italians and the Allied forces.

Fortune seemed to smile on the Allied war effort, or at least it did until Benghazi. The town itself was taken without a fight, according to Alexander Barnett from Glenferrie, Victoria, who added that they found several Italian heavy guns in good working order that his unit made ready for their own use.

Because the campaign had been such a doddle, British commanders figured that the worst of the fighting must be over in North Africa. As such, they decided to send the larger part of their force, made up of mostly British soldiers, to Greece and Crete to prepare for the German invasion there. A force of mainly Australian troops would stay in Libya as a garrison in case the Italians decided to try their luck again

Though this made sense at the time, it ended up being a pretty serious mistake. Unbeknownst to the Allies at the time, Berlin had decided to help out its Italian allies and had sent Field Marshal Erwin Rommel and his Afrika Korps to North Africa. The Desert Fox would become a thorn in the Allied side for the next few years.

The Germans Arrive

The first anybody saw of the Germans was when Australian pioneers about fifty miles south of Benghazi noticed some planes flying over. According to one of them, Jack Bertram from Maldon, Victoria, he pointed out the aircraft and was told “they’re German, they’ve got a cross on them.” Soon after, the first reports came in that the Germans had landed in Tripoli, just a few hundred miles away.

The British forces were completely unprepared for the onslaught that Rommel was seemingly preparing, and the order quickly came down that all forces were to retreat back to Tripoli as it was the first town with decent defences.

Mr. Barnett recalls spiking his captured Italian guns, while Mr. Bertram was ordered to blow up a bridge over a gully he calls the Wadi Cuff. However, when his unit arrived they found the Italians had already blown it weeks before, so they made haste to turn back and join the retreat.

The Benghazi Handicap

The retreat to Tobruk wasn’t exactly Dunkirk levels of chaos, but it was made in great haste: the Australians knew that if they were caught before they reached Tobruk they’d be toast. The breakneck speeds at which they were going quickly gave it the nickname the “Benghazi handicap” after the type of horse race.

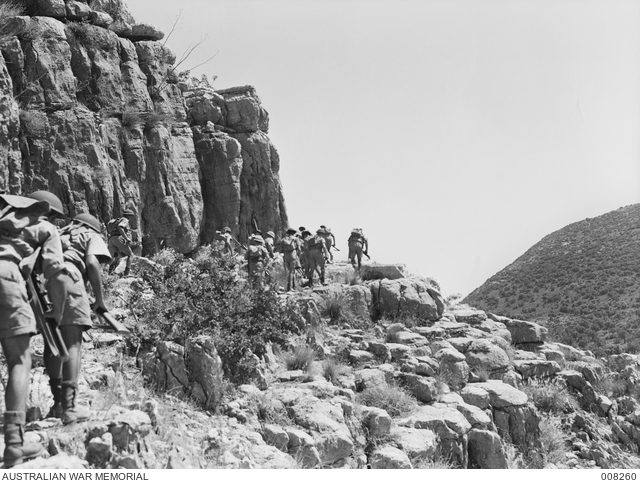

In the opinion of Mr. Barnett, the handicap didn’t really start until the troops had reached the desert south of Derna. Up to then, things had been going alright, but then a sandstorm hit the area one night, causing massive confusion. The chaos slowed down the column significantly, allowing the Germans to catch up.

One example of the chaos was the story of another Australian soldier, Raymond Widdows of Moonee Ponds, Victoria. He was part of a truck convoy meant to supply Benghazi and heard some of the fighting as his unit approached. When he reported it to an officer, he was told “that’s the Indian army on manoeuvres, don’t worry about that.” It wasn’t until the next day that they ran into a unit of Australian pioneers holding off the German vanguard that he realized what was really going on.

The Germans weren’t just behind the Australians, either: because the British had failed to take the high ground to the south of the coast thanks to the sandstorm near Derna, part of the Afrika Korps took that high ground and started to overtake the Australian forces. According to Rupert Goodman of Kew, Melbourne “you could see the Germans out there in the sand, kicking up the dust.”

Apparently, the Germans were able to move a few units ahead of the Australians and capture some command staff and ambulance personnel. Among them was Thomas Canning from South Australia, who reported that one of the generals captured didn’t believe what was going on until a German with a machine gun ordered him out of his car.

Things were looking up for the Germans, but the Australians had hurried enough that they made it to Tobruk before the Afrika Korps, even if only by a whisker. According to Mr. Goodman, the Germans were so confident in their success that a high-ranking German officer showed up at Tobruk in just a staff car, assuming the city had already been taken. He was quickly taken prisoner, a victim of his own hubris.

The Siege of Tobruk

Beating the Germans to Tobruk was only one part of the challenge, though, next was to survive the siege. The Germans had completely surrounded the city, but thanks to the excellent defences abandoned by the Italians, the Allies who were mostly Australian soldiers, but also British, Poles and Czechoslovak volunteers, were able to hold them off for the better part of eight months. The 9th Australian Division composed the majority of the allied garrison.

Still, though, it was a hard time. The Germans and their Italian allies would regularly bomb Tobruk — almost all the statements from veterans mention the Stuka dive bombers and the noise they made as they came down for a bombing run — as well as near constant raids and attacks by both infantry and tanks.

One infantryman, Charles Cutler, who would go on to become Deputy Premier of New South Wales, recalls that he would lie in his trench most of the day, exchanging fire with German units lying low in their own holes. According to him, it was the “closest to trench warfare” Australian units ever got in WWII.

Another soldier, Kenneth Clarke from Adelaide, mostly remembered the terrible food: most meals consisted just of biscuits and brackish water. In his words, “the only thing that kept us going was the ascorbic acid tablets, the vitamin C.”

To add insult to injury, the Germans would broadcast propaganda programs over the radio. Organized by the American fascist William Joyce, who went by the name Lord Haw-Haw, these were mostly nasty jibes aimed at the men surviving in the dust of Tobruk. In one of his harangues, he derisively named the defenders the Rats of Tobruk, a name which the Australians cheerfully appropriated and wore as a badge of honor.

It is hard to find a better description of the unique style of the Australian troops than that of one of the British soldiers who fought alongside them.

The Australians regarded themselves as the best fighters in the world. They were. This was not by dint of discipline, to which they were recalcitrant; they were held together by ‘mateship’, refusing to let each other down. Nor was it by organisation; their deficiencies in this respect were atoned for by initiative and reckless improvisation. At night patrolling they had no equals. The Fusiliers got on well with them and were accepted as honorary Australians, not starchy Brits or stuck-up Poms. Later, when we were in defensive positions on the ‘Blue Line’, an Australian unit we had for our neighbours used to lift mines to get the explosives out to go fishing. At night they would send out a foraging party to raid the DID, the big ration dump, where tins of goodies we rarely saw were stashed away. After one of these raids, they would always send some one across to give us a share.

Major John McManners, Royal Northumberland Fusiliers

The forces in Tobruk were supplied by the Tobruk Ferry Service, which was a force of Royal Navy and Royal Australian Navy warships that kept the defenders supplied and supported. These included vessels of the Australian ‘Scrap Iron Flotilla’ which made dozens of trips through the gauntlet of German and Italian air, submarine and surface attacks. This included the evacuation of the majority of the 9th Australian Division and their replacement with the British 70th Division. After 198 days under siege the men of the 9th Division were exhausted. They had suffered 3,164 casualties including 650 killed, 1,597 wounded and 917 captured. Their tireless work improving the defences of Tobruk as well as their aggressive raiding of the German and Italian positions were vital to the success of the defence.

In the end, though, the Rats were a lot tougher than the Germans: after 241 days Rommel had run out of ideas and the clock was ticking on the British counter offensive. Seeing no other solution, the Desert Fox retreated back to Libya to rest and regroup. Breathing a sigh of relief, the Rats of Tobruk got some rest themselves, but not for long as the next chapter in the desert war loomed.

This project commemorating the service by Victorians in the Mediterranean theatre of WW2 was supported by the Victorian Government and the Victorian Veterans Council. Sign up to the newsletter at the bottom of the page to be notified when the next article in this project is released.

Articles you may also like

Australia’s war with France: The Campaign in Syria and Lebanon, 1941 – Podcast

AUSTRALIA’S WAR WITH FRANCE: THE CAMPAIGN IN SYRIA AND LEBANON, 1941 – PODCAST Operation Exporter was a little known, but very important campaign for the Australian military. It involved Australian’s fighting a strange war against confused Frenchmen who were not supposed to be our enemy. France had been defeated and subjugated by the Germans. The […]

Remembering the Victory at Bardia

Just over 80 years ago, Australian forces fought their first major battle of World War II. Bardia, a small town on the coast of Libya, some 30 km from the Egyptian border, was an Italian stronghold. The Australian troops occupied Bardia, defeating the Italians in a little over 3 days. Australian veteran, Phillip Wortham, simply […]

Scrap Iron Flotilla: The Royal Australian Navy at its Best

To the Axis Powers, the Australian flotilla that fought in the Mediterranean during the Second World War appeared to be no threat. Anyone looking at the old, small and slow destroyer group would think the same. Soon, however, the Axis and the rest of the world would learn just how formidable it was. The ‘Scrap […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.