THE BATTLE OF GREECE – AUSTRALIA’S TEXTBOOK REAR-GUARD ACTION

Reading time: 13 minutes

Retreat doesn’t always mean defeat, sometimes it can be a victory to withdraw in good order and deny your enemy a total victory. This is was the outcome for the allied forces in Greece during April 1941, thanks in part to textbook rear-guard actions fought by Australian units, which allowed 50,732 men to escape the grasp of the advancing superior Axis force. But why were Australian units involved in Greece in the first place?

By Brendan Spencer.

Australia’s commitment to the Second World War is astonishing, 14.25% of its population was mobilised with around 993,000 serving in Australia’s armed forces during the war. Initially Australian forces were committed to the Mediterranean, North Africa and the Middle East, helping Britain defend her imperial possessions and fight the Axis nations. Australians served alongside the New Zealanders in the ANZAC Corps, the only time the corps would exist during the Second World War. But after the declaration of war by the Empire of Japan Australia’s focus shifted to home defense. This helps to explain why the Greek campaign has been overlooked in Australia, despite the very significant part played by Australians.

The Allies deploy to Greece

The Greek campaign had few of the big battles or the world changing consequences of the Battle of France or the Battle of Britain in 1940. It was a key moment in Allied strategy in the Mediterranean, but for the wrong reasons. The Allies sent 63,000 men to help Greece counter a German invasion. This was named W-Force and it included the Australian 6th Division led by Major-General Sir Iven Mackay. This included the Victorian 17th Australian Infantry Brigade, comprising the 2/5th, 2/6th, 2/7th battalions, as well as the 2/2nd Field Regiment, a Victorian artillery unit. It also included the 16th Australian Infantry Brigade from New South Wales and the 19th Australian Infantry Brigade drawn from multiple states, which included the Victorian 2/8th battalion.

These forces were veterans of the North African campaign and were taken from the Libyan front after their stunning success against the Italians. They were heavily involved in the rear guard fighting that would come to define the campaign in Greece. Allied forces had been in action in Greece for 6 months prior to the German invasion, with R.A.F units supporting the Greeks in their war against the invading Italians. This should have given the Allies time to make a detailed plan for the defence of Greece. This was not done effectively and the deployment of Allied forces was chaotic. Private Roy Heron from Albany, WA, who had previously defeated the Italians at Bardia, remembers that they had no idea why they were being sent to Greece, what they were to do or how long they would be there.

When the Australians arrived at the port of Piraeus and marched through Athens they were cheered by the civilians and welcomed like heroes. Many Australians enjoyed their time in Greece, especially as the British Pound was very strong against the Greek Drachma meaning they could spend lavishly on their low army wages, with one soldier remembering how the local village baker had to borrow money from the whole village to give the soldier change. The Australians enjoyed the Greek countryside and saw a lot of it while travelling up the country to reach their defensive positions. When they moved to Florina on the Greek Yugoslavian border the weather turned awful, the soldiers had a hard time adjusting from the heat of the North African desert to the snowy hills of Northern Greece.

The German Invasion of Greece

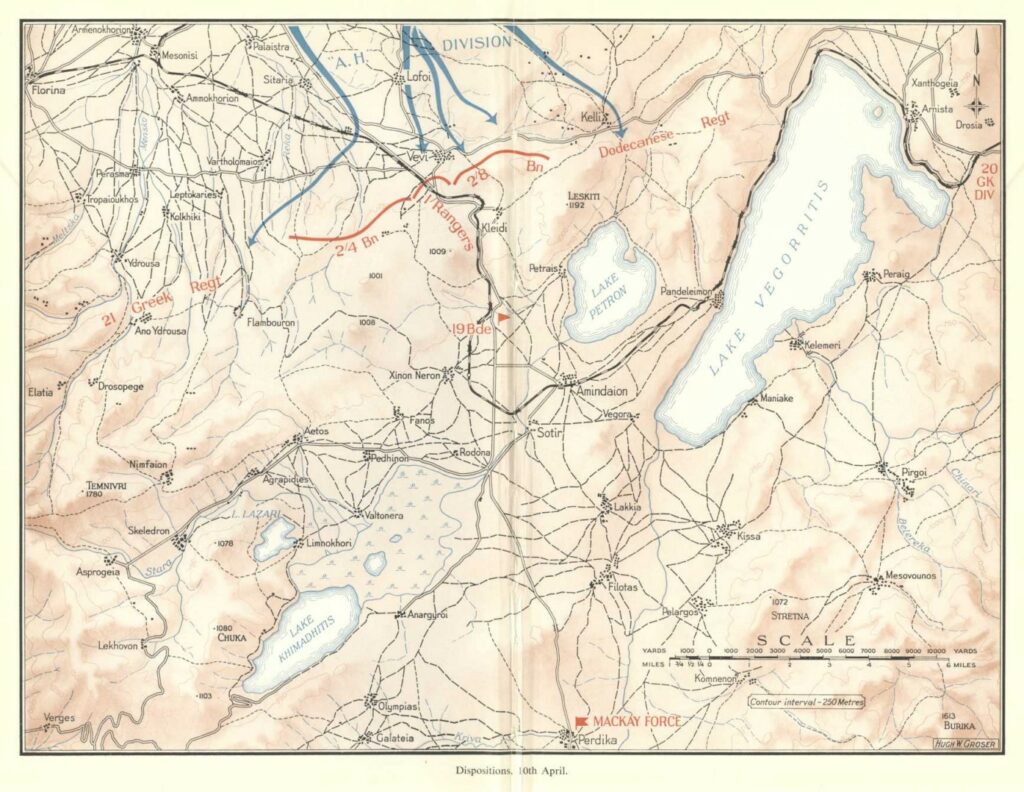

The Germans started Operation Marita, their invasion of Greece, on the 6th of April 1941. The first major engagement the Australian forces were involved in was on the night of the 10th April 1941 near Vevi on the Greek-Yugoslav border.

The forward elements of the 1st SS Division Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler crashed into the Australian 2/4th and 2/8th battalions, who had only moved up to their positions in the previous 24 hours. Weather conditions were less than ideal, Sgt Rex Yeomans of the 2/3rd Field Regt remembers that the weather was awful, with the snow making it harder to engage the enemy. The Australians had to hold a 4 km front, which they did well, repulsing multiple attacks by the SS regiment. The Australian artillery was quite effective in stopping the German tanks and mechanised forces. After two days of near continuous fighting with little sleep the Australian position had deteriorated. A significant part of B Company, 2/8th battalion were killed, wounded or captured and the Australians were forced to withdraw. This in itself was far from easy, but the Australians maintained their cohesion while disengaging under fire for 10km.

Retreat and Pinios Gorge

While in the process of withdrawing from Northern Greece the Australian 19th Brigade was deployed south of Siatista, while the Victorian 17th Brigade (known as Savige force due to their commander), was kept as a rear-guard at Kalabaka. Savige force held this defensive line until they disengaged on the night of the 17th-18th April. The withdrawal was hard for the Australian units, William Osborne, a gunner with 2/3rd Field Regiment, recalled that the roads were filled with refugees making their way south and there were constant attacks from Luftwaffe aircraft during the day. As a result they travelled almost exclusively by night, but the retreat didn’t result in panic or chaos. This was the experience of much of W-Force, but the ANZAC forces were usually the ones tasked with providing the rear-guard.

Elements of the 2/2nd and 2/3rd battalions alongside some New Zealand units fought a rear-guard action at Pinios Gorge on the 17th-18th April. Major-General Sir Iven Mackay had prepared for the defence of this area by removing all of the heavy equipment from the north side of the Pinios river, then blowing up all the bridges over it. This bought the ANZAC forces time to create a defensive position where they could hold the Germans while the remainder of W-Force was evacuated. However the ANZAC forces had too few units to guard the whole riverbank against a German crossing so they relied on their Bren Gun carriers to provide a quick counter attack wherever the Germans crossed.

The 2/3rd Battalion were exhausted after their retreat south, were depleted by casualties they had suffered and men who had become separated from the unit. William Jenkins, of the 2/3rd battalion recalled moving into the defensive positions at Pinios Gorge as wounded New Zealanders were being withdrawn. William, from Newtown, NSW had worked in the Chubb safe factory before the war and gave a false name when he joined the 6th Division in order enlist without his parent’s permission. He also had better memories during the retreat of finding an abandoned NAAFI canteen in the heavily bombed town of Larissa. He was happy to have stopped the Germans getting their hands on the food, beer and supplies!

The forces at Pinios Gorge had to hold a 5km long line against a highly experienced German force of the 6th Gebirgs Division that was backed up tanks from the I/3 panzer regiment. On the 18th April at 7:00 the German XVIII Mountain Corps launched an assault against the 2/2nd Battalion, this was combined with an assault on the New Zealand positions. The ANZAC’s were also under constant air attack by up to 30 German dive bombers at a time. By the end of the day both units had to fall back, but they had managed to hold the Germans up for 24 hours. This delay meant that W-Force was able to make it to the Thermopylae line. They had done their job well.

The withdrawal from Pinios gorge followed the now familiar process of the Australian rear guard attempting to reach the next defensive position far enough ahead of the Germans to establish firm defences. Neville Blundell of the 2/3rd Battalion, describes it well.

We were on trucks… you had to keep an air raid alert. There were a couple of blokes standing by the back of the cabin with the cover pulled back so we could see what was coming. When the planes approached we used to bang on the lid and they’d pull up. Everyone would dive out and get as far away as they could in the time they had. Two blokes got wounded during one attack… Then it was just to keep going day after day. We’d move in the night and hide in the day.

Neville Blundell of the 2/3rd Battalion

Neville, a tool maker from Tempe, NSW enlisted in the 6th Division the day Australia declared war on Germany. He is part of a very small group of Australian soldiers who fought against each of Australia’s enemies in WW2. He fought the Italians at Bardia, the Germans in Greece, the Vichy French in Syria and the Japanese in the Pacific.

Thermopylae and Evacuation

The 24th of April saw an acceleration of the withdrawal of W-Force from Greece. It continued each night, with troops and equipment being taken off by the Royal Navy and Royal Australian Navy from the port of Porto Rafti. This evacuation was covered by the Thermopylae line, manned by Allied forces that now had extensive experience preparing new defensive positions quickly. The 19th Brigade, commanded by Brigadier George Vasey from Kew, Vic were assigned the rear guard position around the village of Brallos. Vasey, whose nickname was “Bloody George” was typically blunt in his instructions.

Here you bloody well are and here you bloody well stay. And if any bloody German gets between your post and the next, turn your bloody bren around and shoot him up the arse.

Brigadier George Vasey, commander of the 19th Brigade at the Thermopylae line.

The terrain of the Thermopylae line favoured the defenders, with the rough ground making it hard for the German tanks. Michael Lardelli , who was a sugar cane farmer from near Townsville, QLD, of the 2/1st Battalion remembered ‘the terrain was too rough and mountainous particularly around the pass it was very very rugged country’. The German attack came on the Thermopylae line on the 24th April as elements of the 6th Mountain Division attacked the Australians at Brallos, but they met fierce resistance. The Australians were under constant air attack from Luftwaffe dive bombers, Ronald Currie, of the 2/7th Battalion describes his experience.

they used the Stukas and they would mainly use them prior to an attack. Whenever you got a bad Stuka raid, you knew there was going to be an attack coming… in my book he was the best soldier in the world at that time, the German, and he had the best equipment. His artillery, I remember one night on Brallos Pass we, putting up a stand, but we was right on top of a mountain and there was all rock, you couldn’t dig in, you might get behind a bit of a rock… that was the worst fright I ever got. Oh you could hear the bloody things coming, whistling, crashing into the bloody bare rock. Pieces of rock going everywhere… it’s a wonder any of us got out of it.

Ronald Currie, 2/7th Battalion.

Ronald Currie was a farmer from Narre Warren, Victoria. He trained at the Flemington Showgrounds and Puckapunyal before seeing action against the Italians at Bardia.

The ANZAC’s held the Thermopylae line against a full day of determined attacks from the Germans, destroying 16 German tanks in the process. They were then ordered to withdraw, their delaying action giving the remainder of W-Force time to evacuate. They pulled back in good order, managing to take most of their equipment with them. The exhausted Germans failed to press home their attack.

It was now a race against time for the Australians to reach the evacuation points before the advancing Germans cut them off. Most of the troops were able to make it to the evacuation ports or beaches, although a total of 26 Allied ships were sunk by German air attack during the evacuation. The ship evacuating Ronald Currie, who was from Narre Warren, VIC, was torpedoed, but he still managed to make it to Crete, which was the site of a German airborne invasion shortly afterwards. The greatest tragedy of the evacuation was the sinking of the Dutch troopship Salamat and the Royal Navy destroyers HMS Diamond and HMS Wryneck by the Luftwaffe with the loss of 983 men including at least 31 Australians and likely many more. This was a result of the ships remaining in the port of Nafplio for too long loading evacuees. This meant they hadn’t got far enough away from Greece by first light and were found and sunk by German aircraft.

The Australian experience in Greece

The Australians fought a good campaign overall. They were involved in most of the fighting that occurred and were not decisively beaten on the battle field. Their casualties were relatively light considering all of the fighting they took part in. The Australians suffered 320 killed in action, 494 wounded and 2030 captured. Listen to an incredible story of one of these POW’s in Escape from Greece. The Australian and ANZAC forces were not beaten because they weren’t as skilled as the Germans but because they were vastly outnumbered and had little air support. In their reports after the battle the 1st SS division recorded that the Australians and New Zealanders had fought an outstanding defensive battle and used the terrain well. Coming from their enemy, this is significant praise.

Newsreel Footage of the Campaign

Podcasts about the Greek Campaign

This project commemorating the service by Victorians in the Mediterranean theatre of WW2 was supported by the Victorian Government and the Victorian Veterans Council. Sign up to the newsletter at the bottom of the page to be notified when the next article in this project is released.

Articles you may also like

Escape from Greece – Podcast

ESCAPE FROM GREECE – PODCAST This podcast episode tells the story of Shanghai born John Robin Greaves, ‘Jack’, who emigrated to Australia in 1939 and volunteered for the Australian Imperial Force to serve overseas. The army would send Jack to the Middle East, then to Greece, where he would be captured Germans along with thousands of other […]

The Benghazi Handicap and the Siege of Tobruk

The Benghazi handicap is the name Australian soldiers gave to their race to stay ahead of the German Afrika Korps in Libya, 1941. They won the race, but the reward was just to be besieged in the city of Tobruk for 241 days, the longest siege in British military history. In this article, we use the words of veterans themselves to describe these events, and how the Rats of Tobruk experienced the siege.

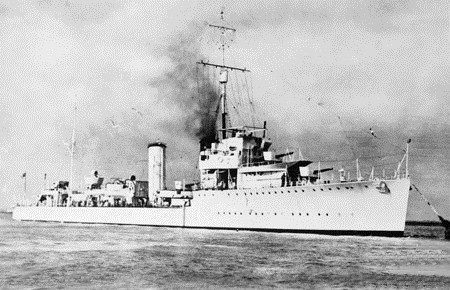

Scrap Iron Flotilla: The Royal Australian Navy at its Best

To the Axis Powers, the Australian flotilla that fought in the Mediterranean during the Second World War appeared to be no threat. Anyone looking at the old, small and slow destroyer group would think the same. Soon, however, the Axis and the rest of the world would learn just how formidable it was. The ‘Scrap […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.