Reading time: 6 minutes

The 30 Years’ War is remembered by few people except historians, but the conflict, which raged across Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, had a deep and lasting impact on the continent. It involved all major European players at the time, from the German states — where most of the fighting was done — to Spain, France, Denmark and Sweden. With such eclectic combatants, you might be surprised that the events that kicked off the war took place in Prague.

By Fergus O’Sullivan

The Thirty Years’ War is interesting for a few reasons. For one, it lasted a long time: people born in the first few years could have found themselves its victim even as adults. The reason it lasted as long as it did is because every few years a new combatant would find themselves dragged into the vortex in the middle of the continent, extending the fight even more.

The drawing power of the Thirty Years War lay in the fact that there was something at stake for everybody: it was part of the European wars of religion between the Catholic Counter Reformation and the different flavors of Protestantism, it was part of the Habsburg struggle to control ever more land, it was part of the transition from a feudal economy to one based around markets… The list goes on.

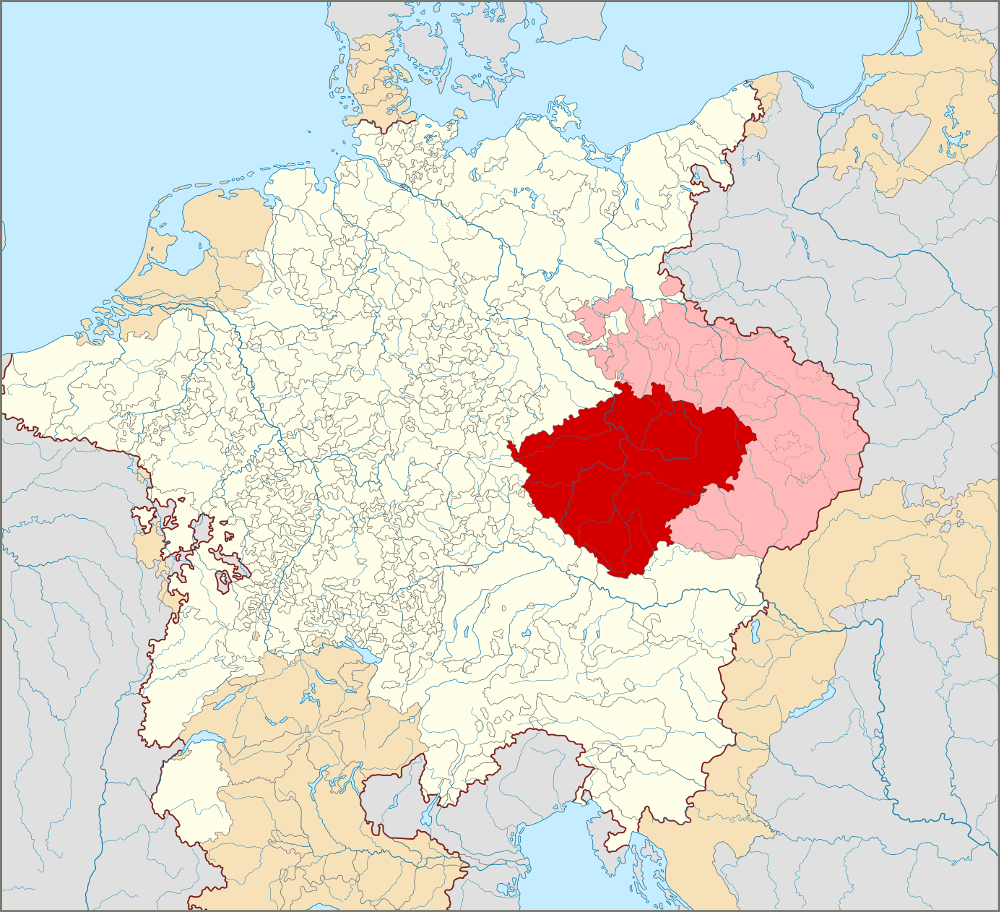

With such a heady mix of ingredients, the flame that set this cocktail alight could have come from anywhere in Central Europe, but it’s not entirely surprising that it sparked in Prague, capital of the Kingdom of Bohemia, more or less the western part of what’s now Czechia (Czech Republic if you’re old-school).

Czechs and Balances

In 1618, the Kingdom of Bohemia was part of the Holy Roman Empire and had Catholic, Austrian Habsburg kings. The people that lived there, though, were by and large Czech and Protestant. Generally speaking, the rulers let sleeping dogs lie and didn’t interfere with Protestants exercising their faith, even allowing churches to be built on government lands.

This changed with the accession of Ferdinand II to the Bohemian throne — a stepping stone to his eventual taking up the imperial mantle. Ferdinand was a big fan of the Counter Reformation, the Catholic movement that aimed to restore all Protestants to the Mother Church by force if need be, and he reversed this long policy of relatively peaceful coexistence.

The Defenestration of Prague

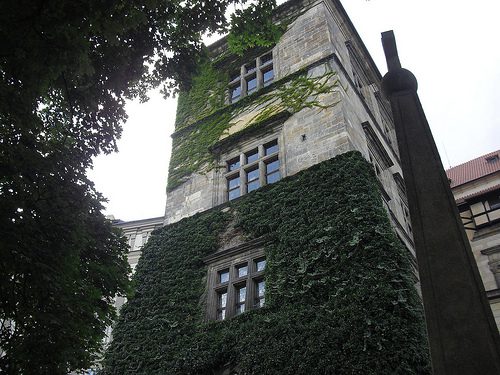

Ferdinand despatched four Catholic noblemen to Prague castle with a letter to give to a gathering of local, Protestant nobles to quit building churches on government land (among other things). The tone of the letter angered the Czechs and they turned on the envoys, though not before letting two of them go as they were considered too decent to be behind the king’s machinations.

One of the Protestant leaders accused the two remaining envoys by saying: “You are enemies of us and of our religion …[and] have horribly plagued your Protestant subjects … and have tried to force them to adopt your religion against their wills or have had them expelled for this reason.” He then turned to his fellow Protestants and continued, “Were we to keep these men alive, then we would lose … our religion … for there can be no justice to be gained from or by them.”

This was the cue for the rest of those gathered two grab the two envoys — and sadly, one of their secretaries — and throw them from the nearby window. Somehow, all three survived the 21-meter fall, with Catholics claiming divine intervention in the form of an angel catching them and Protestants stating a dungheap had broken their fall.

Interestingly enough, this wasn’t the first time the Czechs had thrown people they didn’t like out of a window, or even the second. Officially, this is known as the Third Defenestration of Prague, proof that Czechs are people that place great emphasis on tradition.

The Battle of White Mountain

Having his envoys chucked out of a window unsurprisingly angered Ferdinand, and it didn’t help that a year later, when he ascended to emperor, the Bohemians replaced him by electing the Calvinist Frederick IV as king. This was a poke in the eye for the Catholic fanatic, and he raised an army to teach the rebellious Czechs a lesson.

The Czechs organized their own army, and met the invader near White Mountain, a site outside Prague (now in city limits, but only by a hair). However, the rebels were outmatched in both arms and numbers and lost the battle decisively, leaving the victorious army to enter Prague and take the city.

Ferdinand wasted little time and put 47 ringleaders on trial. The proceedings were fair enough, apparently, because in the end only 27 of them were sentenced to death. The beheadings were carried out on June 21, 1621 on Old Town Square, just around the corner from what’s now Prague’s biggest attraction, the mechanical astronomical clock

The heads of the men were gathered up and hung from Prague’s other tourist site, the Charles’ Bridge, to serve as a grisly warning for Protestants, rebels, and anybody else that would challenge the might of his Catholic Majesty.

In the end, though, these events would only be the starting point to one of the bloodiest conflicts in European history. Though they didn’t know it at the time, the Czech nobles defenestrating those envoys set in motion a chain of events that would draw in all European powers and cause the deaths of millions. A heady mix, indeed, and one you can learn more about with the below video.

Articles you may also like

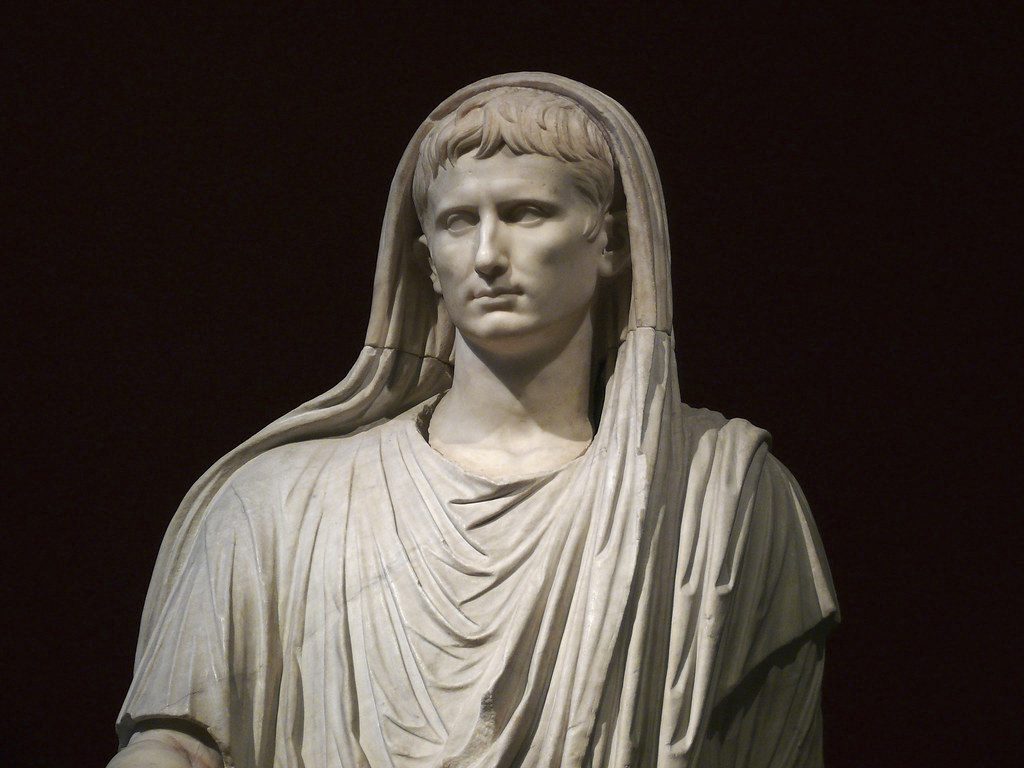

ROME’S AUGUSTUS AND THE ALLURE OF THE STRONGMAN

ROME’S AUGUSTUS AND THE ALLURE OF THE STRONGMAN The Roman emperor Augustus is held up by some as a statesman who brought peace, and as a potential model for the future. But what was the cost of Augustus’ peace, and how real was it? On his 2012 honeymoon to Rome, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg took […]

The Siege of Haarlem, Kenau, and Creating a Heroine

The Dutch Revolt, the conflict that created an independent Netherlands free from Spain, also created a lot of legends around events and people, placing them firmly in the shared consciousness. One of the more interesting of these people is Kenau Simonsdochter Hasselaar, a woman who played an important part in the ultimately failed defence of […]

Why the Legions Beat the Phalanx

The societies of ancient Greece and Rome valued brawn as well as brains. Philosophers fulfilled military service and some of the most masterful speeches held in the senate or agora argued for war. However, it was the Romans that would end up dominating the Greeks, which was largely to do with the way they fought […]