Reading time: 6 minutes

The past is back at the center of today’s politics.

The invasion of Ukraine by Russian forces on 24 February has highlighted Putin’s imperial instincts, the Russian coverage is determining future historiography, and the bogus historical claims of a mythical unity of Russian and Ukrainian people dating back to Kievan Rus seem to underlie a strategy of systematically targeting cultural heritage sites.

By Ruben Zeeman, Network of Concerned Historians.

Simultaneously, Katie Stallard has connected official history politics in Russia, China and North Korea, concluding that the greatest threat of abuse of history is the “claim that… their nation is under threat, and that they must strengthen their military capabilities” – exemplified by the invasion of Ukraine, and feared in a potential invasion of Taiwan.

This focus on the outward-directed dangers is justified, but it should not overshadow that most of the negative effects of official abuse of history are experienced by historians and others concerned with the past inside a country. This is the case in Russia and China, as well as in countries recently appearing on the margins of international news: Rwanda and Sri Lanka. The threats faced by history producers within these countries can be illustrated by two types of historical abuse by governments: the persecution of history producers, and the suppression of commemorative events.

In March 2022, overshadowed by British asylum policies, Human Rights Watch (HRW) published its findings about the state of free speech in Rwanda. In 2018, the government of President and “darling tyrant” Paul Kagame adopted the latest version of a law making punishable, by up to seven years imprisonment, public speech questioning the events and statistics related to the 1994 Genocide. However, the law lacks clear definitions and its vague language is seen as instrumental in prosecuting legitimate debate, in particular over crimes committed by the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), of which Kagame was the commander. Prosecution of legitimate historical discourse took place under earlier versions of the law, but in the lead-up to the thirtieth anniversary of the 1994 Rwandan genocide, the Kagame government has increased its efforts to combat “genocide ideology.”

There are numerous examples. On September 30, 2021, online commentator Yvonne Idamange was sentenced to fifteen years in prison and a 2 million Rwandan Francs fine ($1,930) for denigrating genocide artifacts and minimizing the genocide. In fact, Idamange had criticized the ways in which the genocide was commemorated, arguing that remains of the victims should not be on display at memorials, and had drawn attention to crimes that were committed by the RPF in the genocide’s aftermath. Similarly, Aimable Karasira, another online commentator and a former professor of information communication technology at the University of Rwanda, was dismissed in August 2020 and arrested on May 31, 2021, for having discussed killings by RPF soldiers. Moreover, in February 2020, gospel musician Kizito Mihigo was found dead in a police cell. In 2014, he had released the song Igisobanuro Cy’urupfu (The Meaning of Death), suggesting that national remembrance should include all victims of the genocide. Following the release, he was arrested and sentenced to ten years in prison for conspiring against the government. His music was banned. Kizito was pardoned in 2018, but again arrested on February 13, 2020. Government critics believe he was murdered.

In Sri Lanka, the government has used legal resources to ban commemorative practices. On May 18, the first-ever public vigil for the Tamil victims of the Civil War (1983-2009) was held in Colombo. Thirteen years prior, on May 18, 2009, governmental forces led by then-President Mahinda Rajapaksa had killed Velupillai Prabhakaran, leader of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), effectively ending the war. Since then, May 18 has been the national Remembrance Day to mark the capitulation of the LTTE. As early as 2011, a United Nations’ panel of experts had concluded that the government held a tight grip on commemorative practices. This impacted especially the annual vigil for the Tamil people who had died during the war.

The government’s grip on commemorative practices has only grown worse during the presidency of Gotabaya Rajapaksa, characterized by a general unwillingness to ensure accountability for crimes committed during the war. In 2019, Rajapaksa, who was top defense strategist during the presidency of his brother Mahinda, fully prohibited the commemoration of the LTTE. In September 2021, Tamil Member of Parliament Selvarajah Kajendran was arrested for commemorating an LTTE-member. In late November, relatives of deceased LTTE-members were forced out of cemeteries by armed troops. The Mothers of the Disappeared, protesting for information about disappearances that occurred during the war, were attacked by police on 20 March 2022. This year’s vigil in Colombo, instead of indicating a more inclusive space for commemorations, rather seems to be the effect of the immense economic pressures on Rajapaksa.

Events in Sri Lanka and Rwanda are mirrored in China and Russia. In mainland China, even searching for number combinations such as 6-4, 63+1 and 35 has been censored as it might refer to the June 4, 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre. Meanwhile, Hong Kong hosted the only large-scale commemoration of the massacre. However, since 2020 the vigil has been banned, as it challenges the presentation of an upward development from the founding of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1921. In November 2021, the sixth plenary session of the CCP Central Committee passed its third ever resolution on China’s history, in which it praised Xi Jinping’s “historic achievements” within the CCP’s 100-year history.

In Russia, the persecution of history producers began well before the invasion of Ukraine. Most recently, historian Yuri Dmitriev was sentenced to fifteen years on bogus charges of pornography. Working as the head of the Karelian chapter of Memorial, a history NGO investigating Soviet-era crimes, his research had identified around 13,000 victims of the Great Terror (1936-1939). In December 2021, the Supreme Court went even further and ordered the complete liquidation of Memorial, accusing it of distorting historical memory and portraying the USSR as a terrorist state.

These are only a few examples of abuses of history by governments – the Annual Reports of the Network of Concerned Historians testifies to the large and global scale. The effects of historical manipulation are most severely felt by the historians and history practitioners within these history-twisting regimes. They are seen as especially threatening when their work is able to undermine the carefully constructed singular interpretation of history that functions as one of the foundational pieces of the political reign: whether projected as the defender of order and stability after conflict (Kagame, Rajapaksa), or as the guardian to continue the great achievements of the past and protect them against “foreign (Western) influences” (Xi, Putin).

This demonstrates that official attempts to hinder bona fide historical research and debate through legislation or other means, are the first signals that history is at risk of abuse – an important warning for the United States as well.

This article was originally published in The History News Network.

Podcasts about political prosecution in Rwanda:

Articles you may also like:

The Medici, Volume 2 -AUDIOBOOK

THE MEDICI, VOLUME 2 – AUDIOBOOK By G. F. Young (1846 – 1919) This work relates the history of the Medici family through three centuries and eleven generations, from its rise from obscurity, to its zenith of power and influence, to its eventual decay and ruin. It outlines their history in conjunction with the major events […]

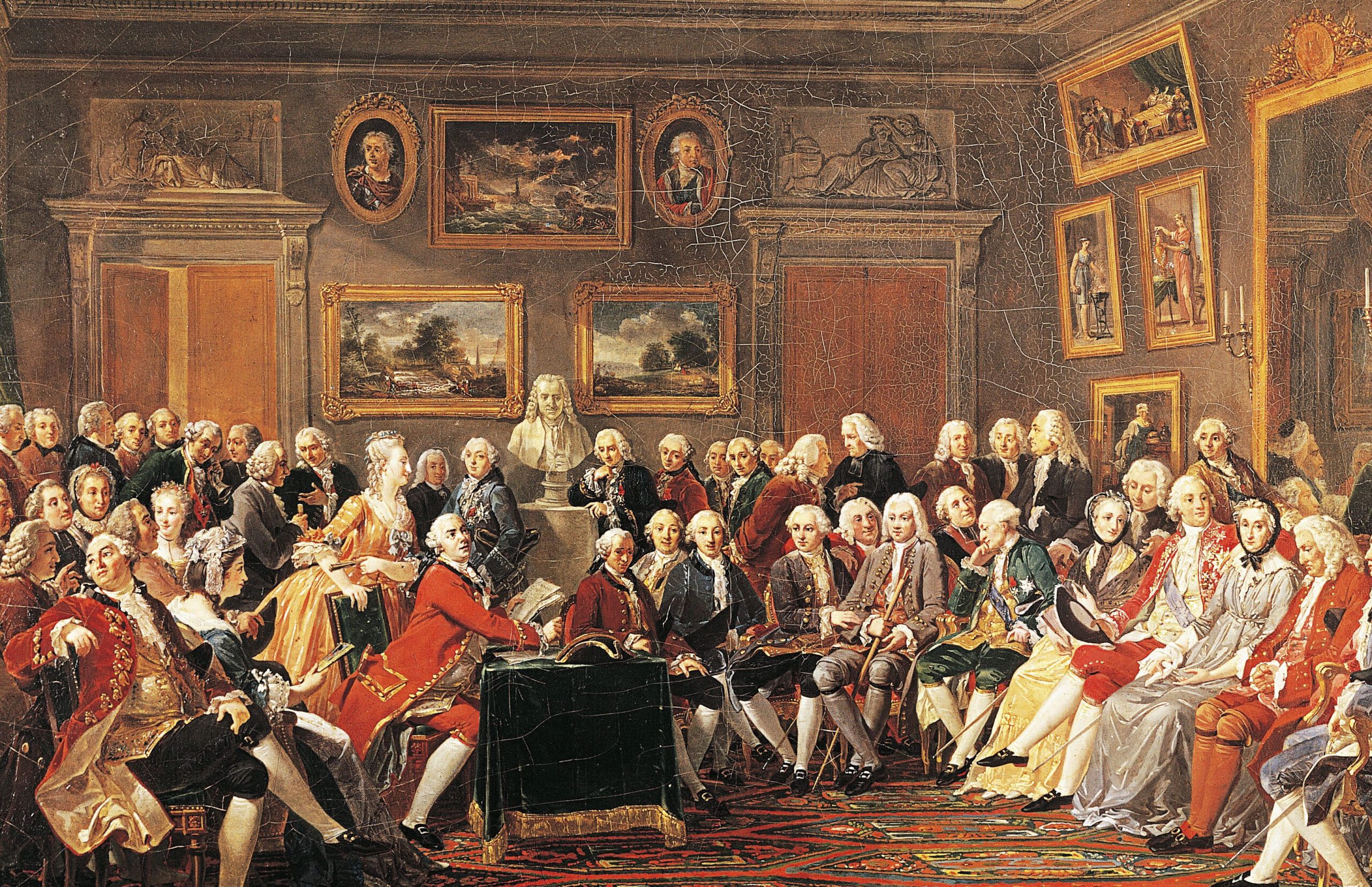

Voltaire and the French Enlightenment – Audiobook

VOLTAIRE AND THE FRENCH ENLIGHTENMENT – AUDIOBOOK By Will Durant (1885 – 1981) n this Little Blue Book Number 512, Will Durant describes François-Marie Arouet, the writer, historian, and philosopher known as Voltaire (1694-1778) as “unprepossessing, ugly, vain, flippant, unscrupulous, even at times dishonest” and “tirelessly kind, considerate, …as sedulous in helping friends as in crushing […]

The text of this article is republished from HNN in accordance with their republishing policy.