Reading time: 7 minutes

On this day, February 29, conversations the world over may conjure the name of Pope Gregory XIII – widely known for his reform of the calendar that bears his name.

The need for calendar reform was driven by the inaccuracy of the Julian calendar. Introduced in 46 BC, the Julian calendar fell short of the solar year – the time it takes Earth to orbit the Sun – by about 12 minutes each year.

By Darius von Guttner Sporzynski, (Australian Catholic University )

To correct this, Gregory convened a commission of experts who fine-tuned the leap-year system, giving us the one we have today.

But the Gregorian calendar isn’t the only legacy Pope Gregory left. His papacy encompassed a broad spectrum of achievements that have left a lasting mark on the world.

Rise to papacy

Born in 1502 as Ugo Boncompagni, Gregory made many contributions to the life of the Catholic Church, the city of Rome, education, arts and diplomacy.

Before ascending to the papacy, Boncompagni had a distinguished career in law in Bologna where he received his doctorate in both civil and canon law. He also taught jurisprudence, which is the theory and philosophy of law.

His intellectual influence positioned him as a trusted figure in legal and diplomatic circles even before his election as pope in the 1572 conclave. Upon being elected he adopted the name Gregory, in honour of Pope Gregory the Great who lived in the sixth century.

Movement in the Church

One of Gregory’s major undertakings was reforming the Catholic Church in response to the Reformation, a movement which established a distinct new branch of Christianity, Protestantism, separated from the Catholic Church.

Gregory aimed to implement the decisions of the Council of Trent, which met between 1545 and 1563, and defined key Christian doctrines and practices, including scripture, original sin, justification, the sacraments and saint veneration. Its outcomes directed the church’s future for centuries.

Gregory’s administrative reforms were aimed at centralising church governance and its operations. As pope, he relished the practice of law, personally engaging in judicial deliberations and surprising his contemporaries with his legal acumen.

His papacy also marked a revision of Gratian’s Decretals, a collection of 12th-century church laws that served as a textbook for lawyers. Gregory aimed to correct numerous errors and unify the various versions of this foundational text of canon law. This culminated in the publication of an amended edition in 1582.

Gregory’s dragon

Pope Gregory lived at a time when emblematic and symbolic interpretations were central to the political and cultural discourse. In particular, monsters were interpreted as omens or divine signs and played a significant role in religious and political debate.

Gregory’s coat of arms, the heraldic emblem of the Boncompagni family, featured a dragon. As such, it drew criticism from Protestant propaganda.

Anti-Catholic publications featured the Boncompagni dragon as an emblem of the Antichrist, drawing on the seven-headed monster in the Book of Revelation.

Rooted in biblical and mythological references, the negative imagery of Gregory’s dragon became a focal point for debates over the nature of papal authority, the legitimacy of Protestant criticisms, and the broader struggle to define truth and meaning in a rapidly changing world.

A legacy enshrined in art

Gregory’s legal legacy is celebrated in art, particularly in the Sala Bologna of the Vatican Palace, which commemorates his and other popes’ contributions to the study and codification of law.

Gregory XIII’s pontificate (term of office) was marked by a comprehensive effort to renew and beautify Rome, improving both the city’s functionality and aesthetics. He had a particular focus on the Capitoline Hill, the political and religious heart of Rome since the Antiquity.

Gregory’s initiatives – which included restoring essential infrastructure such as gates, bridges and fountains – were part of a broader vision to emphasise the centrality of law in Rome’s history and culture.

This is demonstrated by him being honoured by a statue in the Aula Consiliare of the Senator’s Palace. This hall was designed to showcase the importance of judicial proceedings.

Alongside his urban planning initiatives, Gregory’s commissioning of artworks and architectural projects showcased his commitment to fostering a city that was not only the spiritual centre of Catholicism, but also a beacon of Renaissance culture.

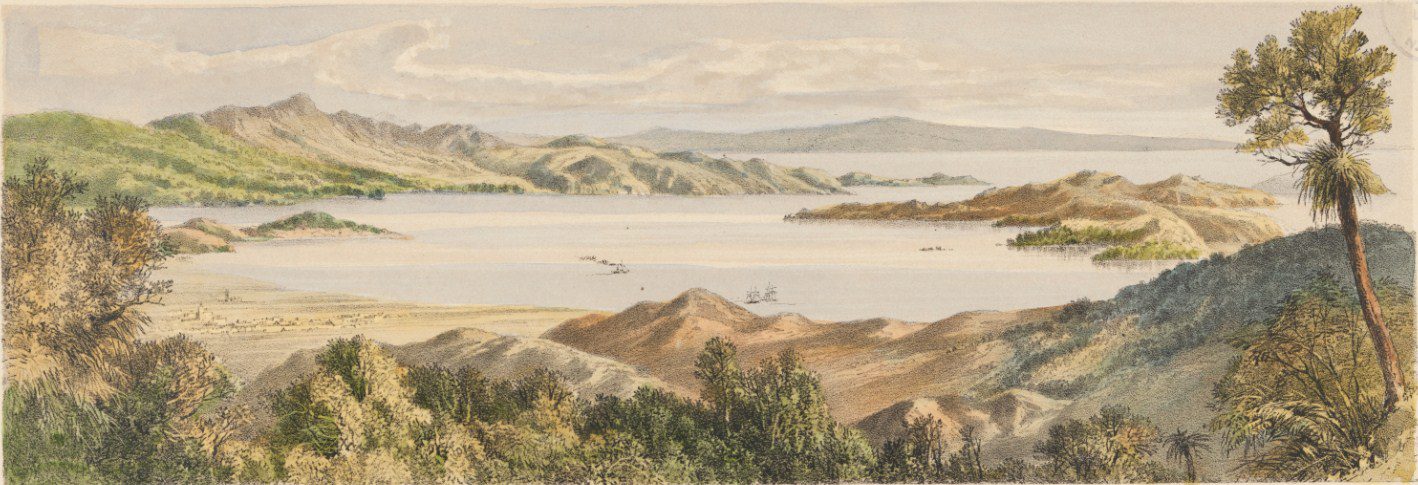

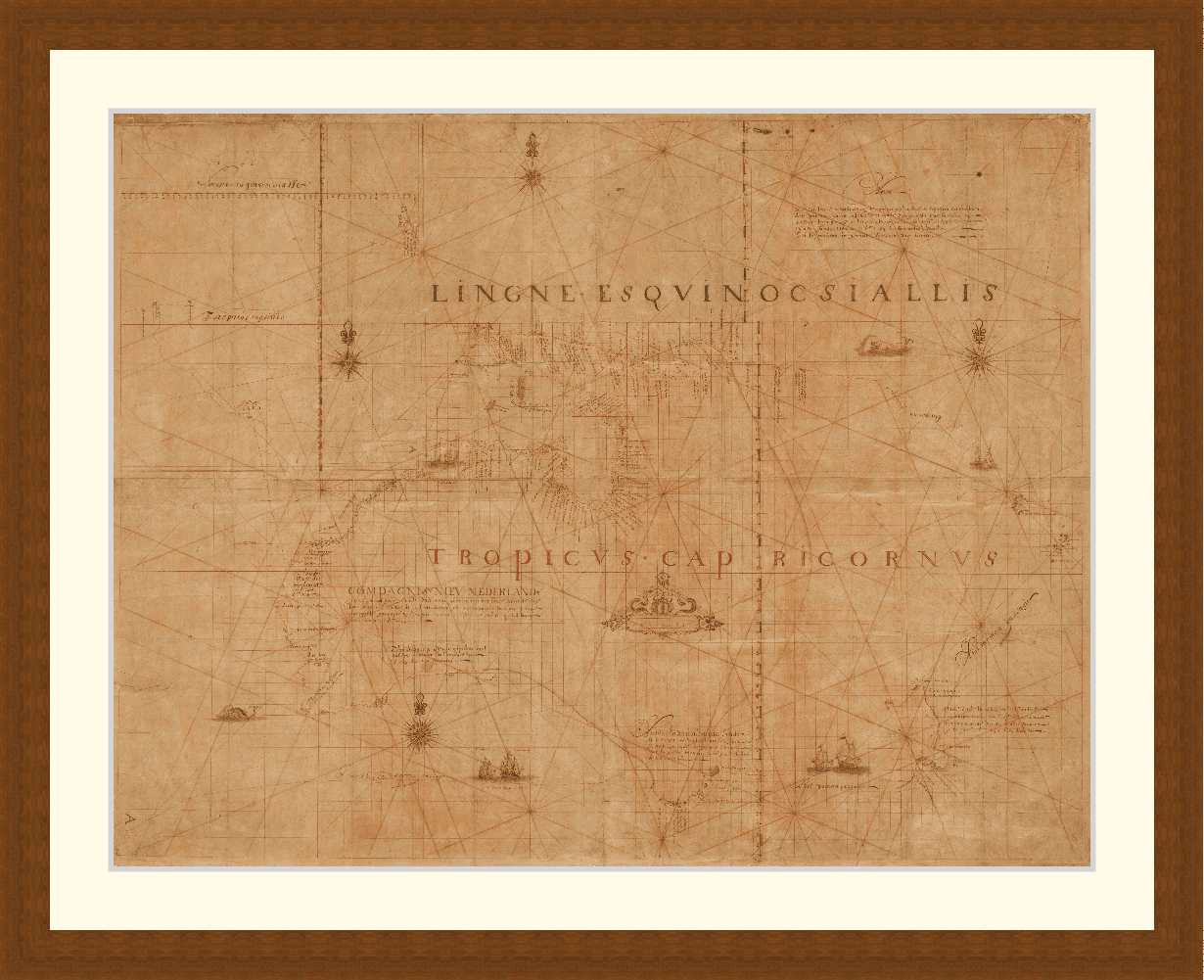

In the Sala Regia hall in Vatican City, he commissioned a series of mural frescoes showcasing the triumph of Christianity over its enemies. He also commissioned an entire map gallery for the Apostolic Palace, to demonstrate the extent of Christianity’s spread over the world.

Reforming the calendar

Because the Julian calendar fell short by about 12 minutes each year, it was increasingly out-of-sync with the solar year. By the time Gregory’s reign began, this discrepancy had accumulated to more than 10 days.

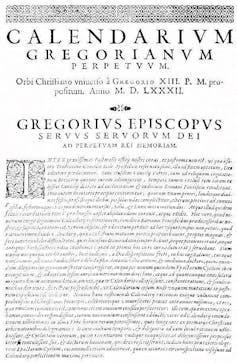

To correct this, Gregory convened a commission of experts. Their work led to the publication of a formal papal decree in the form of the bull Inter Gravissimas on February 24 1582.

This decree not only fine-tuned the leap-year system, but also mandated the elimination of ten days to realign the calendar with the solar year.

The Gregorian calendar reform signified a monumental shift in timekeeping. In 1582, October 4 was followed directly by October 15, correcting the calendar’s alignment with astronomical reality.

This adjustment, slowly adopted by Protestant nations, has had a lasting impact on how the world measures time.

Faith, intellect and reform

In St Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City, you will find a remarkable funerary monument to Pope Gregory XIII. Completed in 1723 by Milanese sculptor Camillo Rusconi, it incorporates representations of both Religion and Wisdom, personified by two statues flanking the pope.

Wisdom is shown drawing attention to a relief beneath the enthroned pope which illustrates the promulgation of the new calendar – the pope’s most significant achievement. At the base of the monument, a dragon crouches unapologetically.

It’s a fitting tribute to a pope whose tenure was characterised by the interaction of faith, intellect and reform – and which can now be marked as a cornerstone in European history.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about Pope Gregory XIII

Articles you may also like

Christmas History Quiz 2023

1. Which Roman Festival was held on the 25th of December?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.