Reading time: 5 minutes

Granada, in southern Spain’s Andalusia region, was the final remnant of Islamic Iberia known as al-Andalus – a territory that once stretched across most of Spain and Portugal. In 1492, the city fell to the Catholic conquest.

In the aftermath, native Andalusians, who were Muslims, were permitted to continue practising their religion. But after a decade of increasingly hostile religious policing from the new Catholic regime, practising Islamic traditions and rituals was outlawed. Recent archaeological excavations in Granada, however, have uncovered evidence of Muslim food practices continuing in secret for decades after the conquest.

By Aleks Pluskowski (University of Reading), Guillermo García-Contreras Ruiz (Universidad de Granada),and Marcos García García (University of York)

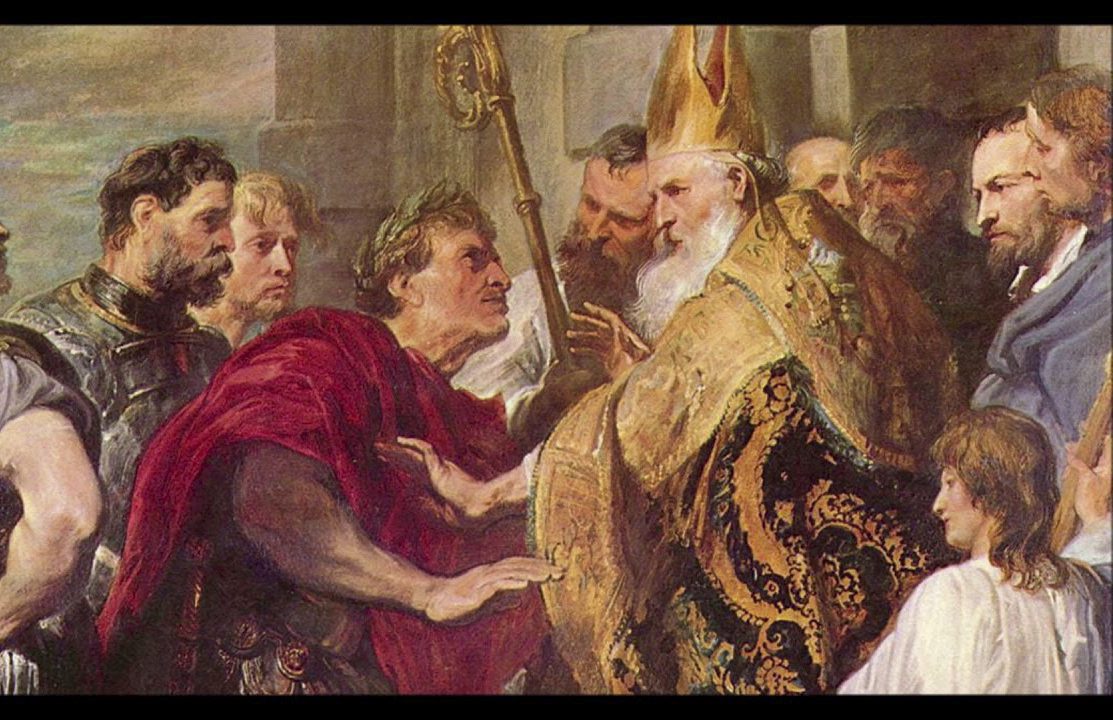

The term “Morisco”, which means “little moor”, was used to refer to native Muslims who were forced to convert to Catholicism in 1502, following an edict issued by the Crown of Castile. Similar decrees were issued in the kingdoms of Navarre and Aragon in the following decades, which provoked armed uprisings.

As a result, between 1609 and 1614, the Moriscos were expelled from the various kingdoms of Spain. Muslims had already been expelled from Portugal by the end of the 15th century. So this brought to an end more than eight centuries of Islamic culture in Iberia.

For many, the conquest of Granada is symbolised by the Alhambra. This hilltop fortress, once the palatial residence of the Islamic Nasrid rulers, became a royal court under the new Catholic regime. Today it is the most visited historical monument in Spain and the best-preserved example of medieval Islamic architecture in the world. Now, archaeology provides us with new opportunities to glimpse the conquest’s impact on local Andalusi communities, far beyond the Alhambra’s walls.

Uncovering historical remains in Cartuja

Excavations ahead of development on the University of Granada’s campus in Cartuja, a hill on the outskirts of the modern city, uncovered traces of human activity dating back as far as the Neolithic period (3400-3000 BC).

Between the 13th to 15th centuries AD, the heyday of Islamic Granada, numerous cármenes (small houses with gardens and orchards) and almunias (small palaces belonging to the Nasrid elite) were built on this hill. Then, in the decades following the Catholic conquest, a Carthusian monastery was built here and the surroundings were completely transformed, with many earlier buildings demolished.

Archaeologists uncovered a well attached to a house and agricultural plot. The well was used as a rubbish dump for the disposal of unwanted construction materials. Other waste was also found, including a unique collection of animal bones dating to the second quarter of the 16th century.

Archaeological traces of culinary practices

Discarded waste from food preparation and consumption in archaeological deposits – mostly animal bone fragments as well as plant remains and ceramic tableware – provide an invaluable record of the culinary practices of past households. Animal bones, in particular, can sometimes be connected with specific diets adhered to by different religious communities.

The majority of bones in the well in Cartuja derived from sheep, with a small number from cattle. The older age of the animals, mostly castrated males, and the presence of meat-rich parts indicates they were cuts prepared by professional butchers and procured from a market, rather than reared locally by the household.

The ceramics found alongside the bones reflected Andalusi dining practices, which involved a group of people sharing food from large bowls called ataifores. The presence of these bowls rapidly decreased in Granada in the early 16th century. Smaller vessels, reflecting the more individualistic approach to dining preferred by Catholic households, replaced the ataifores. So the combination of large bowls, sheep bones paired and the absence of pig (pork would have been avoided by Muslims) points to a Morisco household.

Politicising and policing dining

The Catholic regime disapproved of these communal dining practices, which were associated with Andalusi Muslim identity, and eventually banned them. The consumption of pork became the most famous expression of policing dining habits by the Holy Office, more popularly known as the Inquisition. Echoes of this dining revolution can be seen today in the role of pork in Spanish cuisine, including in globally exported cured meats such as chorizo and jamón.

Previously focusing on those suspected of clinging to Jewish practices (forbidden in 1492), in the second half of the 16th century, the Inquisition increasingly turned its attention to Moriscos suspected of practising Islam in secret, which included avoiding pork. In the eyes of the law, these Muslims were officially Catholic so were seen as heretics if they continued to adhere to their earlier faith. Moreover, since religious and political allegiance became equated, they were also regarded as enemies of the state.

The discarded waste from Cartuja, the first such archaeological example from a Morisco household, demonstrates how some Andalusi families clung to their traditional dining culture as their world was transformed, at least for a few decades.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about Muslim legacy in Spain

Articles you may also like

The Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 01, The Christian Roman Empire and the Foundation of the Teutonic Kingdoms – Audiobook

THE CAMBRIDGE MEDIEVAL HISTORY, VOLUME 01, THE CHRISTIAN ROMAN EMPIRE AND THE FOUNDATION OF THE TEUTONIC KINGDOMS – AUDIOBOOK By John Bagnell Bury (1861 – 1927) Volume 1: The Christian Roman Empire and the Foundation of the Teutonic Kingdoms “The present work is intended as a comprehensive account of medieval times, drawn up on the same […]

Would London Fire Brigades really let your house burn down if you were uninsured?

Reading time: 4 minutes

Here’s an interesting fact: if you didn’t pay your insurance premiums in 17th and 18th century London, firefighters would simply let your house burn, even if they were on the scene. This fact has been repeated many times by many people, so it must be true, right? Or is it?

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.