Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

By Fergus O’Sullivan

World War 1 was a conflict that engulfed entire continents and swallowed up whole generations of men. It is the cause of trauma that has stayed with entire nations, even now, more than a century since it ended. However, for some countries the Great War is no more than a footnote in their history books, and none more so than the Netherlands.

Even as thousands fought and died on the front lines in Flanders, a few hundred kilometers north the Dutch kept safe behind their borders. How a small country, with a population of only about six million in 1910, got away with staying neutral despite being caught between belligerents on three sides is a story of cunning diplomacy, business savvy and incredible luck (much like that of Romania).

As impressive as this is, however, it’s often glossed over in Dutch history textbooks, and popular culture also prefers to focus on the Second World War, when the country suffered a brutal occupation. If you’re making a film or writing a book, there’s more appeal to resistance fighters fighting a doomed struggle than describing what went on during the “fameless years” of 1914 and 1918.

It’s only in this century that this has started to change, albeit slowly. There’s a slow trickle of scholarly work coming out now, with the most comprehensive being the book Buiten Schot (which roughly translates as “dodging a bullet”) by Paul Moeyes. Sorrowfully, it’s only available in Dutch, but it’s excellent; we’ll be using it as the main source for this short piece. For an English-language alternative, you may want to check out The Art of Staying Neutral: The Netherlands in the First World War, 1914-1918 by Maartje M. Abbenhuis.

Setting the Stage

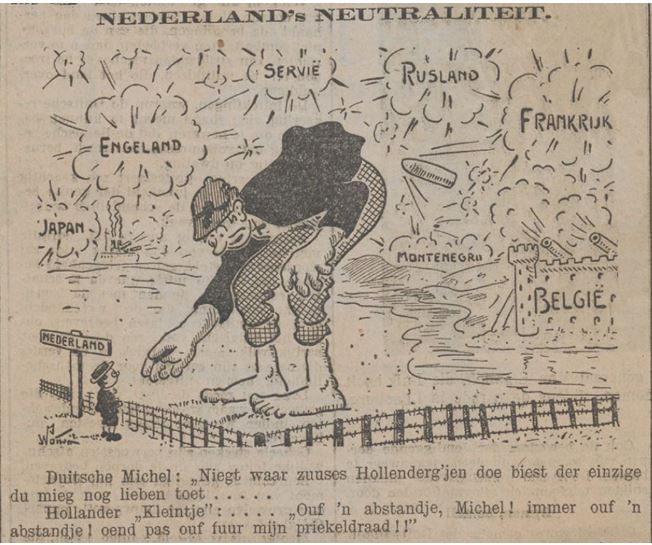

When shots rang out in Sarajevo, there was consternation in the Kingdom of the Netherlands, but it was entirely reserved for itself. During the buildup to WW1, the country had stayed out of the alliances set up by the Great Powers. Despite being a colonial power itself, it didn’t count among the big boys of the European stage, despite its strong economy. As such, it kept itself unofficially neutral as all around it countries geared up for slaughter.

However, unlike Belgium to the south, the Netherlands never had its neutrality guaranteed by a great power, which put it into a position where it pretty much had to walk a tightrope. It had to be careful not to help Britain in any way or risk angering Germany, and vice versa. Meanwhile, both sides would have liked Dutch neutrality to be slanted toward them, making for some tense moments as Dutch politicians slalomed their way through negotiations over trade, treatment of soldiers that came over the border, as well as all manner of other affairs that a neutral country can suffer during a war.

Guarding the Borders

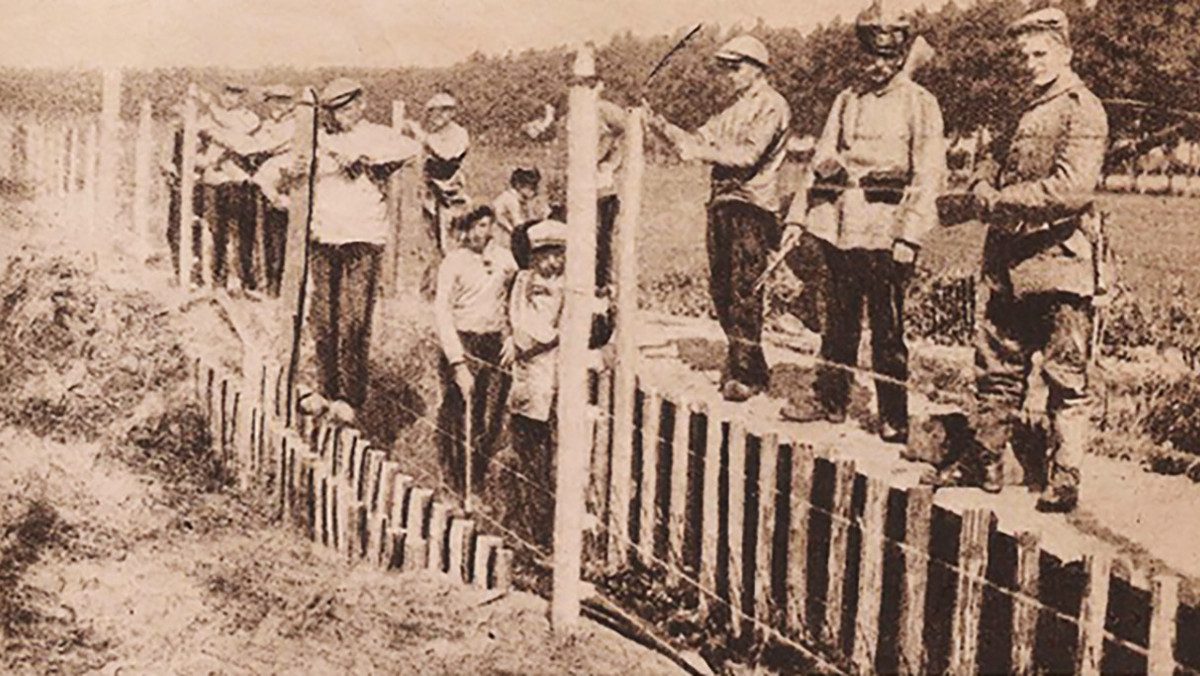

Despite this skillful diplomacy, there was plenty of tension in the air and the armed forces, 200,000 men in all, remained mobilized throughout the war. The army was tasked to guard the borders, while the navy was made into a coast guard that patrolled against any incursion. The border with Belgium was protected by a long line of electric wire, dubbed “the wire of death,” which to this day is still a part of the folklore of the region. That said, smugglers and other people looking to get over the border illegally found plenty of ways to make the wire a lot less deadly, like draping a carpet over it.

Below part of a silent film titled “Army and Fleet,” which shows the cavalry and infantry going through an exercise in what looks like the east of the country.

In the end, though, the main job of both army and navy was to pick up foreign soldiers, sailors and airmen that had wandered into Dutch territory and intern them for the duration of the war. The use of the word “internment” is specific, as none of the men involved were prisoners as such. The camps the enlisted men were put in were of about the quality of their own barracks, while interned officers were usually put up with middle-class families.

In fact, the conditions were so much better than at the front, that at the very start of the war a few deserters made it over into the Netherlands in the hope of getting a spot in a relatively cushy internment camp. The Dutch neutrality declaration, however, made clear distinction between soldiers that accidentally crossed the border and those which did so deliberately, meaning deserters got sent back. In total, about 40,000 men ended up being interned in Dutch camps, the overwhelming majority of them Belgian soldiers.

A Home Away From Home?

Soldiers who had lost their way weren’t the only Belgians that came over: from the very start of the invasion of their country, Belgians sought refuge in the Netherlands. However, with the fall of siege Antwerp in September and October of 1914 this trickle became a torrent as about one million men, women and children fled northward.

This put an immense strain on both Dutch society as well as its economy, though once Germany had restored some kind of normalcy to the parts of Belgium it had occupied, many refugees returned, probably to the relief of the Dutch government. Still, though, many thousands of Belgian refugees stayed, even after the war was over. It’s easy to start a new life in a country with the same language and very similar culture, after all.

A Wartime Economy

Even without refugees, the Dutch economy seriously suffered in the four years the Great War raged. Trade was curtailed thanks to the British blockade of Germany, enforced by constant checks of neutral shipping as well as a minefield in the North Sea. German pressure on Dutch trade came in the form of U-boats, which would pop up in the front of Dutch ships, demanding inspections and even surrender of goods. That was the best case scenario, too: plenty of Dutch ships were lost during the war thanks to British mines and German torpedoes alike.

Trade stabilized from 1915 onward, when the Dutch were able to strike deals with both sides about safe passage and traders were once again able to sell tobacco from the Dutch East Indies on the German market, which filled up the coffers a bit.

Still, though, the economy at large was in dire straits the entire duration: having a big chunk of working-age men in the army on maneuvers rather than at work wreaked havoc on the economy. The result was massive unemployment, which the government struggled to deal with thanks to a dearth of tax income.

Though the Netherlands didn’t suffer the millions of deaths its neighbors did, the years between 1914 and 1918 took a toll in many other ways. That said, to ignore this history has been an oversight. Hopefully plenty more scholars will be able to get to digging through the archives, though it’s a shame we have lost the chance to talk to people who actually lived through it.

Articles You May Also Like

How Romania’s WW1 Gamble Paid Off Spectacularly

Reading time: 6 minutes

The Great War was a major turning point for virtually all European countries, but not too many of them enjoyed a positive outcome. Although it took two years for Romania to enter the war and another two for the conflict to reach a conclusion, the result was an unlikely unification of its historical lands and the beginning of the most prosperous period in the nation’s history.

Between the Lines – Audiobook

This book, all of which has been written at the Front within sound of the German guns and for the most part within shell and rifle range, is an attempt to tell something of the manner of struggle that has gone on for months between the lines along the Western Front, and more especially of what lies behind and goes to the making of those curt and vague terms in the war communiqués. I think that our people at Home will be glad to know more, and ought to know more, of what these bald phrases may actually signify, when, in the other sense, we read ‘between the lines.’