Meeting Grace O’Malley, Ireland’s pirate queen

Reading time: 8 minutes

‘She had strongholds on her headlands

And brave galleys on the sea

And no warlike chief or Viking

E’er had bolder heart than she.’ 1

There are many surprising finds when one peers into the intriguing annals of piracy – none more so than the life of Grace O’Malley (Gráinne Ní Mhaille).

Born in 1530 to an Irish chieftain of the O’Malley’s of Murrisk, situated in a remote north-western corner of County Mayo, she forged a career in seafaring and piracy spanning over 40 years. Aside from this she was frequently active in regional politics and in native opposition in Connaught to encroaching English rule.

By Benjamin Trowbridge

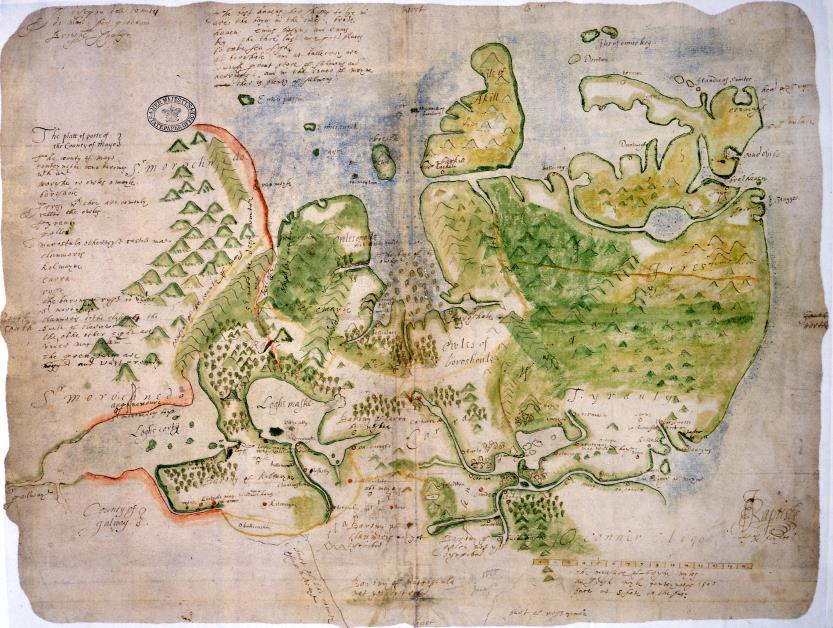

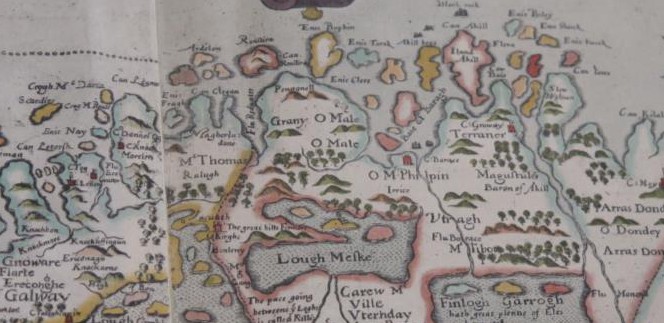

Map of County Mayo, 1585. The small island north of Clew bay in the centre of the map is Clare Island, where the O’Malley clan had their summer residence and which Grace used as a stronghold. The territory of the O’Malleys (‘Umhalls Ui Mhaille’) is marked on the left-hand edge of the bay: ‘owles omaile’ (catalogue reference: MPF 1/92)

Her remarkable life and career have not only been celebrated in numerous poems down the centuries, but also preserved for posterity in a surprising place: the official records of State Papers of the English crown. She features in the correspondence by English officials and also in records relating to her petitions and audience with Queen Elizabeth I.

In tribute to this remarkable woman, the details of her story revealed in these records should be shared.

Grace belonged to the O’Malley clan, who boasted a long tradition of seamanship. She would have been taught the art of seafaring, and been familiar with the seas around her home from childhood. Her marriages to powerful local clan strongmen Donal O’Flaherty and later Richard Burke would furnish her with the means she needed to embark on an extraordinary career.

From her strongholds on Clare Island and Carrickahowley (Rockfleet) in Clew bay, Grace would command her galleys to intercept ships travelling across the mouth of the bay, extorting levies for safe passage or plundering those foolish enough not to comply. Grace would also sail further afield either on peaceful trade missions or commanding raids against English and Irish enemies.

Many fables celebrating her courage and prowess have been captured in verse and song. For instance, the day after her son Theobald (known as Theobald of the Ships) was born on a return voyage from a trading mission in 1567, a Turkish corsair is said to have attacked their ship. In the midst of the battle she is said to have roused the courage of her men by firing a blunderbuss at the Turkish assailants and crying ‘take this load from unconsecrated hands!’ 2

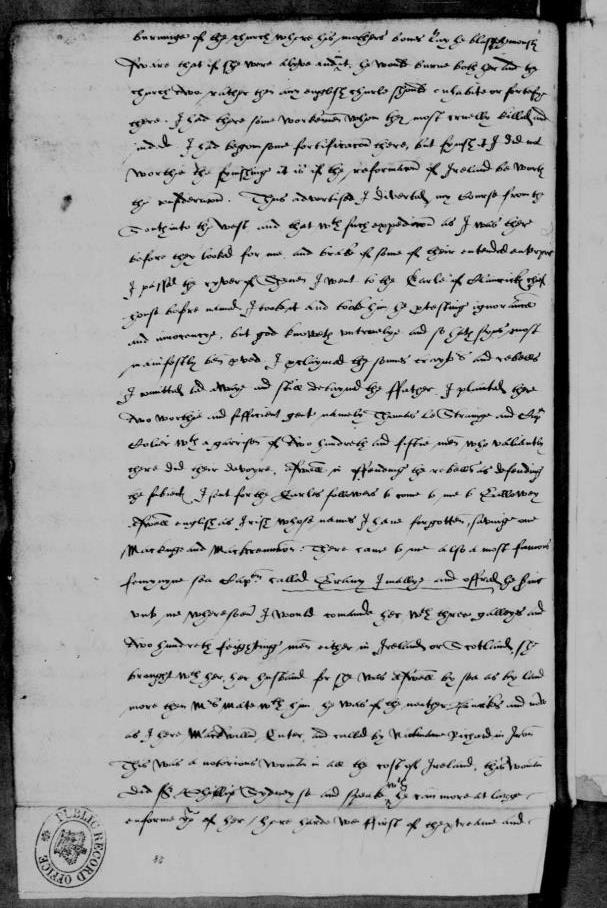

Sir Henry Sydney’s account to Walsingham of his conduct as Lord Deputy of Ireland; he recalls the meeting with Grace, and her name is underlined (catalogue reference: SP 12/159 f.27d)

Despite her general opposition to the English interference in the region, the fluidity of inter-clan politics meant that she offered the services of her galleys and men to the English crown in 1577. The Lord Deputy of Ireland, Sir Henry Sidney, reflects on this in a letter to the queen’s secretary Sir Francis Walsingham, six years later in 1583:

‘There came to me also a famous feminine sea captain called Grany Imallye and offered her services unto me, wheresoever I would command her with three galleys and 200 fighting men either to Scotland or Ireland….this was a notorious woman in all the coasts of Ireland.’

However Grace’s circumstances were to become increasingly difficult as the English administration tightened its hold on the Connaught region. At the hand of the ruthless new governor of Connaught, Sir Richard Bingham (appointed in 1584), Grace was deprived of much of her income as her cattle were confiscated and her ships seized.

Grace’s circumstances had become so desperate by 1593 that the pirate queen decided to dispatch a petition to Queen Elizabeth I, asking her for relief from a state of near poverty and for permission to attack ‘the Queen’s enemies’ for her maintenance. Her petition, although a plea for help, disguised an attempt to circumvent Bingham’s authority through favour with his sovereign.

In any case she received a reply to her entreaty which is perhaps the most interesting record produced from the administrative records of the English crown. The Queen sent Grace a set of 18 interrogatories (questions) to determine her family background, connections and the circumstances of her maintenance during her lifetime.

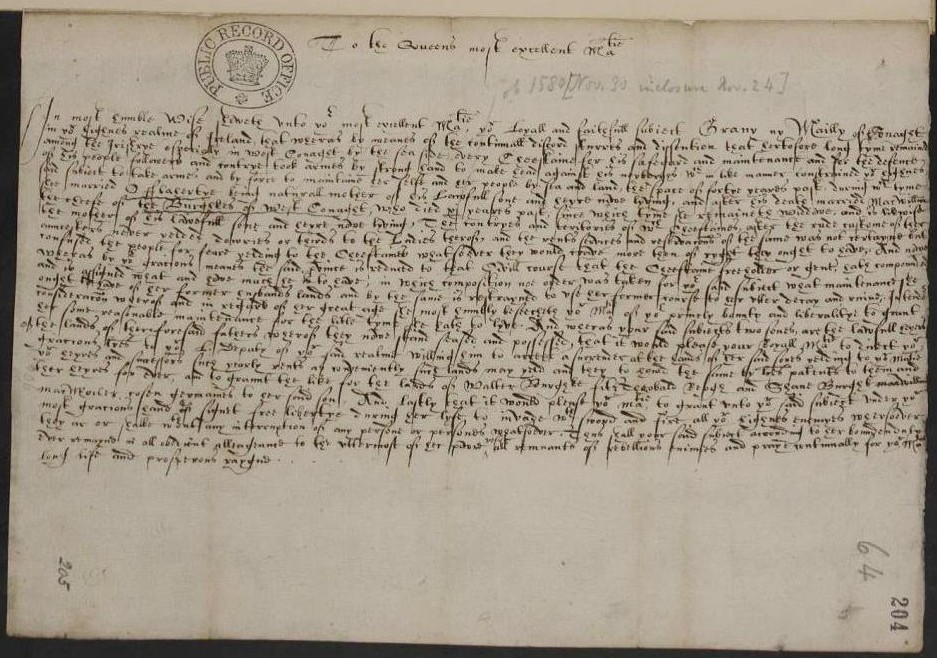

Grace’s petition requesting that the queen help settle her rights to sufficient maintenance, July 1593 (Catalogue reference: SP 63/170 f. 204)

Her answers reveal various details of her personal life including her marriages, family issues and personal circumstances. It gave Grace the opportunity to present her version of events as a victim of poverty and persecution with the intention that her words would induce Elizabeth’s sympathy. She did this with some skill, implying her actions of piracy were her only means of survival and the treatment she received at the hands of the overzealous Bingham callous and unjust.First page of the 18 interrogatories to be answered by Grace O’Malley (catalogue reference: SP 63/170 f. 201)A page giving Grace’s answers to four questions, with notes in the margin written by the queen’s secretary Sir Walter Burghley (catalogue reference: SP 63/170 f. 202)

In answer to one question she describes the ordeal of her arrest in 1586 at Bingham’s hand. She says he ’caused a new pair of gallows to be made for her last funerall wher shy thought to end her daies’ and only the intervention of her son in law Richard Burke saved her.

Her resolve to pursue justice for herself, spurred by the imprisonment of her son Theobald, led her to travel to London to seek audience with the queen.

Perspective of the River Thames by Jonas More, 1662. Grace would have probably witnessed a similar view of London in 1593 when seeking audience with Queen Elizabeth.

The encounter between Elizabeth and Grace O’Malley at Greenwich castle in September 1593 was a significant one as the first female sovereign of the ‘sceptred Isle’ met with the unconventional ‘pirate queen’ of the Irish seas.

Meeting between Grace O’Malley and Queen Elizabeth I at Greenwich Castle, September 1593. Illustration from Anthologia Hibernica, vol. 11, 1793.

Grace must have made a strong impression on Elizabeth: she subsequently granted Grace her requests on condition that she cease all rebellious activity against the crown.

Sadly Grace’s triumph in London was short-lived and although her son Theobald was reluctantly released, Bingham sought to undermine the terms of her recent agreement with Elizabeth. Two further petitions were sent by Grace to the Queen’s secretary in April and May of 1595 again beseeching support for the relief of her unjust impoverishment but no response is recorded (SP 63/179, ff. 75-76 and 77-78). Elizabeth was by this time preoccupied with the more urgent matter of quelling a major rebellion led by Hugh O’Neil, Earl of Tyrone.

The rebellion only served to impoverish Grace further, as county Mayo suffered devastation during the uprising. Her fleet was able to put to sea once again unchallenged, but Grace was in the twilight of her life and could no longer sail and rove the seas as she once did. She died sometime in 1603.

Her life had been forged and shaped by the sea and the wild shores of western Mayo and her life reflected a fierce devotion to independence as queen of the sea, queen of her clan, queen of Mayo. In the words of the final lines of Sir Samuel Ferguson’s poem, Grace O’Malley:

‘Such was the life the lady chose

Such choosing, we commend her.’ 3

Her name ‘Grany O Male’ lies over the territory top centre of the west coast of county Mayo and parts of Galway (catalogue reference: ZMAP 5/26)

This article was originally published in The National Archives.

Articles you may also be interested in

The Battle for Crete: Hard Fought

Reading time: 8 minutes

Wherever they fought in the Second World War, Australian troops acquitted themselves well. They escaped the clutches of the Afrika Korps in the Benghazi handicap and soon after helped hold back Rommel at the second battle of El Alamein. Even certain defeat couldn’t stop Australian troops, like in Crete, where they and their New Zealand counterparts fought a rearguard action that delayed the German war effort considerably.

The text of this article is republished from The National Archives and is licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.