Reading time: 7 minutes

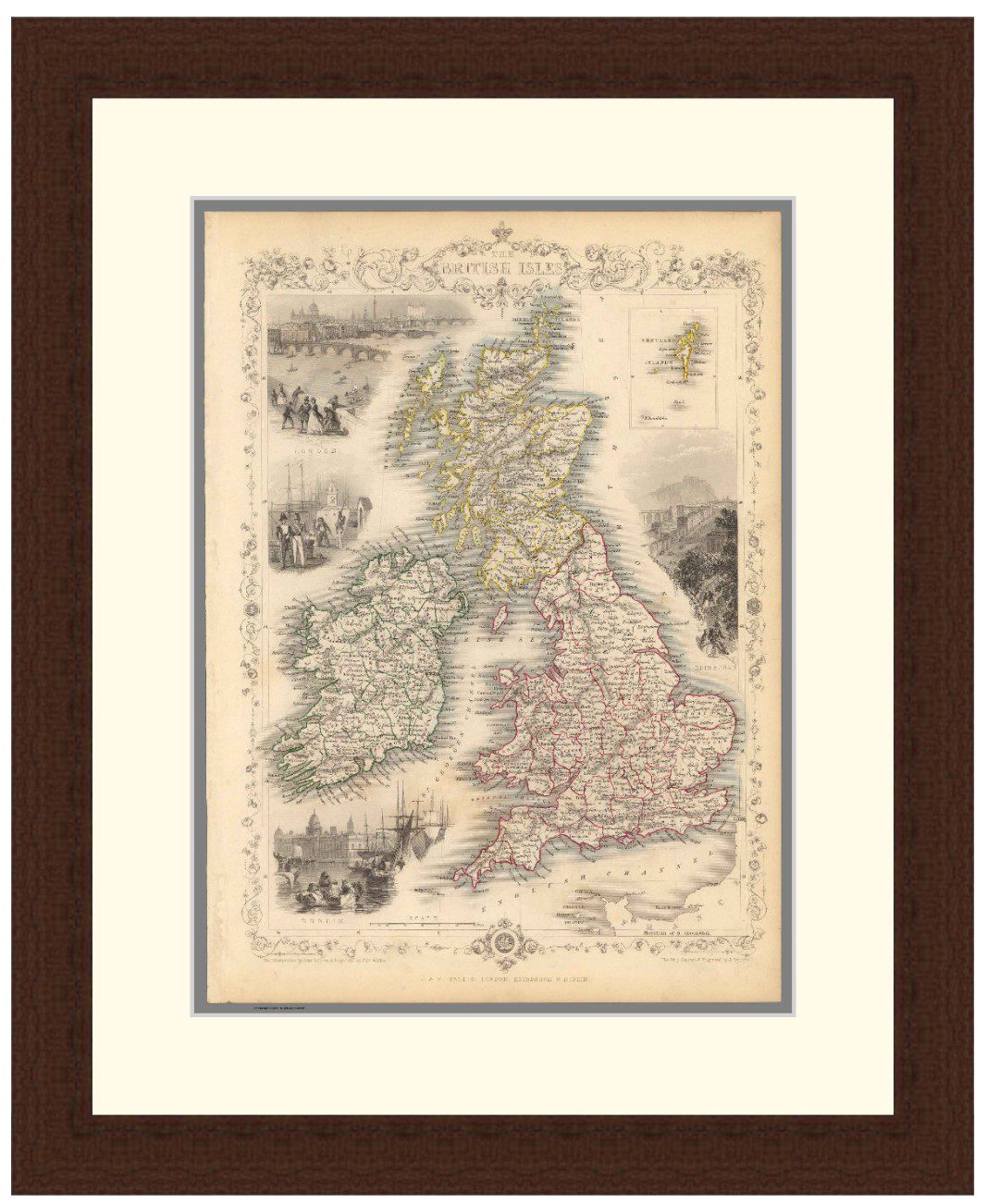

In almost every country in the modern world, although some more than others, various institutions, laws and social norms protect travellers. Yet the institutions such as the courts and the government, or the enforcing bodies such as the police, have not always existed.

In fact, they have not existed in their current form for very long at all.

Yet even in a world without an established police force or constant communication methods, guests and travellers in Medieval England would still find themselves protected. By the medieval period, England had built up a network of social contracts and common law to protect travellers.

But how? Here is a brief history of guest rights in Medieval England, including how they came into being and how they protected travellers.

Anglo-Saxon Guest Rights and Attitudes Towards Hospitality

Explored in great detail by Dr Tom Lambert, the position of the stranger or guest in Anglo-Saxon society was a precarious one.

On the one hand, locals were rightfully wary of strangers – Anglo-Saxon law and justice relied heavily on retribution, something not easily administered if the offending party had no connections and could simply disappear into the countryside.

Hence it was common for strangers to be treated with caution, with a passage in 7th century law from both Kent and Wessex reading “If a stranger or man from afar quits the road and neither shouts nor blows a horn, he shall be assumed to be a thief and as such may be either slain or put to ransom”.

Yet just as locals had extreme rights in the eyes of the law to protect themselves from possible thieves, strangers who made themselves known would be equally protected by law:

“If any attempt is made to deprive a … stranger of either his goods or his life, the king (or the earl of the region) and the bishop of the diocese shall act as his kinsmen and protectors, unless he has some other. And such compensation as is due shall promptly be paid to Christ and the king according to the nature of the offence; or the king … shall avenge the offence” – a passage from an early 11th Century Text dictating Anglo-Saxon Law.

As the heart of Anglo-Saxon law lay with community bonds and roots, it became the responsibility of local men of authority such as the bishop or the Earl to take up the position of any traveller’s kin.

Through this form of law, Anglo-Saxon England enshrined the protections of travellers and guests as they travelled through England, an early codification of traditions that would quickly develop into a complicated and established set of precedents for protecting guests and travellers in England.

Medieval England’s Religious Foundations for Hospitality

While the Anglo-Saxons were not originally Christian, by the 11th Century England’s conversion to Christianity was well on the way.

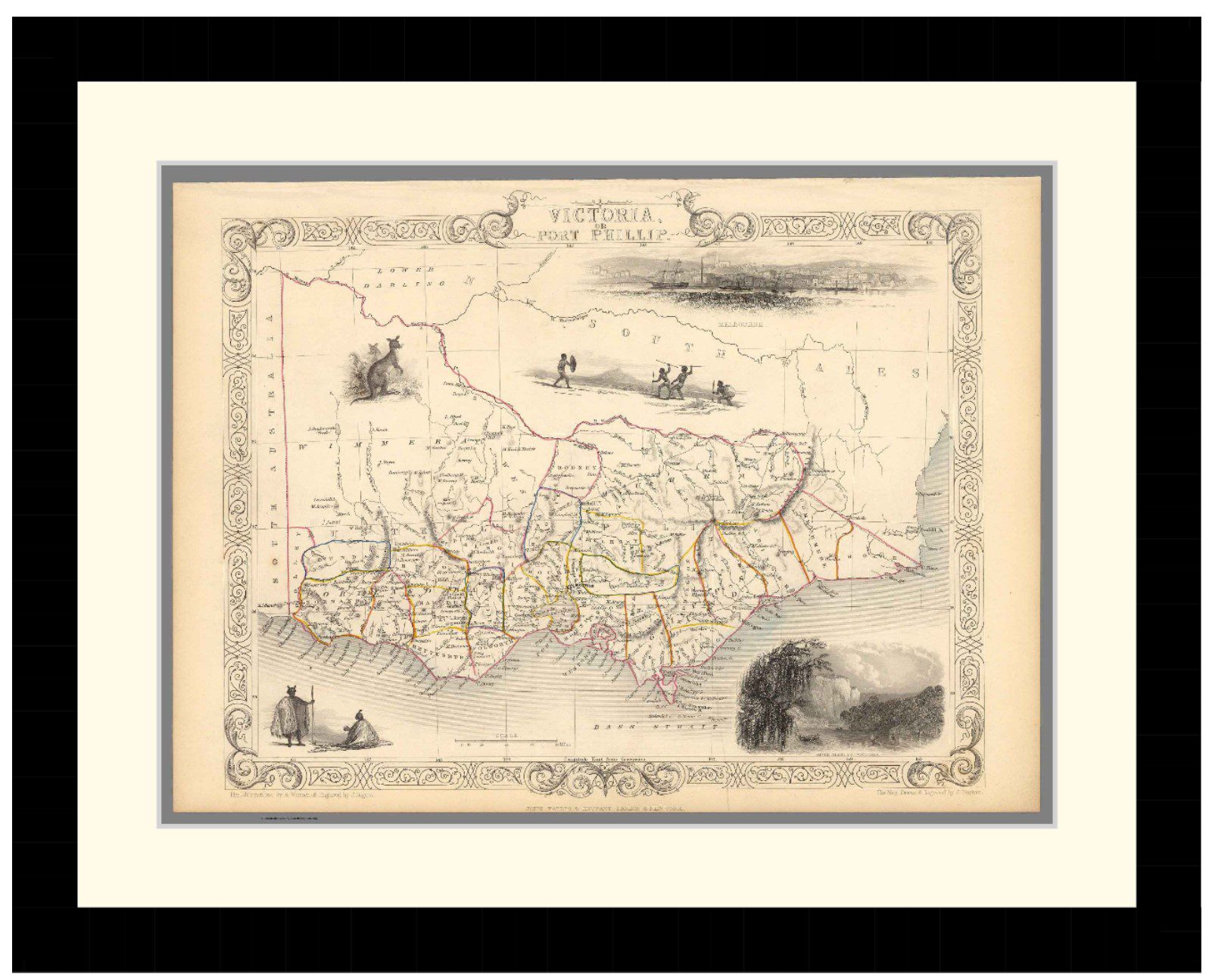

As England moved from the Norman invasion into the Medieval period, Christianity and specifically the church played an ever-increasingly important role in hosting and protecting guests, with monasteries beginning to form the backbone of England’s domestic travelling routes.

Biblical teachings, particularly passages from the New Testament, reinforced the Anglo-Saxon tradition of protecting the guest, ensuring that any religious building was ready to take in travellers.

“All who arrive as guests are to be welcomed like Christ, for he is going to say, ‘I was a stranger and you welcomed me.” (Rule of Saint Benedict 53:1)

Following these teachings, while other forms of hospitality existed such as Alehouses and Inns, it was Christian buildings, mostly monasteries, which became England’s hub of guesthouses, obligated by God to host any honest traveller from Lords and Ladies to the lost and homeless.

A Longer World History of Hospitality

It is important to remember that neither England nor Christianity were unique in upholding hospitality customs and laws.

The Ancient Greeks had their concept of Xenia, the divine right for guests and the divine duty of the host, and similarly the Romans, Islamic cultures, and many others from across time and the world had their own forms of hospitality rules.

While no two cultures are the same, the social contract of protecting your guests remains a constant foundation for all successful civilizations across history.

Medieval England’s Social Contract – The Rules of Hospitality

The polite or normal length of stay at any such religious house was two days and two nights, however with no set rules this custom was often abused, especially by those with influence and power.

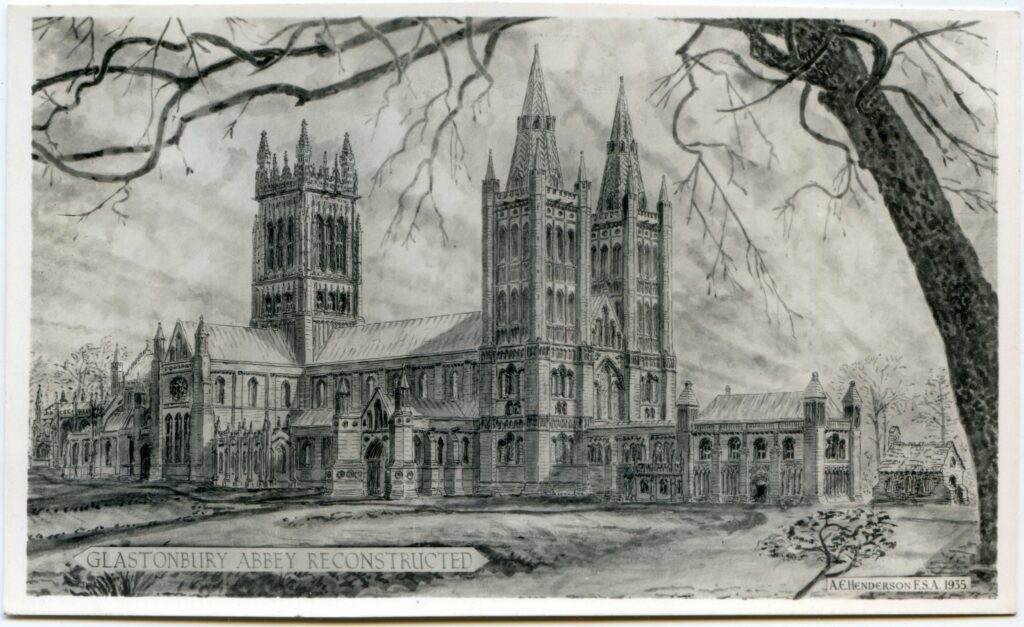

Larger buildings could of course expect to more often host grander guests, such as Worcester Cathedral’s long history of hosting Dukes and noblemen. Yet no matter the grandness of the building, all travellers were welcome.

As Historian Edwards explores, all from prince to peasant were welcome, citing Glastonbury’s guesthouse rules specifically, noting that “none were commanded to depart, if they were orderly and of good behaviour”.

While it was the Church that often took in strangers and weary travellers across the country, the rules of hospitality were universal, applying to any host. As English Common Law developed, the innkeeper became obliged by law to accept all those who apply for accommodation (within reason), with the position of innkeeper becoming a position of public duty.

The Importance of Providing Hospitality – Communication Flow

Aside from influential guests, the arrival of merchants, minstrels, and other travellers would often be a local community’s only access to news of the outside world.

On a fundamental level, maintaining good hospitality standards ensured a local community remained connected to the wider country. A town, village, or city that had a poor level of hospitality would naturally spread via word of mouth, deterring new visitors and decreasing the amount of news, trade, and entertainment.

The Breaking of Guest Rights

Despite all our gadgets and societal changes, the societal norms of Medieval England, just like ours today, were not unbreakable.

For power, any rule can be broken, and where there was sufficient reason from the host to break the rules of hospitality, the host often did.

One of the most famous examples include the “black dinner”, where in Scotland the 6th Earl of Douglas, a teen set to be a major player in Scottish politics, was invited to dine at Edinburgh Castle, only to be summarily executed after the meal by William Crichton, who foresaw a threat to his position in the 6th Earl of Douglas.

How Understanding Medieval Hospitality Helps Us Conceptualise the Past

Throughout the study of history, there are thousands of rules, terms, and “societal norms” that can be complicated to understand. When do these rules apply? How were they determined, and who determined them?

By looking at the Medieval rules surrounding hospitality, and comparing them to our own, we can better understand our ancestors’ societies.

While hospitality in Medieval England was often underpinned by a fluctuating system of common law and Kingly decrees, its application depended more on mutual understanding and specific circumstances.

Just as no one person dictated the current English tradition of offering guests a cup of tea, the rules of hospitality in Medieval England were not set in stone by some governing body, nor were they unbreakable. They were a fluid and changing set of societal standards that were slowly incorporated into English common law as it evolved alongside the institution of the Church.

Podcasts about Medieval Hospitality

Articles you may also like

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.