Reading time: 10 minutes

Keith was 25 years old when he enlisted with the 2/11th Battalion in Kalgoorlie, in November 1939. He had been working as a bank clerk with the Commonwealth Bank before the war, his skills in organisation and administration may have been part of why he was selected for officer training.

He was promoted to Lieutenant in May 1940 while still in Australia. After a short period of leave he embarked for the Middle East in June. On arrival the unit threw itself into intensive training. During this time he visited Jerusalem, exploring as many tourist sites as he could get to, and buying and sending home souvenirs, including what he called a ‘magic carpet’! The Battalion were ‘not

considered hard enough yet’, so they were sent on a 70 mile (112km) march over a five day period. Keith was pleased with his performance, he ‘fully expected to be stiff – but I

feel right in the pink. That was my first march of any distance since the Rockingham bivouac from Claremont.’ The unit took time out from their training for swimming, at Gaza and Jaffa, and to watch movies.

Keith spent a month on a mortar training course in near Tel-Aviv, where he commented on the number of refugees fleeing Nazi persecution of Jews in Europe. He spent a lot of time swimming, as well as looking for places that he knew from the Bible. He rejoined his unit near Jerusalem at the end of September. In a sign of his increasing skill in military arts, Lt. Dundas was made Assistant Adjutant and assigned responsibility for the transport of all the Battalion’s stores and equipment. He also wrote many of the Battalion routine orders, dealing with sick parades, parcels from home, issue of rations and clothing.

It is interesting how Keith managed to keep his family informed in a ‘coded’ way that avoided the letter censor’s disapproval. In October he was preparing the unit to move to Egypt and into combat. This was classified information that he wasn’t permitted to include in his letters. In a letter home he wrote ‘Next week everyone has to have the option of taking a day’s leave. You can draw your own conclusions from that. Anyhow, present indications are that preparations for Xmas dinner here can be cancelled. What Xmas dinner we have will probably be very sandy.’

By early November he followed up with this passage in a letter ‘It looks as though we’re going to have that ‘special’ Christmas dinner I spoke of. My mail may not perhaps be so regular in future, but I’ll write as often as circumstances permit. Next time I do write I may have a few points of interest to mention. Doreen may know the poem about the Arabs & one of Tennyson’s mentions ‘new faces’ amongst other things.’

Reading his letters you are reminded that normal life continued even when a soldier was stationed overseas. Many of his letters talk of news from home, as well as dealing with the minutiae of life. This is well illustrated by Keith’s correspondence with the Bankers Institute, explaining that he was overseas in the AIF and wouldn’t be paying his membership until he returned!

Keith cared for the welfare of the soldiers under his command. One of his soldiers was ‘very worried man – he hasn’t had any mail since he left Australia.’ Keith realised how disheartening it was ‘seeing others getting mail & not receiving any oneself’. Keith asked his father to contact the man’s next of kin to confirm that she was correctly addressing mail to him, as well as get in touch with officer in charge of mail at Swan Barracks, Perth, the unit’s home.

In November the 2/11th Battalion moved from Palestine to Egypt in advance of engaging the Italians in combat near the Egyptian-Libyan border. They were based near Alexandria, Keith include the clue that ‘there’s an old Roman lighthouse nearby’ to try to let his family know where he was.

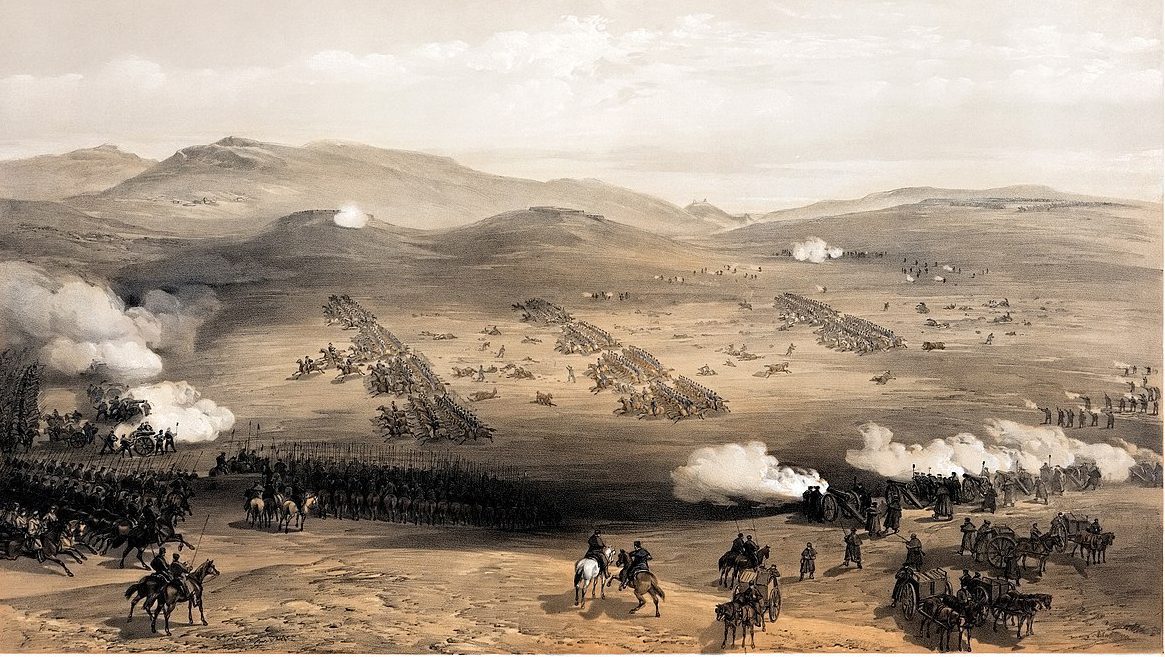

In January 1941 Keith took part in the Battle of Bardia, where he was attached to 2 Platoon, A Company. The unit arrived behind schedule and had to run to keep up with the creeping artillery barrage. Later in the month they were fighting around Tobruk and Derna, and then Benghazi the following month.

He embarked for Greece along with the rest of the 2/11th Battalion in April 1941. The battalion fought at the Battle of Brallos Pass, a hectic, one-day battle on 24th April, 1941, fought 200 kilometres northwest of Athens. Keith’s C Company held the key terrain north of the village of Brallos, pinning down the German 55th Motorcycle Battalion that was advancing up the valley towards them, before breaking contact and withdrawing in good order once their job was done.

Visit the Brallos Pass battlefield

The 2/11th Battalion was evacuated from mainland Greece to Crete.

Keith was a platoon commander in the force defending Rethimno, in North-central Crete. He saw 11 days of continuous fighting in which the Australian forces successfully fought off the German paratroopers who had landed around Rethimno, attempting to capture the airfield. However, the Allied forces further west had been defeated, and a large German force reached Rethimno, overwhelming the already depleted and exhausted Australian troops. Lt Keith Dundas commanded the Anti-Aircraft Platoon during this battle, which had been placed under C Company’s command. This unit was situated in the hills overlooking the airfield, the main German objective. As the Germans pushed through the Australian defences Keith ran from position to position to give his soldiers their orders to fall back.

I watched… its leap-frogging withdrawal with magnificent coolness and precision, one section blazing away at the Germans on the hill and across the road while the other streaked past it to the next patch of shrubbery to repeat the process.

Lt Colonel Ralph Honner

Visit the Rethimno battlefield

Keith was lightly wounded by shrapnel in the leg during this final action and was captured along with 548 other soldiers of the 2/11th Battalion. The next two months were spent in POW transit camps in Crete and Greece. In this time his wound turned septic. On arrival at Oflag X-C his wound was treated and he recovered.

Throughout the period of his imprisonment the rations he received from his German captors were ‘poor and inadequate’ but were supplemented by irregular arrival of Red Cross parcels.

Captured on Crete on the 30th May 1941, his father, Rev. David John Campbell Dundas of 102 Angove St, North Perth received a telegram notifying that his son was missing on the 11th of June, 1941. He was among the 850 Western Australians listed as missing in the 19th of June 1941 edition of The Daily News, Perth. This very worrying news improved slightly when on the 25th June 1941 Keith’s status was changed to Missing Believed Prisoner, which was confirmed on the 8th July.

Keith was detained at Oflag X-C, a German prisoner-of-war camp for officers in Lübeck in northern Germany. This camp was opened in June 1940 for French officers captured during the Battle of France, from June 1941 British and Commonwealth officers captured in Greece, Crete and North African were added to their number.

Keith was held here until January 1942, when he was moved to Oflag VI-B, near Warburg in central Germany. British officer Eric Foster, who was also held in the camp, as well as several other POW camps, described it as ‘a very, very bad camp indeed’. Keith arrived at the camp shortly after an escape attempt by Flt Lt Peter Stevens RAFVR. He and a dozen other Allied POWs disguised themselves as a German Unteroffizier, leading a party of orderlies and guards complete with dummy rifles. They made two attempts to escape, but were unsuccessful.

Visit Oflag VI-B

Keith was at the camp during Operation Olympia, also known as the Warburg Wire Job, a mass escape attempt. British officer Major B.D. Skelton Ginn disabled the perimeter floodlights and 41 prisoners carrying scaling ladders made from bed slats rushed to the barbed-wire fence and clambered over. 41 POWs were involved, 28 escaped the camp, and three of those made it to England.

After this escape attempt the British and Commonwealth officers, including Keith, were transferred to Oflag VII-B, in Eichstätt, Bavaria. This camp was also the site of a mass escape attempt while Keith was there, this time involving tunnelling. Seven Australians took part. Lieutenants Clive Dieppe and George Bolding were engaged in soil dispersal. Captain Rex Baxter and Lieutenants Jack Champ and Mark Howard were part of the digging teams. Lieutenant Jack Millett, from Western Australia, was one of the prisoners who mass-produced maps for the escape. While Keith isn’t named, it would seem likely that he assisted with escape preparations. Was he part of the group helping his fellow Western Australian produce maps? The tunnel was completed in May, and on the night of 3/4th June 1943 sixty-five men escaped. Most of them headed south, towards Switzerland, sleeping by day and travelling by night, but eventually all 65 were recaptured.

This camp was the site of a tragedy as the U.S. Army approached. On 14th April 1945, the officers were marched out of the camp. A short distance from the camp the column was attacked by American aircraft, who mistook it for a formation of German troops. Fourteen POW officers were killed and 46 were wounded. In 2003 a memorial plaque was erected by local German authorities at the site. After the Allied forces reached his POW camp he was transported to England, where he was billeted at Eastbourne for rest, recuperation and medical treatment. He was granted leave and free train travel around the UK, prior to embarking for Australia. He was discharged on the 27th of September 1945. Keith is commemorated on the Australian Ex-Prisoners of War Memorial at Ballarat, Victoria.

Visit the Australian Ex-Prisoners of War Memorial

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 54

The History Guild Weekly History Quiz.See how your history knowledge stacks up. Have an idea for a question? Submit it here and we’ll include it in a future quiz!

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.