Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

Just five days before Christmas, in the early hours of Monday December 20, 1915, the last Anzac troops left Gallipoli in what Australian historian Joan Beaumont called an “elaborate game of deception”.

Self-firing guns were rigged to take pot-shots and camp fires lit to give the impression of there being more soldiers than there were.

The Australians and New Zealanders even played a game of cricket to show the Ottomans they were there for the duration. Yet by around 4.30am all had gone.

By Julia Horne, University of Sydney.

Not one life was lost, an Allied triumph of sorts. Yet most Australians celebrate Gallipoli as a purely Australian achievement, usually without acknowledging that Australians were a minority of Allied troops fighting there.

Gallipoli was mostly a site of significant Allied loss. There were more than 141,000 causalities, of which more than 44,000 men died – including 8,709 Australians, with similar losses amongst the Ottomans. In our Australian obsession with Gallipoli as a national legend, we often lose sight of its universal meaning as a failure, a defeat for the Allies that came at great cost in human lives.

For those who were there one hundred years ago, Gallipoli was not the stuff of legend that it later became, but a site of regret and despair, something shrouded in defeat rather than retrospective triumph.

The diaries and letters of soldiers reveal how these complicated sentiments were not easily reconciled to the meticulous and orderly removal of 41,724 Anzac troops.

They provide insight into war and the soldiers who served, revealing the stresses and strains of collective failure before the silence descended and the legend emerged. Such unreconciled sentiments later contributed to feelings of profound alienation.

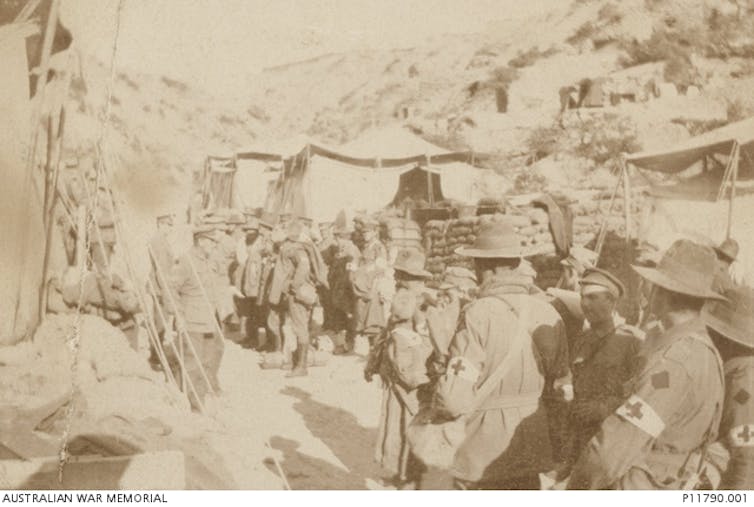

After eight months of fighting and making do in stinking trenches, shivering with the onset of a fierce winter, watching their wounded compatriots screaming with pain or being blown to bits, and having to bury many in mass graves, finally the word spread of their evacuation.

Captain Francis Coen, who later died in action at Pozieres, initially saw the sense in leaving Gallipoli. He understood the rationale of moving strength to where chances for success were higher. In a diary entry on December 16, written as a letter to his mother, he lamented the loss as he looked to the future:

I understand I shall be one of the last to withdraw. I do, honestly speaking, sincerely hope so, as I wish to see the last of the affair. Let us hope we shall be successful. Many brave lives have already been sacrificed in this blunder.

It is bitter to leave so many of our dead heroes in their lonely graves in this foreign soil. But necessity is imperative. We can do no good by staying here.

Then two days later this stoicism gave way to raw sentiment:

A feeling of great disappointment and depression has seized me because of this evacuation. It is one of the “downs” of the war and we must accept it.

The 26 year old Captain Eric Mortley Fisher, who had served as a medical officer in a dugout at Gallipoli since August 1915, expressed similar emotions:

Well, one day we heard definitely that the place was to be evacuated & all became sore, blue & depressed. Personally for a couple of days I walked about or sat & played patience & couldn’t be bothered taking cover, hoping I would get shot.

It sounds foolish now, but at the time my mental condition was not quite normal I’m afraid.

The uncertainty was great and in preparation for the worst, they made their farewells.

… the suspense and strain on the last few days was terrible. Every minute you expected the Turk to drop to it that we were evacuating (& not landing more troops as he evidently thought) and plaster the beaches with shells & the more you discussed it the worst it looked.

They packed up the ammunition, mules, carts, stores including the rum, wine and brandy, and destroyed whatever could not be taken including mounds of socks, blankets and equipment.

Then one night we got orders to leave. It was a simple process & consisted of turning out the lamp & walking out with a few things in a pack & my blanket & leaving everything else.

They muffled their boots with socks and wrapped them in blankets and sandbags, then as silently as they could:

marched to the wharf with the shells screaming over us all the time & got there safely. After a short wait we embarked on a barge, but for some reason waited an hour & a half at the wharf getting stone cold & watching the shells burst over the water just where we had to go. This sort of thing was not exactly soothing to the nerves …

At last we got word to move and strange to say the shells stopped and we heard no more bullets while going out to the ship & got safely on board. I found an empty seat and went to sleep at once.

In some ways, sleeping upright, exhausted, was a fitting end to the Gallipoli campaign, a lingering metaphor of a semi-bewildered and war-wearied soldier being shipped off to another theatre of war.

It reminds us that Gallipoli was a symbol of war; not in the ways usually celebrated in Australia on April 25, but of the human vulnerabilities and frailties of soldiers.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation.

Articles you may also like

The Somme: The German perspective

By Dr Robert T. Foley. How do Germans view the Battle of The Somme? This article explores reactions to the most famous battle of the First World War. Shortly after daybreak on 1 July 1916, around 100,000 troops of Sir Henry Rawlinson’s 5th Army left their trenches and advanced on the German trenches across no-man’s-land. […]

How Romania’s WW1 Gamble Paid Off Spectacularly

Reading time: 6 minutes

The Great War was a major turning point for virtually all European countries, but not too many of them enjoyed a positive outcome. Although it took two years for Romania to enter the war and another two for the conflict to reach a conclusion, the result was an unlikely unification of its historical lands and the beginning of the most prosperous period in the nation’s history.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.