When the infamous Zong trial began in 1783, it laid bare the toxic relationship between finance and slavery. It was an unusual and distressing insurance claim – concerning a massacre of 133 captives, thrown overboard the Zong slave ship.

By Philip Roscoe, University of St Andrews.

The slave trade pioneered a new kind of finance, secured on the bodies of the powerless. Today, the arcane products of high finance, targeting the poor and troubled as profit opportunities for the already-rich, still bear that deep unfairness.

The Gregsons, claimants in the Zong trial, were merchant princes of 18th century Liverpool, a city that had quickly grown to be one of the world’s leading commercial capitals. The grandiose Liverpool Exchange building, opened in 1754, boasted of the city’s commercial success and the source of its money, its friezes decorated with carvings of African heads.

But Liverpool’s wealth also stemmed from its innovations in finance. The great slave merchants were also bankers and insurers, pioneers in what we today call financialisation – they transformed human lives into profit-bearing opportunities.

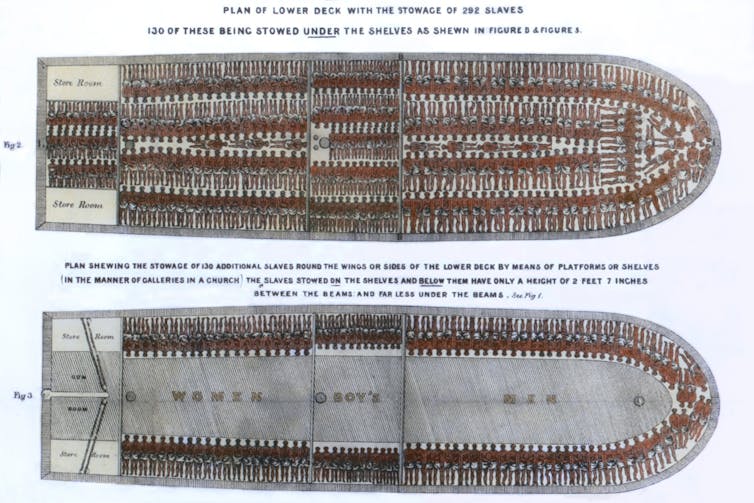

From the point of view of merchants, the Atlantic trade was slow, unreliable and risky. Ships were threatened by disease, by poor weather, and by the constant threat of insurrection. To speed up the flow of money, merchants began to issue credit notes that could travel swiftly and safely across the ocean.

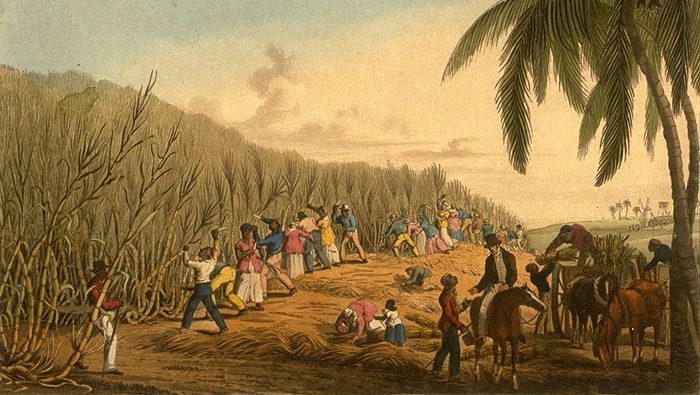

Slaves would be purchased in Britain’s African colonies and transported to the Americas where they were sold at auction. The merchant’s agent would take the money received and rather than investing it in commodities like sugar or cotton to be sent back to Liverpool, they would send a bill of exchange – a credit note for the sum plus interest – across the Atlantic.

The bill of exchange could be cashed at a discount at one of the many banking houses in the city, or replaced by another, again at a discount, to be dispatched to Africa in payment for more human chattels. Credit flowed swiftly, cleanly and profitably.

Obscenely novel

This evolution of private credit did not originate in Liverpool. It had underpinned the Florentine banking dynasties of the 15th century and gave rise to money as we know it now.

The obscene novelty of the slavers’ banking system was that this financial value was secured on human bodies. The same practices continued on the plantations, where the bodies of slaves were used as collateral on loans allowing the expansion of estates and the acquisition of yet more productive bodies. The slaves were exploited twice: their freedom and labour stolen from them, their captured “economic value” leveraged by cutting edge financial instruments.

The Liverpool merchants also pioneered the use of insurance as a means of guaranteeing the financial value of the their commodities. The slavers had long recognised that the only way to survive the occasional total losses that expeditions incurred was to gather together in syndicates and share the risk.

So when the captain of the Zong realised he was unlikely to land his cargo of sickening and malnourished slaves, he ordered 133 souls to be thrown overboard. The perverse legal logic was that if part of the cargo had to be jettisoned to save the ship, it would be covered by the insurance.

These bodies-as-financial-commodities had only speculative value. Insurance made it real and bankable. This was true in 18th century Liverpool and it remains so in 21st century Wall Street.

Financialisation today

Financialisation has since taken many forms, but basic elements remain the same. It is based on uneven power relations that capture future individual obligations and make them saleable. The contracts underlying the 2008 credit crisis, for example, turned future mortgage payments into tradeable financial securities with actual present value.

For those issuing the bonds, the profit was risk free. The risk was borne by predominantly poor Americans, whose adverse credit ratings and lack of financial skills made them easy prey for the issuers of mortgages so constructed as to lock them into economic bondage. These people were disproportionately black, Latino or migrant.

Insurance played a part here, solidifying the speculative value of investments to the benefit of traders. And when the bubble finally burst governments stepped in to maintain this system, the US Federal Reserve supporting giant insurer AIG to the tune of US$182 billion (£139 billion) while many people lost their homes.

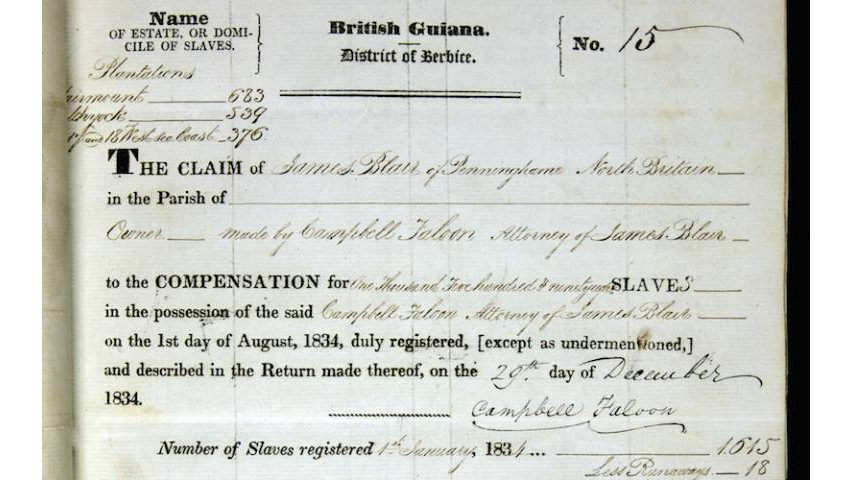

The credit crisis bailout is eerily reminiscent of another. By the time of abolition slave ownership was so embedded in British society that the government was forced to compensate individual owners for the loss of their capital – it required an enormous loan that taxpayers only finished paying off in 2015.

I’m not saying that bankers today are like slave traders. But I am saying that contemporary finance is still riddled with regimes of dominance and exploitation at work.

Take contemporary philanthrocapitalism, where finance seeks to do good while also benefiting investors. Novel financial instruments position social problems as an opportunity for profit. The bodies of prisoners, for example, become implicated in schemes to prevent recidivism with personal character reform the trigger for investment payouts.

Schemes such as this make social problems the responsibility of individuals and ignore the structural relations of austerity that lie behind them. Finance wins twice, praised for solving the very same problems that it has benefited from creating.