Reading time: 5 minutes

In the shadow of the pyramids of Giza, lie the tombs of the courtiers and officials of the kings buried in the far greater structures. These men and women were the ones responsible for building the pyramids: the architects, military men, priests, and high-ranking state administrators. The latter were the ones who ran the country and were in charge of making sure that its finances were healthy enough to construct these monumental royal tombs that would, they hoped, outlast eternity.

In the Old Kingdom, a period that stretches over roughly 500 years (2686–2181 BC), the economy was primarily agrarian and so heavily reliant on the Nile. The river inundated the fields along its banks and provided fertile silt. It also enabled the transport of commodities across the country.

By Andreas Winkler, University of Oxford

Research suggests that the majority of the cultivated soils were part of large estates that were under the control of the crown, various temples, and wealthy estate owners, who were usually royal officials.

Such estates should not be regarded as entirely separate units but as intertwined. They were often part of the same redistribution network, ultimately responded to the king, and were, to a certain extent, reliant on the central state administration. This system may have also involved both formal and informal networks of redistribution and favours. The society of this period has been likened to a feudal system, such as that found in medieval Europe.

A complex tax system

In general, the estates, together with towns, were the basic units of economic and societal organisation. The sources suggest that the crown did not tax individuals, such as farmers, since the administration does not seem to have been able to handle the detail of such a task on a countrywide basis. Instead, it burdened the heads of these estates, who were personally liable to deliver revenues to the coffers of the crown, and to ensure that the domain, which they oversaw, delivered the expected surplus. Failure to do so could result in physical punishment.

In order to calculate the revenues and thus how much tax would be paid to the royal administration, the crown conducted periodic censuses. Individuals were not counted but rather taxable goods, such as cattle, sheep and goats. It is also clear that other products were collected, such as fabrics and other types of handiwork.

The taxes that the state levied were amassed in granaries and treasuries and then redistributed back to estates or to building projects of various sorts. This could be the construction of a royal tomb and the upkeep of its mortuary cult. Evidence for how such a royal mortuary cult was run has been found at Abusir, just outside modern Cairo. These texts enlighten historians about the daily doings and dealings of the priests, and how the worship of the deceased king was connected to the royal administration and various other temples estates.

Smooth operation

The estate chiefs were wealthy, but they did work for it. They were responsible for ensuring that their estates ran smoothly and that their corvée workforce was fed, dressed, and provided shelter. In the pyramid towns at Giza, they were even fed prime beef, fish and beer. This may have been one of the perks of the corvée workforce, which was summoned from various estates across the country for royal monumental constructions.

From Abydos in Upper Egypt, an inscription belonging to Weni, a judge and military commander, indicates that soldiers were conscripted from the same pool of people as the corvée workers. They would take part in various state-sponsored expeditions to mineral-rich lands bordering ancient Egypt. Raw materials like copper and hard wood (which was needed for the larger construction projects) would be brought back to Egypt. Luxury items were also brought to the Nile Valley, including exotic animals, plants, and people for the amusement of the court. The latter were certainly slaves.

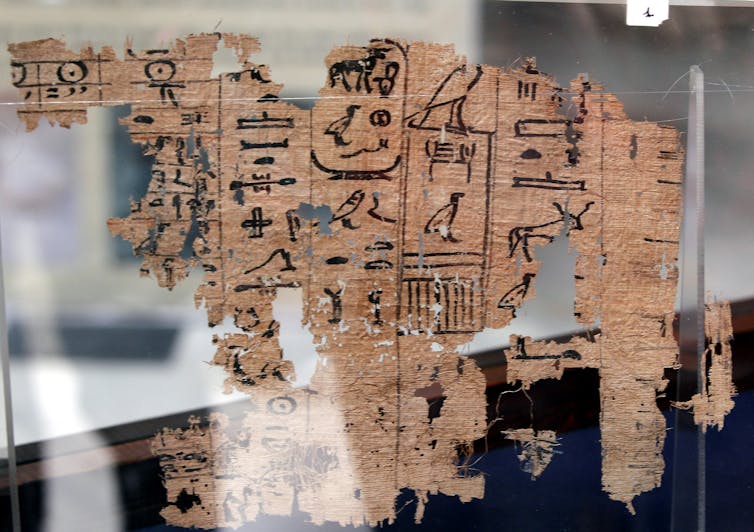

At Wadi al Jarf by the Red Sea coast, which functioned as a port during the Old Kingdom, papyri documents from the reign of Khufu have been found. These texts contain a log of a skipper called Merer, and his activity transporting men and goods in and out of Egypt. The papers also tell us how he and his 40 men participated in the construction work of the pyramid by shipping stone from quarries to the construction site of the Great Pyramid at Giza.

It is hypothesised that these projects refined the administrative apparatus and fuelled the Egyptian economy. Merer, as well as the estate officials, were working for the royal construction department that was responsible for all major building work in the country and probably also for erecting the large pyramids at Giza and Sakkara to the South.

The workforce – whether a royal administrator or a manual labourer dragging stone at the construction site – provided services to the crown. In turn, the crown reciprocated the labour by redistributing food and other commodities to the work-leaders, who themselves circulated it further down the social ladder. But it was only the people higher up in the hierarchies that could also be rewarded with a state-sponsored mortuary cult next to the king’s tomb.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about the Pyramids of Egypt

Articles you may also like

How the Thirty Years War Affected Germany

Reading time: 4 minutes

The Thirty Years War (1618-1648) was a brutal conflict that saw most major European powers use Germany as a battleground to sort out their assorted dynastic, religious, economic and territorial issues. The toll this took on the country was massive, and reverberated for long after; let’s take a look at some of the damage it did.

Law enforcement in medieval England

Reading time: 6 minutes

The middle ages are often associated with lawlessness and brutality. Along with knights in shining armour, the images we often associate with the period are torture devices like the rack, or public punishment like the stocks. Was that really how law and order were maintained in the Middle Ages?

Deceptive Ineptitude: German Spies in WW2 Britain

DECEPTIVE INEPTITUDE: GERMAN SPIES IN WW2 BRITAIN Operation Lena, the German espionage operation in Britain, turned out to be one of the least successful spy missions of World War 2. By Madison Moulton Plotting an invasion of the United Kingdom in 1940 – codenamed Operation Sea Lion – the Nazis sent spies to gather intelligence […]

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.