HOW CYPRUS BECAME DIVIDED

Reading time: 8 minutes

Cyprus is a country that on paper is whole, but in reality is divided into several parts. Greeks, Turks, Cypriots and the United Kingdom have all staked claims on the island, with the UN in the middle, doing their best to maintain the peace. But what made Cyprus into an island of lines? The answer is, as it usually is, extremely complicated, but we’ll go over the main points in this article.

By Fergus O’Sullivan

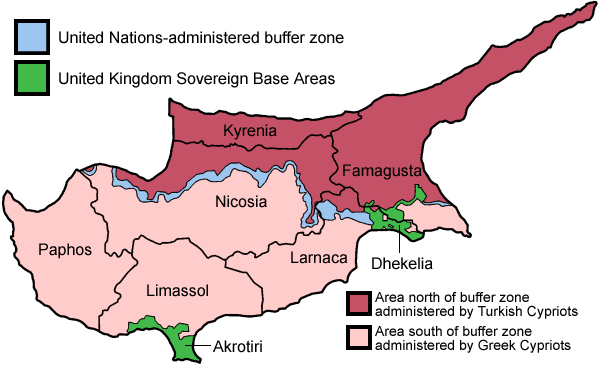

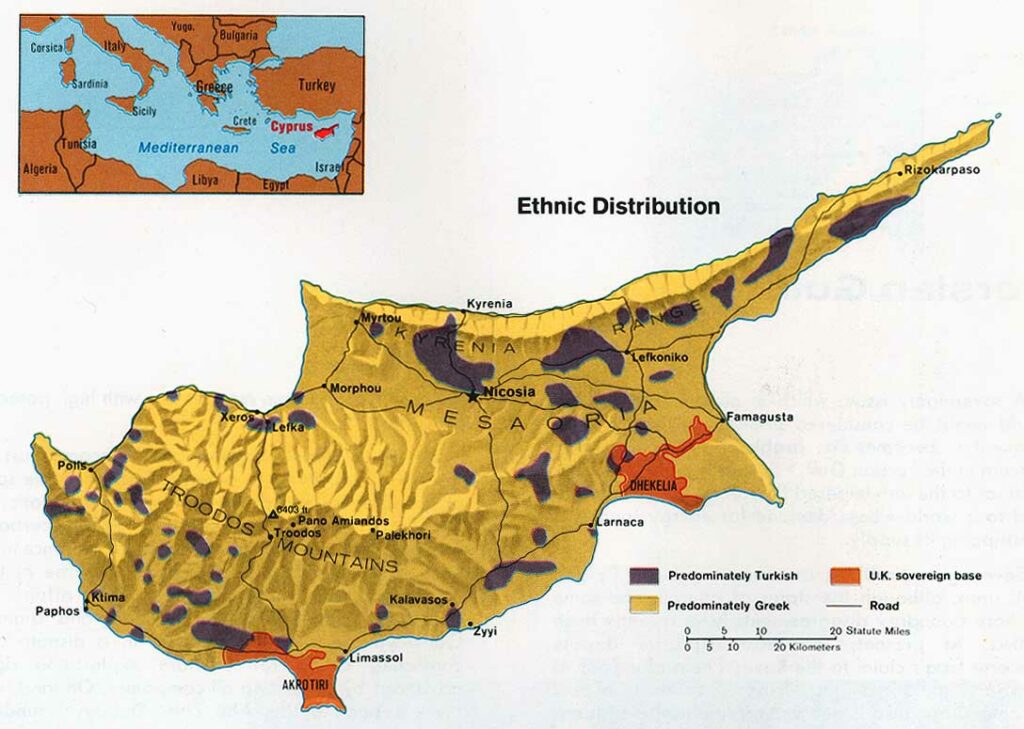

Today, Cyprus is essentially divided into three: there’s the Republic of Cyprus in the southern part of the island, making up roughly 60 percent of the island’s territory. The northern part, occupied by Turkey, makes up the other 40 percent, or thereabouts. In between the two is a UN-maintained buffer zone, which maintains the ceasefire between the two warring sides.

Though the north claims to be its own country, called the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, no country except Turkey recognizes it. Greek Cypriots and most of the world with them refer to it as either “the north” or as “the occupied territories,” an example we’ll follow.

It’s not just a two-way split, though: the United Kingdom, Cyprus’ erstwhile overlord, kept two slices of land for military bases after independence: Akrotiri near Limassol, and Dhekelia, between Larnaca and Famagusta. You can move between this territory and the Republic as you will, though, there’s no check or anything — though the bases themselves are obviously a little harder to get into.

Drawing Lines

The reason the UK is still in Cyprus is the easiest to explain: when the island gained independence in 1960, part of the deal was that Britain would keep some territory for itself for military ends. How that deal went down is a story of duplicity and shady diplomacy that is explained extremely well by William Mallinson in his A Modern History of Cyprus, a must-read for anybody interested in Cold War double dealings.

The line between Greek and Turkish Cypriots is a lot more complicated to explain. For hundreds of years, the two communities — Turkish Cypriots were roughly one-fifth of the population, with Greek Cypriots making up the other four-fifths, together with Arabs and Armenians — lived in relative peace together on the island: sure, there were issues, but nothing too serious.

Enosis vs Taksim

However, in the late 50s, Greek nationalism swept the island and an organization named EOKA — the Greek acronym for the National Organization of Cypriot Fighters — started a violent campaign against British rule. The aim was not independence, but rather enosis, unification with Greece.

Somewhat naturally, Turkish Cypriots didn’t really see a place for themselves in this nationalistic, Greek Cyprus — though it should be mentioned that EOKA at first made a point of not targeting Turkish Cypriots in any way. However, the ongoing campaign against the British and the associated outpouring of nationalist sentiments surely put the Mulsim minority ill at ease.

As a result, many Turkish Cypriots were in favor of continued British rule until a solution could be reached as to the fate of their community. Many Turkish Cypriots favored partition (taksim in Turkish) of the island into two parts. The smaller part for them, and the rest for the Greeks.

It should be noted that the British made good use of this split between the two communities, recruiting Turkish Cypriots into the police to help restore order in Cyprus’ cities and wage a guerilla war against EOKA in the countryside. Doing so definitely only further widened the rift between Turkish and Greek Cypriots.

Independence and After

The Turkish Cypriots didn’t remain in favor of British rule for long, though: they realized they were being played when British soldiers opened fire on Turkish Cypriots rioters. With continued pressure from EOKA and a litany of Turkish Cypriot organizations, the British eventually capitulated and decided to leave Cyprus.

However, to maintain some kind of peace on the island, Britain decided in negotiations with Greece and Turkey — you’ll note the Cypriots themselves weren’t invited — that the island would not be unified with Greece or partitioned. Instead it would gain independence, and the two communities would share power. In 1960 Cyprus attained independence after the Zürich and London Agreement.

However, in a fateful decision, Greece and Turkey would reserve the right to come to the aid of their respective communities on the island in case of trouble. Just 14 years later this decision would come to haunt all the players involved.

New Intercommunal Violence

The first few years of independence were relatively peaceful, but in 1963 things started going downhill again. The history here gets fuzzy, as both sides maintain a very different narrative of what exactly happened, but, in short, the government broke down.

The power sharing just didn’t work and the representatives of the two communities were at loggerheads almost constantly. The Greek Cypriots accused the Turkish Cypriots of sabotaging how the government worked and proposed that the constitution be changed so certain checks could be bypassed. This tactic, called the Akritas plan, led to the Turkish Cypriots walking out of government, never to return.

Around the same time, violence again erupted in several parts of the island, with armed militias of both sides exchanging fire and even killing unarmed civilians. In response, many Turkish Cypriots withdrew into so-called enclaves, dotted across the island.

Whether they withdrew out of fear of Greek Cypriot violence or because of pressure from their own community — pressure backed up by violent threats — remains a source of discussion and controversy. Our take is that it was a little of both: the Greek violence gave the Turkish Cypriot leadership an excuse to tighten their grip on their community.

Meanwhile, Greece and Turkey prepared for war both on the island as well as on their shared border in Thrace; it took the UK and the United States to prevent a war between the two NATO allies. To prevent further bloodshed on the island, a UN peacekeeping force, UNFICYP, was formed to maintain peace. There was no buffer zone, yet, though its foundation was laid.

Coup and Invasion

There was relative peace on the island until 1967, when a military junta took power in Athens during a bloody coup. The colonels wasted little time and immediately started pressuring the Cypriot president, Archbishop Makarios III, for unification with the motherland. Makarios, no fan of enosis, partially because he knew it would just lead to immense trouble with Turkey, resisted.

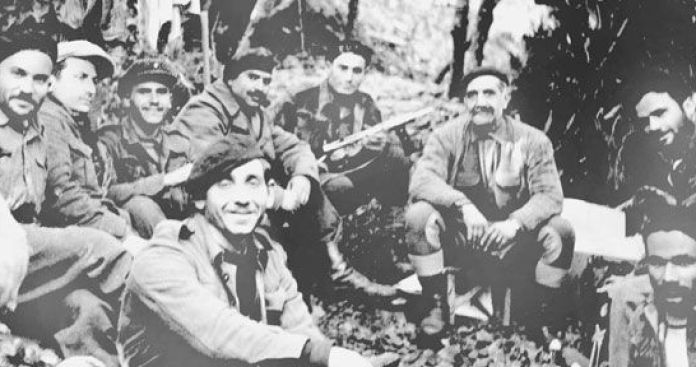

Thus started some nasty spy games, where the junta sponsored Greek fighters from EOKA to go to Cyprus and start a new organization, imaginatively named EOKA B, to overthrow the Cypriot government.

EOKA B skulked in the shadows for years, growing their own organization as well as recruiting members of the Cypriot National Guard and the Greek army into their scheme. In July 1974, they decided the time had come and seized power, deposing Makarios and declaring the Hellenic Republic of Cyprus, a puppet state whose sole aim was to be made part of Greece.

Understandably, chaos reigned as the coup progressed, with supporters of Makarios gunned down in the streets and Turkish Cypriots fleeing back into the enclaves. However, the new republic lasted only five days before the worst case scenario happened.

Turkish Invasion

In July 1974, Turkey made use of its right to intervene and invaded Cyprus. Initially, the Turkish army just set up a corridor between their bridgehead and the capital of Nicosia. Against expectation, Greece didn’t declare war in response because the junta collapsed on the news of the invasion and the newly installed democratic government had little appetite for war.

Peace talks between all the involved parties were quickly organized, but led to nothing, which made Turkey decide to invade again, only this time with overwhelming force.

This August invasion was a lot bigger, and pushed the defenders to the ceasefire line where it is today. The line held, but Turkey was also warned off by the UN not to go any further. The buffer zone was established, and thousands of refugees fled: Greek Cypriots fled south, while many Turkish Cypriots went north — though plenty decided to stay.

Aftermath

Roughly speaking, this is where we are today: though the north might think itself a country, it’s officially just occupied territory until Cyprus and Turkey can hammer out a deal, a deal that’s slow in coming despite several rounds of peace talks.

Currently, there is still a small Turkish Cypriot population living in the government-controlled areas, living their life in peace. In the north, meanwhile, extremely few Greek Cypriots remain, and a growing segment of the population is made up of settlers from the Turkish mainland — despite international law saying this is illegal.

As for the future, many Cypriots hope that one day the two communities can once again live in peace, like they used to — we’ve reported on one initiative here. Hopefully decades of hate can eventually be put aside, though the heaviest lifting will, as always, have to be done by politicians.

Articles you may also like

MUSEUM REVIEW – RAAF Amberley Aviation Heritage Centre

With the unfortunate cancellation of the 2022 Air Tattoo at RAAF Base Amberley, Qld, Team Aviation Report nonetheless made the pilgrimage from Melbourne to assess the works completed at the Aviation Heritage Centre since our last visit in the ‘teens. By Dion Makowski. It is clear a lot has occurred since our visit here a decade ago. […]

Walking with the Diggers

WALKING WITH THE DIGGERS The Centenary Commemoration of the Great War continues to unearth real treasures from our military history, none more mesmerising than this Exhibition of photographs taken by Australian Diggers, Sailors and Airmen in most theatres of the First World War. By Stephen Loosley This collection hasn’t been abroad for some 90 years. […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.