Before the glamorous flyers of the 1930s like Amelia Earhart, “Chubby” Miller and Nancy Bird Walton, another woman opened the way to the skies — and were it not for a tragic twist of fate, her name might now be just as familiar.

Her name was Millicent Maude Bryant, and in early 1927, she became the first woman to gain a pilot’s licence in Australia. She was also first in the Commonwealth outside Britain.

By James Vicars, University of New England.

A boundary-pusher who met an untimely end

Millicent was born in 1878 at Oberon and grew up near Trangi in western New South Wales. Her family, the Harveys, moved to Manly for a period after a younger brother, George, contracted polio (one of the treatments was “sea-bathing”). She met and married a public servant 15 years her senior, Edward Bryant. They had three children but the couple separated not long before Edward died in 1926.

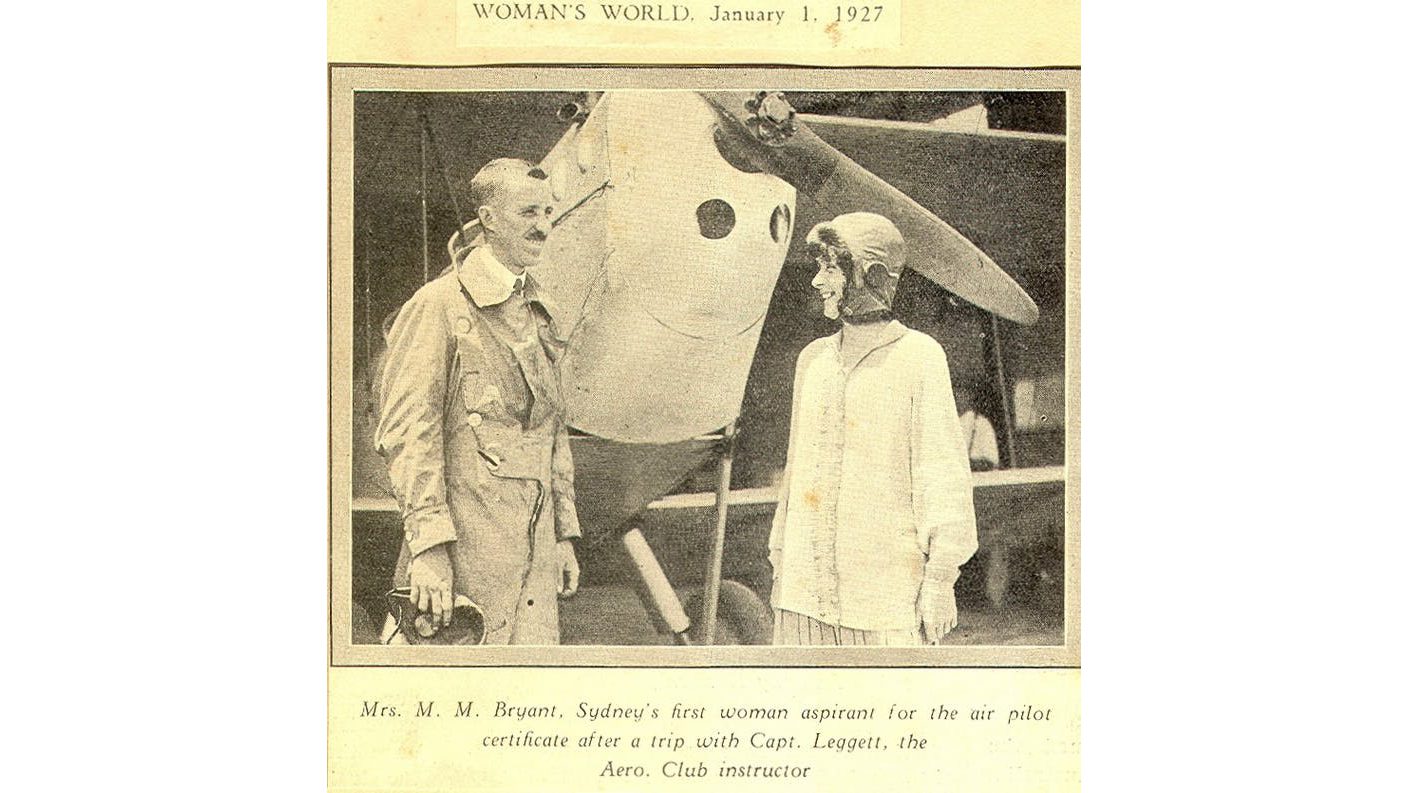

Later that year, Bryant began instruction with the Australian Aero Club at Mascot in Sydney. At the time, the site of the current international airport was just a large, grassy expanse with a few buildings and hangars.

Bryant was accepted by the Aero Club’s chief instructor, Captain Edward Leggatt (himself a noted first world war fighter pilot), soon after the club had opened its membership to women.

Even then, though, she was unusual: here was a 49-year-old mother of three taking up the challenge of flying which, in the 1920’s, was still as dangerous as it was exciting and glamorous.

Millicent Bryant (second from left) with other aviators beside her De Havilland Moth.

Author provided courtesy of Mary Taguchi.

She quickly progressed, ahead of two other younger, women students, and made her first solo flight in February, 1927. By this time, newspapers all around Australia were following her story, and in late March she took the test for the “A” licence that would enable her to independently fly De Havilland Moth biplanes.

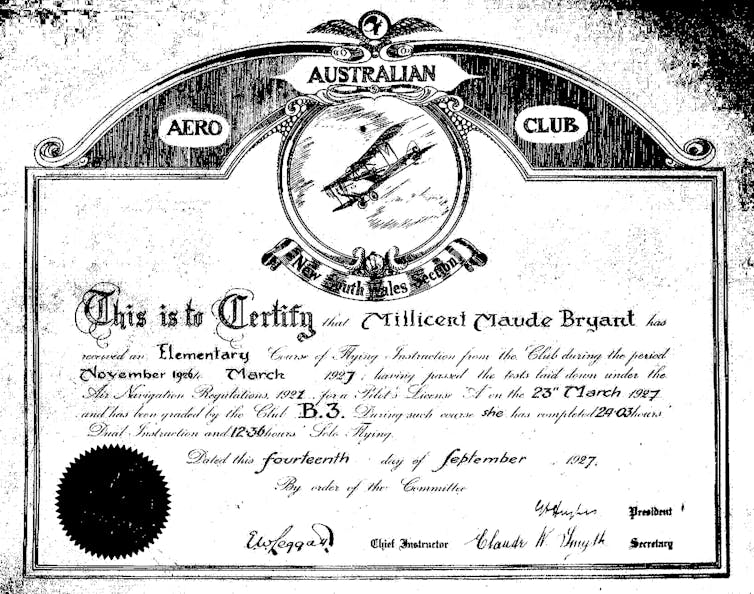

She passed, and with the issue of her licence by the Ministry of Defence, Bryant was acclaimed as the first woman to gain a pilot’s licence in Australia.

Millicent Bryant’s training certificate from the Aero Club of Australia (NSW Section). Her ‘A’ Licence was issued by the Department of Defence in April, 1927. Author provided.

Why, then, isn’t she better known in our day? While Bryant immediately began training for a licence to carry passengers and flew regularly in the months that followed, it was her particular misfortune to step onto the Sydney ferry Greycliffe on its regular 4.14pm run to Watson’s Bay on November 3, 1927.

Less than an hour later, she was among 40 dead after the ferry was cut in half off Bradley’s Head by the mail steamer Tahiti. It was Sydney’s worst peacetime maritime disaster. Bryant was still only 49.

Her funeral two days later was attended by hundreds of people and accorded a remarkable aerial tribute, as the Wellington Times reported:

Five aeroplanes from the Mascot aerodrome flew over the procession as it wended its way to the cemetery. As the burial service was read by the Rev. A. R. Ebbs, rector of St. Matthew’s, Manly, one of the planes descended to within about 150 feet of the grave, and there was dropped from it a wreath of red carnations and blue delphiniums … Attached to the floral tribute was a card bearing the following inscription:

5th November, 1927. With the deepest sympathy of the committee and members of the Australian Aero Club — N.S.W. section.

Lifting the wreck of the ferry, Greycliffe. The heavy lifting gear of the SHT steam sheerlegs is used to bring the hull section to the surface.

Author provided. Image from the Graeme Andrews ‘Working Harbour’ Collection, courtesy of the City of Sydney Archives. Author provided.

A pioneer in life as well as the sky

Bryant’s story quickly lapsed into obscurity. Fortunately, some 80 years later, the rediscovery in the family of a collection of letters and other writings has enabled Bryant’s life beyond her flying achievement to be rediscovered.

The letters were — and are still until they are added to the collection of Bryant’s papers in the National Library — held by her granddaughter, Millicent Jones of Kendall, NSW, who rediscovered them in storage at her home.

The main correspondence is a conversation with her second son, John, in England. It covers the period she was flying, though it only moderately expands on the flights recorded in her logbook.

However, her letters and writings reveal much more about Bryant herself, her relationships, her feelings and her leisure, business and political activities. And they make it apparent that she was as much a pioneer in life as well as in the sky.

For one, flying was not Bryant’s only unconventional interest. She was also an entrepreneur, registering an importing company in partnership with John, who went on to become a pioneer of the Australian dairy industry.

She opened a men’s clothing business, Chesterfield Men’s Mercery, in Sydney’s CBD. However, disaster struck when it was inundated with water mere weeks after opening, following a fire in the tea rooms upstairs.

Bryant then became a small-scale property developer, buying and building on land in Vaucluse and Edgecliffe. She’d been well tutored in this by her father, grazier Edmund Harvey (a grandfather of billionaire Gerry Harvey), whose own holdings eventually included a large part of the Kanimbla Valley west of the Blue Mountains.

An excellent horsewoman, Bryant was also an early motorist who had driven over 35,000 miles around NSW and who could fix her own car. She was a keen golfer and reader and even a student of Japanese at the University of Sydney.

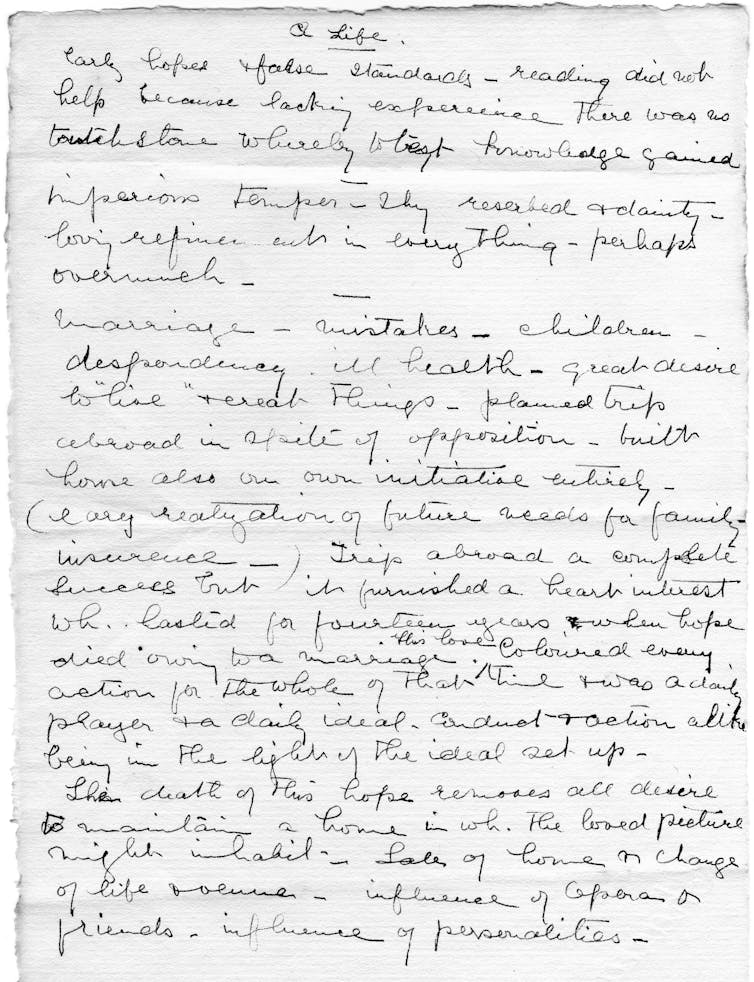

Several fragments of a family saga she planned to write, based on her own life, are among her papers. One sheet, entitled “A Life”, summarises in a series of rough notes rather more than she might have told anyone about her inner world.

Marriage – mistakes – children – despondency. Ill-health. Great desire to “live” and create things…

She notes that a trip abroad was a complete success but

it furnished a heart interest which lasted for fourteen years until hope died owing to a marriage.

This fragment provides some background to her taking, in her forties, the unusual step at that time of leaving her marriage and family home to start life afresh with her sons.

This was not long before she took her first flight, probably with Edgar Percival, a family friend and later a successful aircraft designer whose planes won air races and were noted for their graceful lines.

Vigour, values and conflicts

Growing up in the NSW inland late in the 19th century, Bryant would have begun with a fairly traditional view of what it meant to be a wife and mother.

However, her early life was also “free-spirited” (as one newspaper described her upbringing) and her determination to make decisions and shape her own life put her on a collision course with gender role expectations common at the time.

Learning to fly, especially in middle age, was a breakthrough she pursued perhaps even more keenly after being denied work with the Sydney Sun newspaper solely because she was married.

Bryant clearly came to hold strong ideas about what a woman could and couldn’t do, and her life shows a determination to make her own path, despite confronting obstacles that are still familiar in our own time.

Bryant is not just a figure in aviation history. Her life — spanning the colonial period, the newly-federated nation and the tragedies of World War I — came to reflect the vigour, values and conflicts of Australia in the early 20th century.

James Vicars, Sessional Lecturer, University of New England

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

A beautiful story of a remarkable, pioneering woman. Her untimely death leaves questions of what more she may have achieved…

Thank you History Guild.