Reading time: 9 minutes

On December 7, 2022, German federal police arrested 25 people who were allegedly plotting to violently overthrow the German government. This planned coup resurrected the spectre of a failed coup attempt 100 years before, when Adolf Hitler and his then still nascent Nazi party tried something similar. But is there a link between this modern coup and the one of 1923? Does the history of these events rhyme?

By Fergus O’Sullivan

To understand the links, insofar as there are any, we need to go over what happened in November 1923, as well as get an idea of the modern plotters’ plans. At first glance, the only thing the two events share is a hatred of liberal democracy, but perhaps more lurks beneath the surface.

The Beer Hall Putsch of 1923

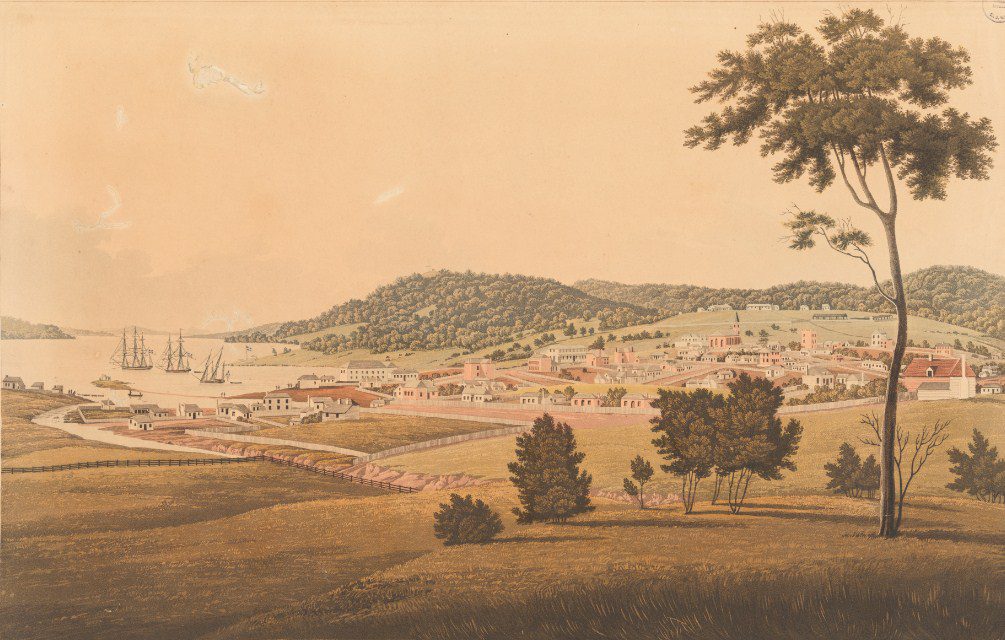

Germany in the early 1920s was a mess. After the First World War had ended in 1918, a new democratic republic was founded in the central German town of Weimar. However, the government of the so-called Weimar Republic would go down in history as one of the most ineffective ones in history. It came to an end when Adolf Hitler delivered the killing blow by becoming chancellor in 1933.

Not that Hitler and his Nazis — more formally known as the NSDAP, or national-socialist German workers’ party — hadn’t tried before. Ten years before his somewhat democratic accession to the highest office in the land, Hitler had attempted to overthrow the German government by more violent means. Then again, the Germany of 1923 was a more violent and chaotic place to begin with.

Germany After Versailles

Germany in 1923 was an anarchic place, constantly teetering on the edge and ready to fall into complete chaos. There were several reasons for this, but as with most issues the root was economic.

The punitive terms laid out by the victorious allies at Versailles had made Germany a debtor nation. Forced to pay damages to the countries it had been at war with, Germany saw huge sums flow out of its treasury to foreign countries, while unable to actually make any real money of its own since the Allies had also stripped it of its industrial base.

Unsurprisingly, economic disaster followed, most notable in the form of hyperinflation, some of the worst the world has ever seen. At the peak of the crisis, the German currency lost value every hour and poverty was rampant; many people couldn’t afford food.

Where there’s economic chaos, there usually is political turmoil, too. Hamstrung economically by the Treaty of Versailles, the Weimar Republic also lacked political power. The result was that the parliament was a seething cauldron of resentment in which there were many tiny parties at each others’ throats, making it hard to create strong, unified governments with a clear mandate.

This led to the Weimar Republic being a somewhat lawless place. In most major cities — and plenty of minor ones — it wasn’t the government and the police that held sway, but rather paramilitary groups made up of former soldiers and just about anybody else angry at the status quo.

Leading up to the Coup

In the southern German state of Bavaria and its biggest city Munich, the largest of those groups was the Kampfbund, or fighting-league, an amalgam of the NSDAP, its paramilitary wing the SA (Sturmabteilung or storm division) as well as two other violent right-wing groups. The NSDAP was the political arm of the league and directed the other groups where and when to smash heads.

The main enemy for the Nazis were the varied communist and socialist groups that had formed their own fighting organizations, though the Nazis would often clash with other rightwingers and the police as well. In fact, the melee got so bad that the Bavarian prime minister decided in September 1923 to declare a state of emergency in Bavaria and put a man named Gustav Ritter von Kahr in charge to keep order.

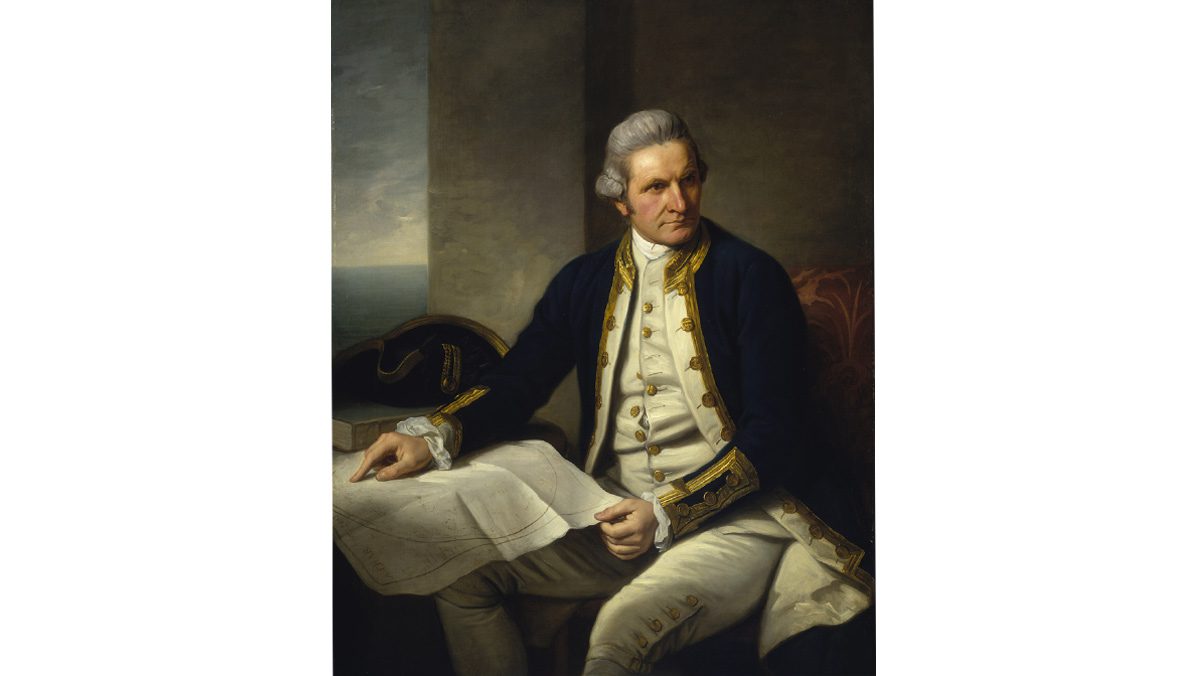

To protest martial law, Hitler decided to hold a series of meetings. Von Kahr immediately forbade these meetings, so Hitler decided to persuade von Kahr to come over to his side. To do so, Hitler brought the German war hero general Ludendorff into the fold. Ludendorff was held in high esteem by the veterans that made up the Kampfbund and with his support a real chance at power was realized.

Supposedly, the plan was to first take over Bavaria by deposing the government, and then march to Berlin and take over Germany as a whole. While this may sound a little crazy at first, it really can’t be overstated how unstable and weak the country was as a whole and how effective the SA’s brand of thuggery was in these circumstances. With a man like Ludendorff by his side, it wasn’t inconceivable that more would flock to the Nazis’ banner and strengthen their already not inconsiderable force of around 15,000 men.

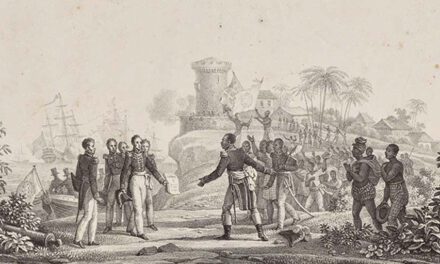

A Putsch in the Bürgerbräukeller

The coup, usually referred to by the German term Putsch, was started in the Bürgerbräukeller, a beer hall in central Munich on November 8, 1923. Though some later commentators used this location as a way to poke fun at the coup attempt — “look at these drunkards who wanted to overthrow the government” — beer halls like the Bürgerbräukeller were at the center of Bavarian civic life, then and now. It wasn’t that odd a place to kick off a grab for power.

At that moment, von Kahr, the man who ran Bavaria, was holding a speech for a few thousand of his supporters at the beer hall. Hitler marched in with the SA, had a machine gun set up, and declared that nobody would leave until von Kahr would join his effort to take over Bavaria.

Hitler hustled von Kahr and a few of his leading supporters into a room on the side and forced them accept cabinet positions in his new government. Von Kahr pretended to mull things over, but Hitler beat him to the punch and ran out into the hall, declaring von Kahr’s support. This show of enthusiasm energized some in the audience, and members of the SA streamed out, attempting to take over parts of the city.

However, an odd thing happened: in a certain way, nobody had been prepared for this kind of success, so quickly the putschists ran out of steam simply by virtue of not knowing what to do next. When the SA, spurred on by Ludendorff, stormed a local barracks of the regular army and were, unsurprisingly, fired upon, killing two SA men, the whole effort fell apart like a house of cards.

Von Kahr was able to take back control, Hitler and Ludendorff fled but were quickly arrested and Hitler was sentenced to prison where he wrote Mein Kampf (“my struggle”), the book that would launch his more legitimate political career and, eventually, his accession to chancellor in 1933.

The Reichsbürger Plot

From 1923, let’s go to 2022. Far from being a sick man hanging on by a thread, Germany is a powerhouse. The most populous and most industrialised nation in Europe, it leads the way within the EU in many ways, economically, politically and even militarily. While you could imagine the Weimar Republic being a mess without any real effort of the imagination, it seems odd that anybody would want to violently change the way Germany exists now.

Yet they did. A motley crew calling themselves Reichsbürger (“imperial citizens”) led by an aristocrat-turned-real-estate-developer, members of the military, a former member of parliament and an assortment of other oddballs numbering about 50 in total planned to rouse the army to storm parliament and take control of the country. The goal was to install the aristocrat as the monarch of a new Germany — yes, really.

It sounds crazy, but then again so does storming an army barracks in preparation for a march from Munich to Berlin. However, there are some key differences. For one, Germany isn’t a lawless hellhole, no matter how much the extreme right-wing media the Reichsbürger were imbibing might like to claim so.

Though modern Germany does have its issues, none of them are so serious that a large chunk of the German population would welcome a strongman taking over, especially one that claimed his throne by force.

That said, the Reichsbürger’s aims are frightening stuff. They envisioned storming the German parliament with armed men, taking over the government by force and installing a regime that would likely celebrate its inauguration with a river of blood. They draw their power from a strong, fanatical base of over 20,000 men and women, all of them, like the Nazis in 1923, disillusioned with liberal democracy.

Where in the 1920s it was the devastation of war and the ensuing economic chaos that drove the Nazis to their acts, the Reichsbürger seem more driven by anger of Covid restrictions. For example, one of their earlier plots involved kidnapping the German minister for health. On top of that, many members of the group seem enamoured of extremist groups from the States, like QAnon – a bizarre conspiracy that claims that many leading members of the Democratic Party are child-trafficking cannibals.

One parallel between the two events is the way many commentators, both now and then, dismissed the perpetrators as fringe dwellers who could never succeed. This led to right wing parties in the Weimar government believing that they could increase their supporter base by co-opting and controlling the Nazis. This reached it’s culmination in 1933 when Franz von Papen, a German conservative politician, asked Hitler to form a legal coalition government. To say this did not go as they planned would be quite the understatement! Similarities can be seen in the present in the way some right wing politicians have supported conspiracy theorists in order to gain votes from their followers. The German experience of the previous century shows this to be a path that is fraught with danger.

However, as frightening as this is, it does set this planned coup apart from the one in 1923: not only were the modern plotters discovered a lot earlier, their motivations are a lot different once you get past the fact that both groups aren’t fans of democracy. The world is a very different place, and the things the Nazis and the Reichsbürger believe aren’t interchangeable. That said, we’re still hoping nobody in the Reichsbürger group writes their memoirs in prison…

Podcast Episodes about German Coup attempts

Articles you may also like

Weekly History Quiz No.235

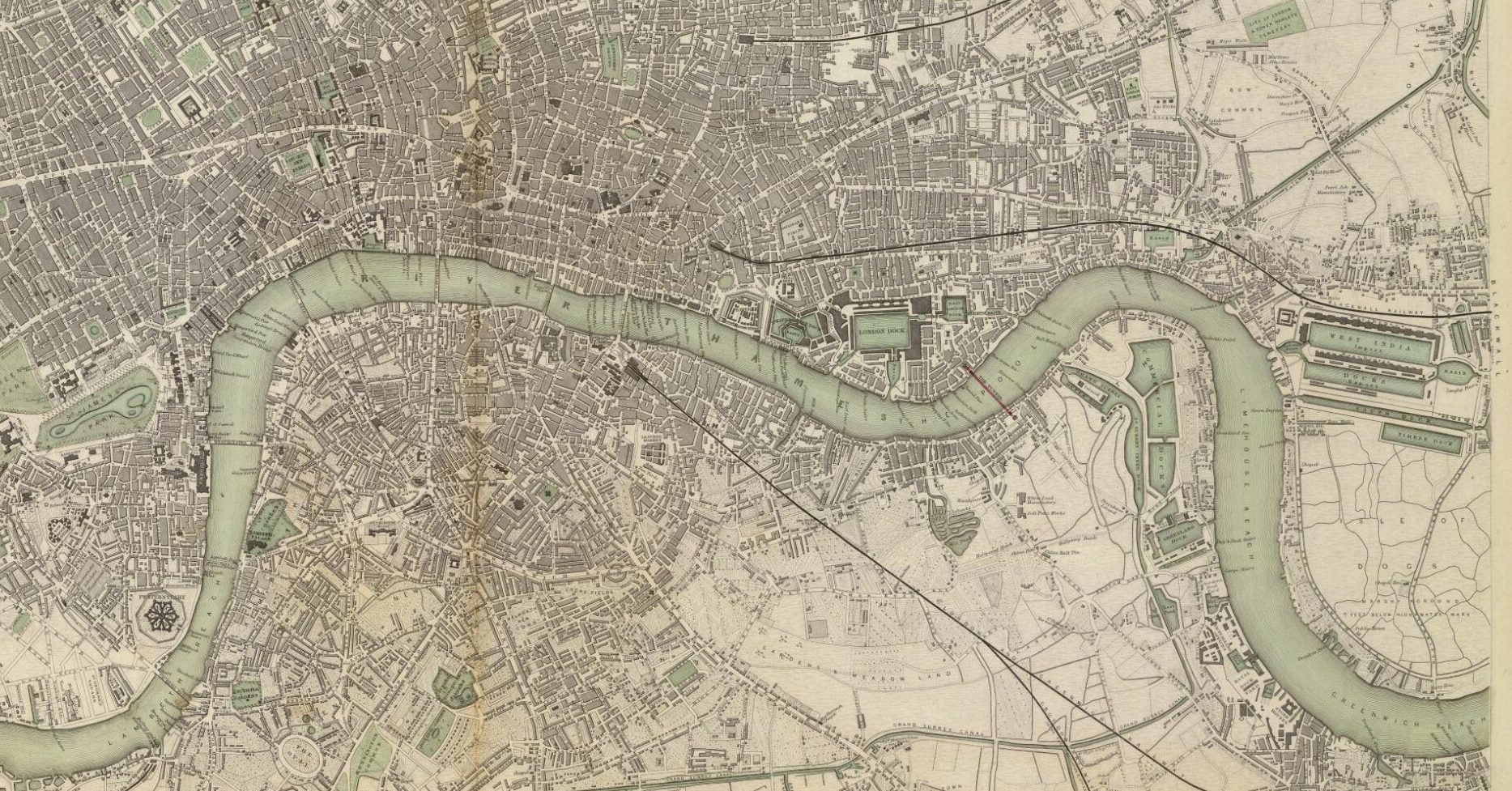

1. When did the construction of the London Underground begin?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

What is Environmental History?

Origins Environmental history is a rather new discipline that came into being during the 1960’s and 1970’s. It was a direct consequence of the growing awareness of worldwide environmental problems such as pollution of water and air by pesticides, depletion of the ozone layer and the enhanced greenhouse effect caused by human activity. In this development […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.