Reading time: 9 minutes

The best-known wartime innovations are the largest, loudest, and flashiest, from humble handguns to the tank. But war has also prompted the invention of fascinating, and less destructive, devices designed not to harm life, but to protect it. One of these was the anti-gravity suit, or g-suit.

By Morgan W. R. Dunn

The most visionary creation of a perceptive Sydney scientist, Frank Cotton, is little-known today. Noting the effects of acceleration on the human body, particularly the danger it posed of causing pilots to lose consciousness in demanding manoeuvres, he set out to invent a garment which would keep them alert and in the fight. While it would never enter service, Cotton’s g-suit was the first successful design of its kind, ushering in a new era of protective flight gear.

Frank Cotton’s Remarkable Career

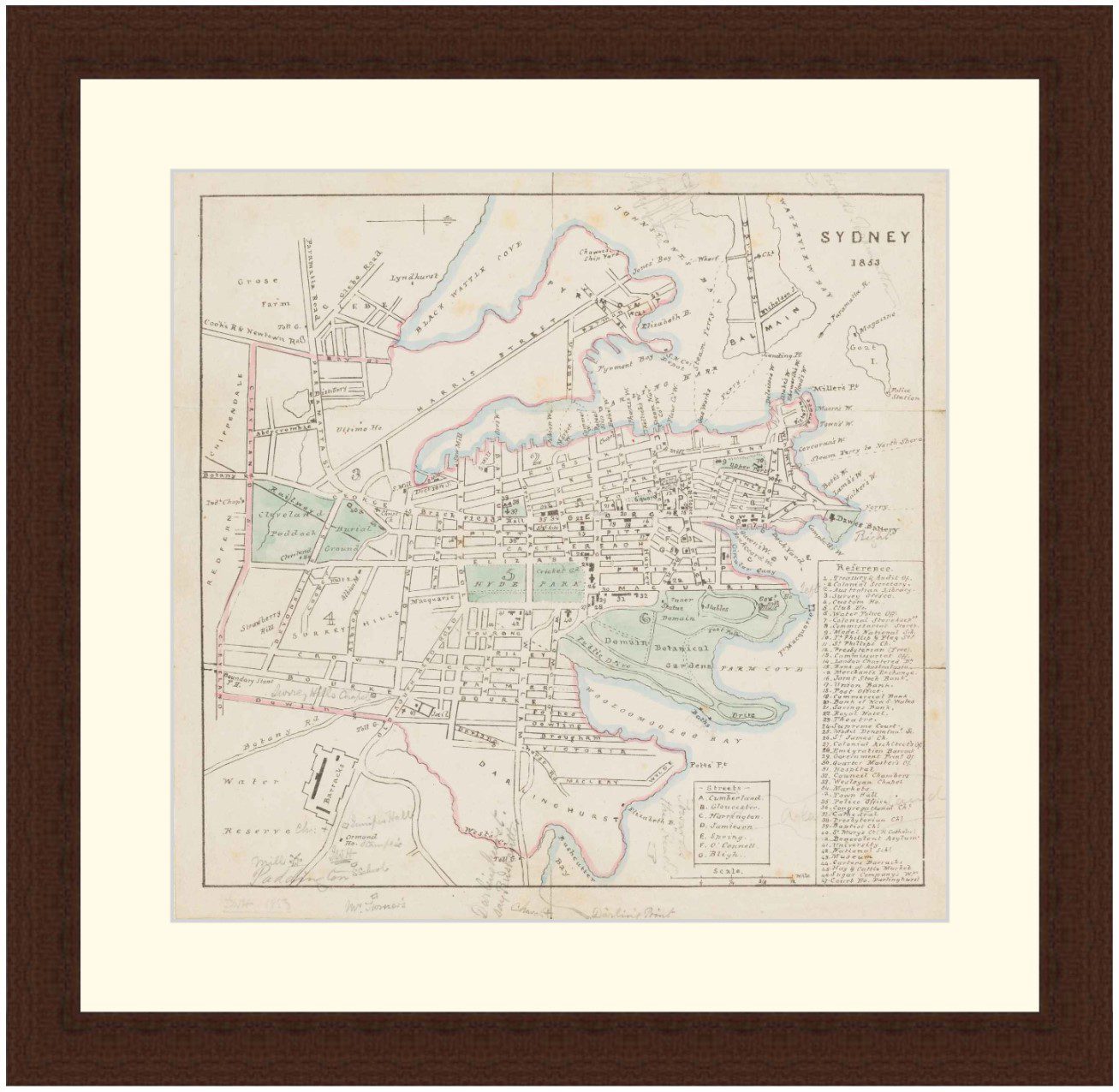

Frank Stanley Cotton, born in New South Wales in 1890, was fascinated by the effects of force on the human body from a young age. The son of Australian radical politician Francis Cotton, Frank’s early interest in sports led him to take his degree in physiology at the University of Sydney in 1912, specialising in the cardiovascular system. The following year, he became a lecturer and demonstrator in his field at the University.

A successful academic career followed, and by 1940 Cotton was a recognised expert in physiology. That same year, the Royal Air Force was fighting a relentless air war, the Battle of Britain, in which high-speed fighters had the critical role of chasing down and eliminating German bombers and attack aircraft. This meant using demanding aerial manoeuvres, which in turn meant pilots were regularly subjected to high g-forces.

One of Cotton’s notable achievements in his career was devising a method of determining the centre of gravity in a human body. While reading about the progressing Battle of Britain in September 1940, he realised he could use this knowledge to apply pressure to the body to maintain blood flow evenly, preventing pilots from passing out.

“Within days,” wrote historian Peter Hobbins of the University of Sydney, “Cotton was seeking support from the University of Sydney, the NH & MRC (National Health & Medical Research Council) and the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) to develop his invention: an inflatable anti-blackout suit.”

The Challenge of Gravity

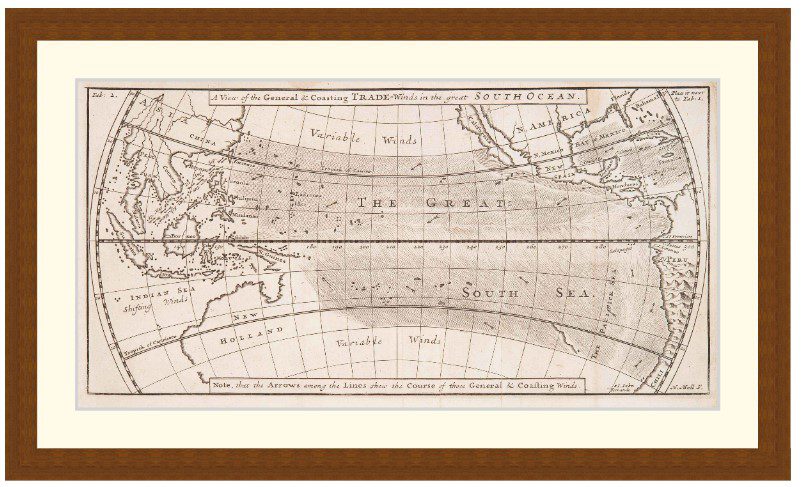

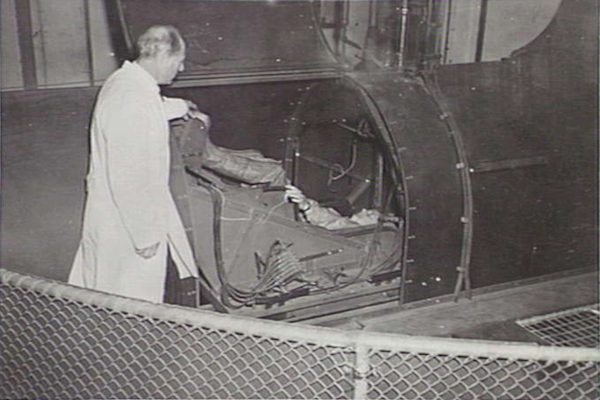

Cotton began working on designs for a rubber suit in several pieces covering the legs and abdomen. The Cotton Aerodynamic Anti-G (CAAG) suit, manufactured from latex-coated silk at the Dunlop Perdriau factory at Birkenhead Point, Sydney was the result of three years’ work.

When flying into a steep turn or pulling out of a dive, the force of acceleration, or g-force, is amplified, causing blood to drain away from the head and pool in the abdomen and legs and, if endured for too long, causing pilots to black out. This became a problem with the faster machines of the Second World War, during which pilots at risk of blacking out mid-flight were either limited in their tactics or at the mercy of enemy aircraft.

“A force of 5 ‘G’,” explains Hobbins, “can within seconds lead to a greying of vision, then a total loss of sight – ‘blackout’ – before producing unconsciousness. Pilots able to withstand high G for a few more seconds, or at a greater level, can potentially outmanoeuvre opponents to deadly effect.”

A body in flight can withstand up to 6g, or six times the weight of gravity, before blackout occurs as blood leaves the head. At higher gs, bladders in the CAAG inflated with carbon dioxide, keeping blood flow even. After extensive testing on a custom-built centrifuge, the CAAG was found to increase the average blackout threshold to 9g for five seconds, thus giving RAAF pilots significantly greater endurance and flexibility in aerial combat.

Cotton had solved, at least partially, the challenge of gravity. But getting his suits to where they could help the Allies win was a far greater problem.

Why the CAAG Wouldn’t Fly

Cotton’s g-suit would later be seen as “his most valuable contribution to the Allied war effort,” but the CAAG had remarkably few chances to make good on that value. The project suffered from numerous delays and further problems after it began to reach pilots.

One of several reasons for its three-year development time was that “the first prototypes created by Hardy Brothers failed miserably.” After switching to Dunlop Perdriau, Cotton found that Australian-made zippers, which ran down each leg of the suit to allow pilots to put them on quickly, were too fragile, while more durable North American zippers had to be obtained around rationing requirements and trans-Pacific shipping. Complicating matters was that each suit had to be custom-fitted for the wearer, leading to longer production times.

At last, after the suits saw early use with 452 Squadron, an RAAF Spitfire unit in Darwin in September 1943, they gained an early good reputation with pilots, who nicknamed them “zoot suits.” Imperial Japanese air units had been raiding Australian skies since February 1942. RAAF pilots saw that the CAAG could give them the edge they needed against Japanese opponents flying agile fighters.

But in November 1943, the Japanese air raids suddenly stopped. The pressure was mounting against the Empire: that same month, New Zealanders would seize Bougainville, and United States Marines would fight the Battle of Tarawa, the first of the savage island battles in the Central Pacific. Instead of harassing mainland Australia, Japanese air units were needed elsewhere for defence.

With no enemy over Australia to fight, pilots soured on the CAAG. At 10kg, the rubber suit was too heavy and hot for regular wear in tropical temperatures. Moreover, “the aircraft,” writes Hobbins, “was fitted not only with a carbon dioxide supply and regulator valve to inflate the suit, but also a combination of horns, buzzers and lights to warn pilots that they were either pulling more G than their aircraft could withstand, or turning so tightly that they risked an aerodynamic stall and falling from the sky.”

Pilots also worried the suit might increase the risk of drowning after bailing out. In the end, the CAAG was known to have played a part in downing a 452 Squadron Spitfire “because its pilot put on his CAAG suit incorrectly and it caught on the controls.”

A Useful Post-War Legacy

Cotton’s invention was a failure, but it was also a visionary device. Axis militaries never developed any equivalent, and the only major competitor to the CAAG was the water-padded g-suit developed by the Canadian medical researcher Wilbur R. Franks. Franks’ suits were equally hated by pilots, one claiming they felt “cold and clammy.” Complaints aside, however, pilots recognised the suits’ value. One wearer of the Franks suit, Seafire pilot Mike Crosley, recalled that during combat against FW190s and Me109s, “Thanks to my g-suit I remained conscious in the steep pull-out and regained altitude astern of their arse-end Charlie”

American engineers took an interest in the problem and saw the potential in both Franks’ and Cotton’s designs. After analysing samples of both, they eliminated enough flaws to produce the Spencer-Berger Single Pressure Suit G1, which satisfied the requirements of both raising g-tolerance while being comfortable and lightweight.

But this suit, while revolutionary, would only see limited use. Introduced too late in the war for full-scale production to begin, the G1’s successors, the G2, G3, and G3A would only be worn by a handful of Allied pilots before victory was achieved.

The discarded CAAG was rendered a relic, but it was an important development in high-altitude clothing. Eventually, lessons first learned in its design and construction, along with its Canadian and American counterparts, would inform the design of far more advanced suits in the jet age, and finally, pressure suits and spacesuits.

As for Cotton himself, he returned to his peaceable pre-war career, leading research in sports medicine through which he assisted the training of Olympians swimmers Denise Spencer, Judy-Joy Davies, and Jon Henricks, rower Peter Evatt, and sprinter Edwin Carr. Today remembered more as the “Father of Sport Science” in Australia, he nevertheless holds an important place in aerospace history.

Podcast episodes about the development of G Suits

Articles you may also like

Weekly History Quiz No.290

1. How many ships did the Battleship Bismarck sink?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

General History Quiz 198

1. What was the codename given to the 1940 Dunkirk evacuation?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

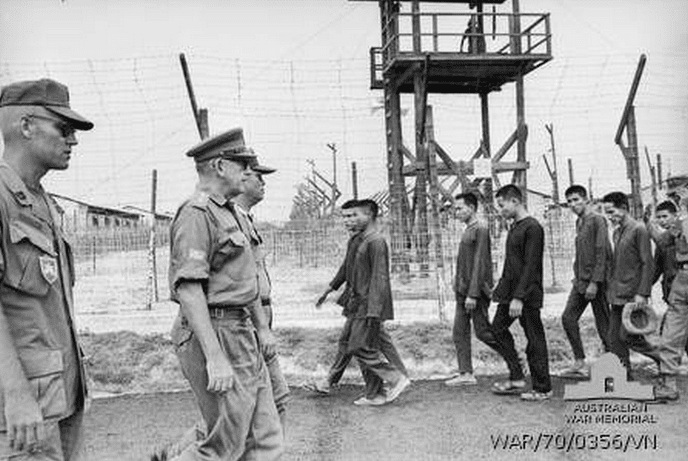

The changing lessons of Vietnam

Reading time: 5 minutes

The national effort at remembering should also revisit a series of 50-year anniversaries for Australia’s entry and enmeshment in the Vietnam War.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.