Reading time: 9 minutes

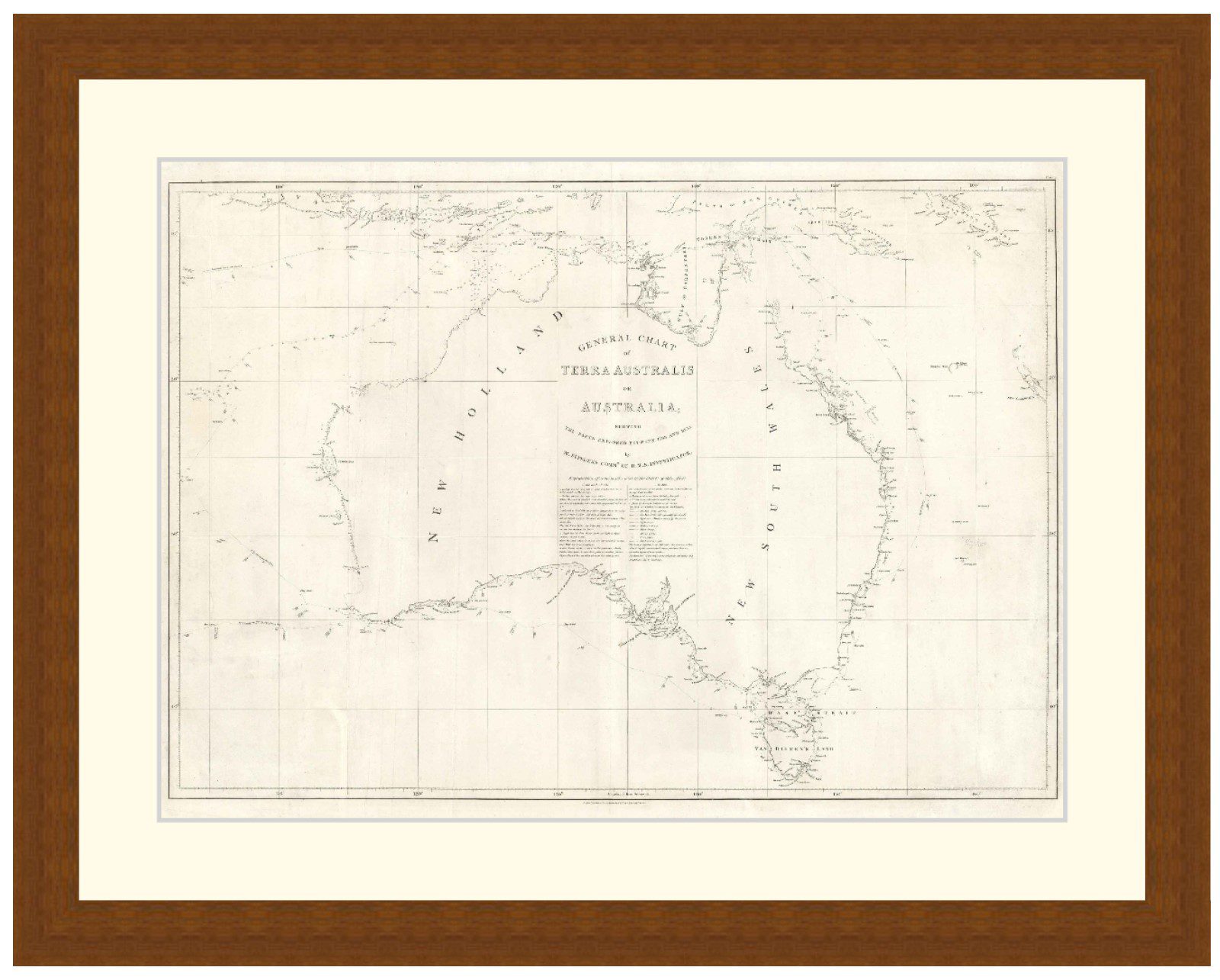

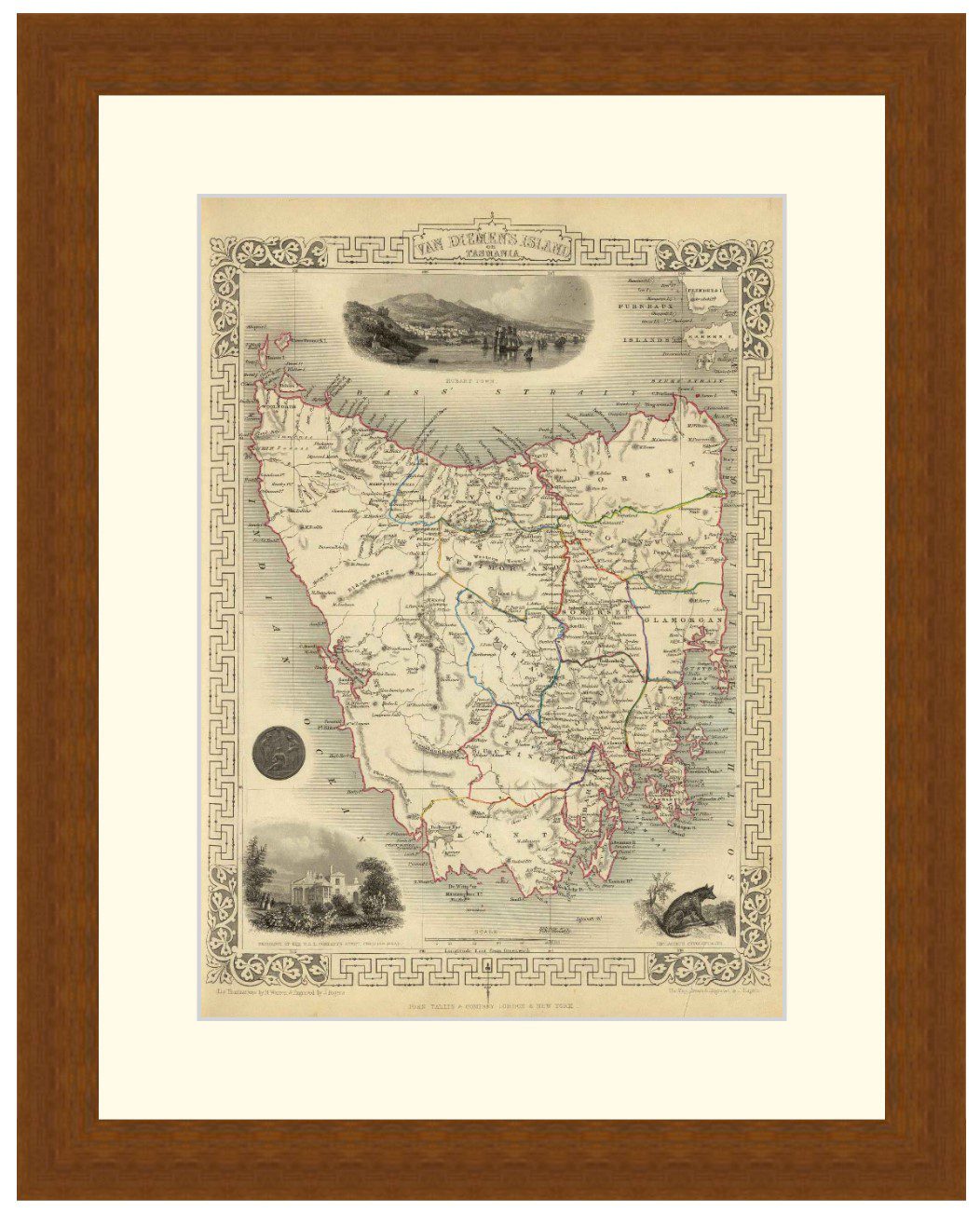

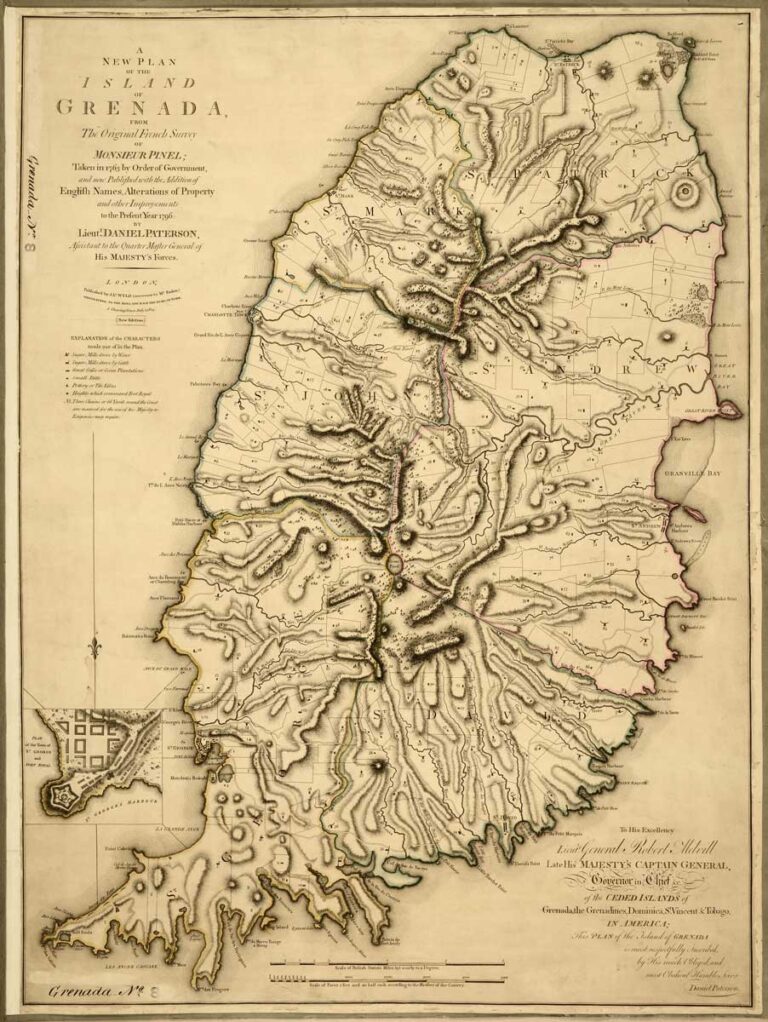

Late in the night of 2 March 1795, a rebellion broke out on the Caribbean island of Grenada. Grenada was a British colony, taken from the French in the mid-18th century. It still had a substantial francophone population. They had restricted political, religious and civil rights, particularly for those considered mixed race. The island also had a massive population of enslaved people ( around 30,000).

By Chris Day

Until May, the British government in London heard only rumours of the rebellion. Only then did the Home Secretary, the Duke of Portland (who was responsible for the colonies), receive a despatch from the island’s acting Governor, Kenneth Mackenzie, of ‘a General Insurrection of the French Free Coloured People’.

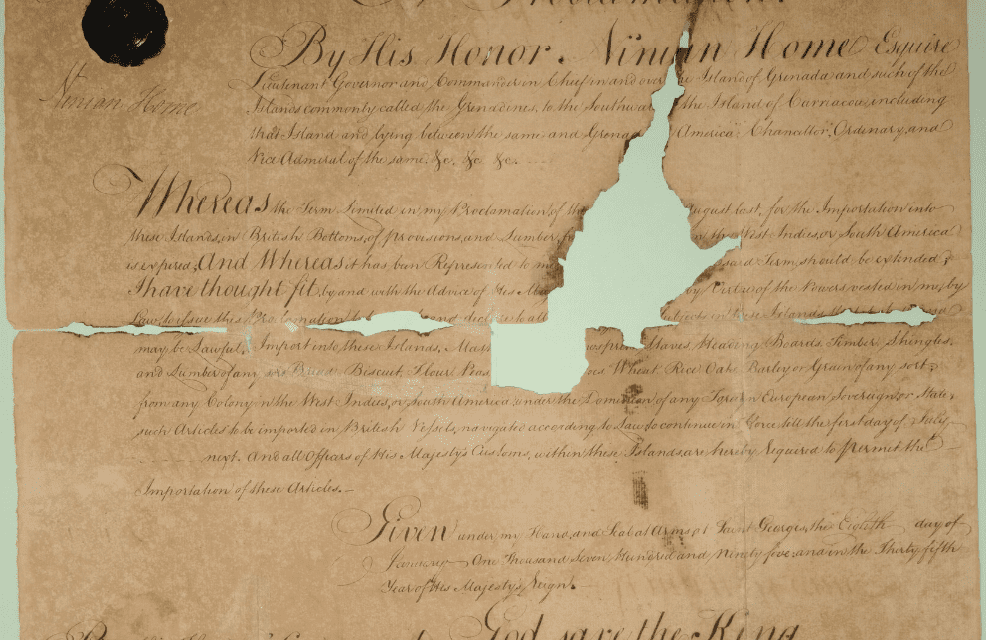

Led by Julien Fédon, the first action of the rebellion were two coordinated surprise attacks on the coastal settlements of Charlotte Town (also known as Gouyave), and Grenville Bay (La Baye). Grenville had been a scene of brutality, a ‘massacre of the English white Inhabitants’. Charlotte Town had been less characterised by bloodshed but had resulted in the capture of several of the white English population. Numbered among these was the former governor, Ninian Home, who had been away from St George’s, the Island’s capital 15 miles down the coast, to visit his estates (see footnote 1).

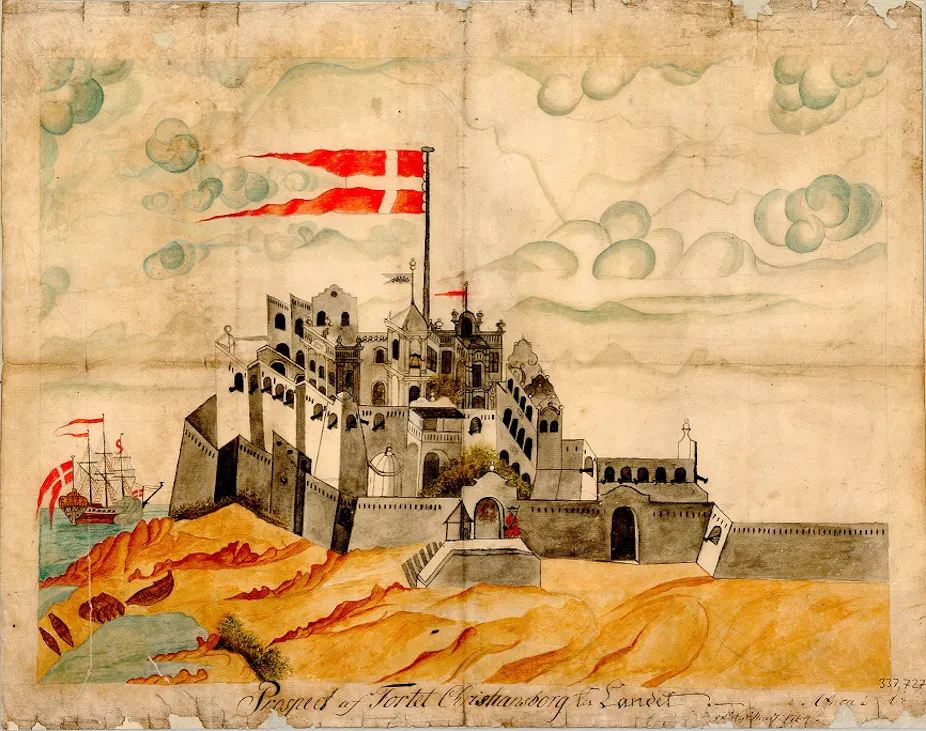

Support for the rebels

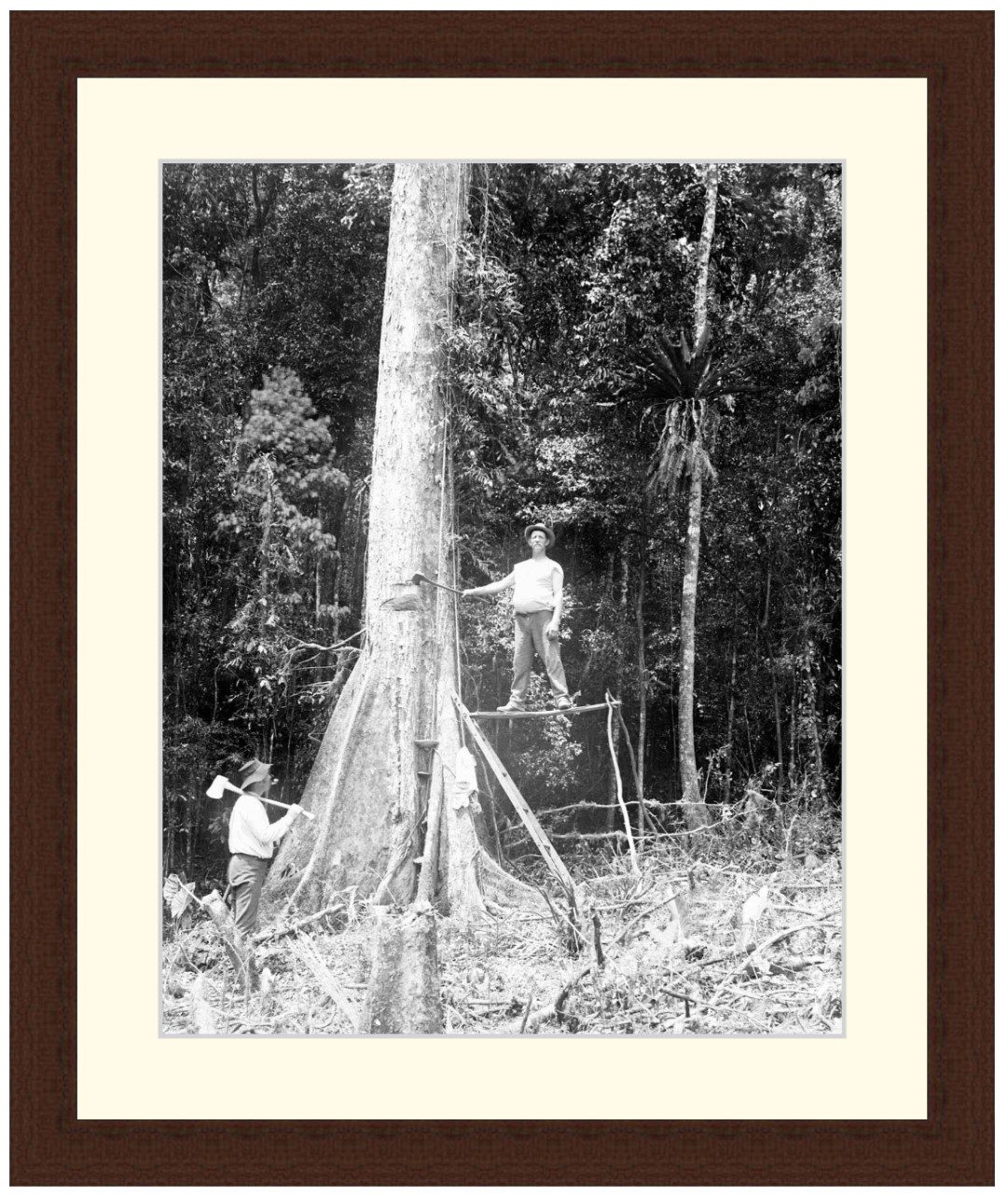

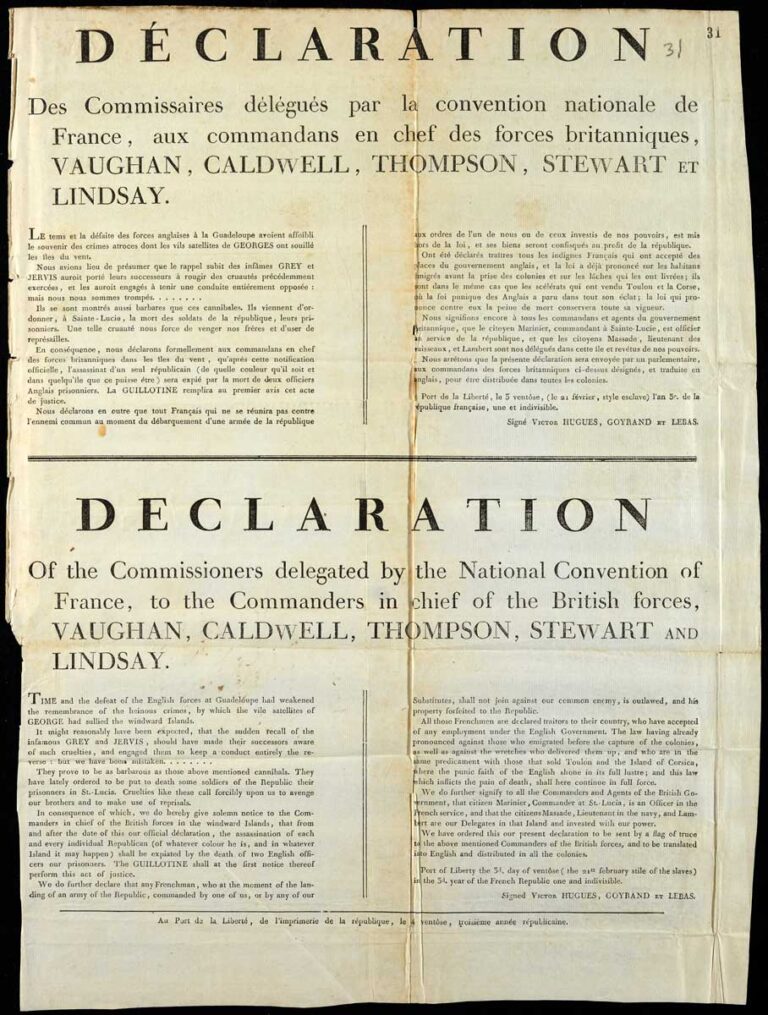

The rebels were backed by the French Republic. They had named Fédon as Grenada’s commandant general, and commissioned other rebels as French officers, providing them training and arms. Fédon had had his enslaved workers fortify his estate in the island’s mountainous and wooded interior, Belvidere.

The French were waging what they characterised as a war of liberation in the Caribbean. The Republic’s National Convention had decreed ‘absolute abolition of slavery’ and were attempting to foment rebellion across the British Caribbean. Fédon too said he would emancipate the enslaved, and some 7,000 joined his forces, one of the largest slave rebellions in the Caribbean (see footnote 2).

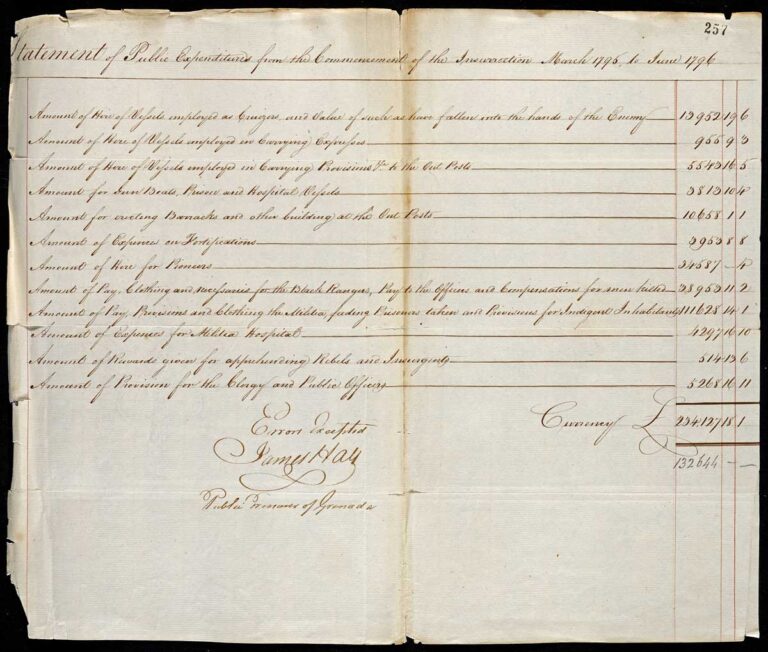

By May, when Mackenzie’s despatch arrived, the British forces were mostly confined to coastal towns. The rebels had the run of the interior, and were burning plantations with ferocity. London promised more troops, but they would not arrive until early 1796, after over a year of brutal, attritional warfare.

Treason as a weapon

Fédon and the other rebels were British subjects – they were committing treason. Like most British colonies, Grenada drew its authority and legal system from Britain, but made its own laws. In 1783, having taken the island back from the French, its Legislative Assembly had quickly empowered its courts to prosecute and decide in all ‘Criminal Matters … arising within this Island’ – including High Treason (see footnote 3).

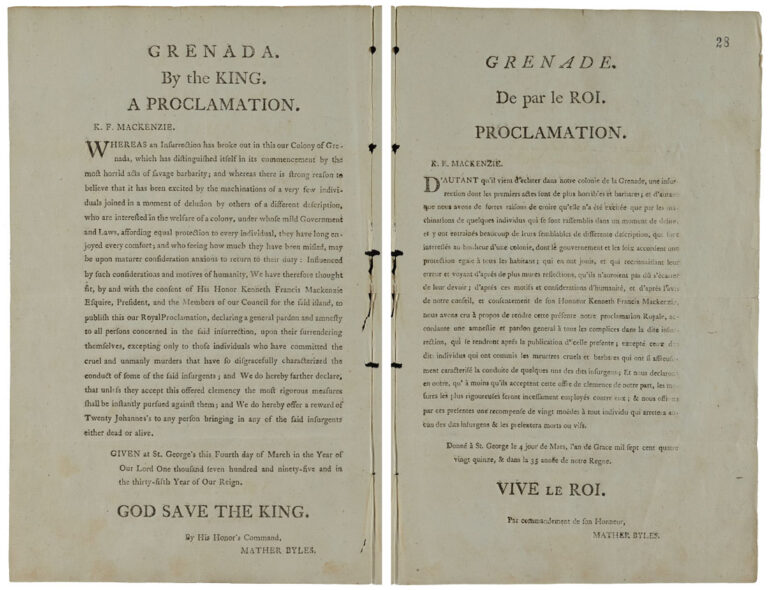

Treason is a talisman for states – its moral stain and brutal punishment stand as a symbol of the power of a government to destroy those who would oppose them. As the rebels looked to overwhelm them and they waited for reinforcements, the British colonists used it as a weapon of war. On 5 March 1795, two days after the rebellion had begun, acting Governor Mackenzie issued a proclamation offering an amnesty to those who had joined the rebels, promising to punish those who opposed to the full extent of the law. No rebels surrendered.

In consequence, in September 1795 the island’s Legislative Assembly had passed a Bill of Attainder, a legislative tool to render subjects traitors, more associated with Medieval and Tudor times than the late 18th century. It attainted some four-hundred-and-sixty-nine free rebels who had, ‘traitorously and in hostile manner taken up arms and levied War against His Most Gracious Majesty’.

The Bill of Attainder was, according to Samuel Mitchell (who took over from Mackenzie as Grenada’s next temporary Governor), ‘undoubtedly severe, but … absolutely necessary’. Mitchell stated his belief that the ‘tranquillity’ of Grenada would not be secure until the ‘entire deliverance from all French Connexion takes place’. In London, Portland’s advisers warned him of the attainder’s ‘excessive severity’ and dubious legality (see footnote 4).

Rebellion rising – and falling

For over a year the attainder was little more than a piece of paper, an attempt to project the power of the British Crown in a desperate situation on a distant island. The rebels had the upper hand.

After an attack on Belvidere, Ninian Home and other prisoners were executed. Plantations were devastated, and free people and enslaved people on both sides were massacred. Armed rebel canoes attacked British supply ships as they made their way to St. George’s. The rebels took ports, villages, and military outposts.

By 20 February 1796, the British had lost all of their outposts, and were confined to St George’s, unable to offensively meet the rebel army that looked likely to breach the capital’s defences.

In March, however, the promised troops arrived. By late March the rebels – themselves starving due to a breakdown of Fédon’s command, and the tendency of the liberated enslaved to destroy the plantations they had been brutalised on – had been forced back to Belvedere. By 4 July Grenada’s newly arrived Governor, Alexander Houstoun, informed Portland that, ‘The stronghold of the Insurgents, has been taken … [and] their principal body dispersed’. Many of the rebels had been killed or fled, and Houstoun was confident that the colony would soon be returned to ‘tranquillity’.

The rebellion’s bloodshed was replaced by that of the attainder. On 27 June 1796 a special court opened. Those named in the attainder were already confirmed traitors – the trials were merely to confirm who they were and to hear mitigation. Some 160 people were initially listed as accused. Many rebels had either died or fled (including Julien Fédon, who either escaped or died trying to). After three days, the first 48 men put before the court were declared to be traitors. All were sentenced to be executed the next morning (see footnote 5).

Outrage from different sides

In the colonies, the governor exercised the king’s royal prerogative of mercy. It was expected that in any case of multiple capital sentences, some would be respited – the ringleaders or worst offenders made examples of, others transported or imprisoned. Houstoun, disturbed by how little time he was given, chose fourteen ‘notorious’ rebels to die, respiting the rest for the time being.

The Grenadian slave owners who made up the court were outraged. They effectively threatened to go on strike if they were not allowed to condemn men ‘whose manifold crimes call loudly upon the Justice of the Country for speedy executions’.

But they were not alone in their outrage. When the Duke of Portland (and King George III) heard of what of transpired, he was enraged that, when the rebellion was no longer a threat, such a ‘Spirit of Revenge could have possessed itself of British Minds’ that the colonists would attempt to subvert the king’s ‘most precious and darling’ prerogative.

By the time Portland’s despatch reached Grenada, the court – having made their point – was sitting again. The executions continued, despite weak pleas for moderation from London, into 1797. At least 77 men suffered a death sentence. In October 1796 Houstoun had reported that almost all the executions were of mixed-race men, and a further 400 hundred were transported or banished. In the British Caribbean mercy, like everything else, was racialized (see footnote 6).

In the mid-nineteenth century, one Colonial Office official ruminated on the tiresome work of reviewing colonial legislation, characterising it as a series of ‘small struggles’ against badly drafted and often aggressively implemented laws.

By the late 18th century in Britain, Treason’s misuse was partially mitigated against by a robust legal system. But in the British Empire, it remained a blunt and brutal weapon (see footnote 7).

Footnotes

- The majority of quotes from Mackenzie, Portland and other colonial officials and politicians in this blog are drawn from The National Archives record CO 101/34: Colonial Office and predecessors: Grenada, Original Correspondence. Secretary of State, 21 November 1794 – 27 September 1796. This document has been catalogued to ‘item’ level, with each individual piece of correspondence (ie what was inside an envelope) given its own description.

- Journal des débats et des décrets, 17 Pluviôse an 2 [1794], p. 239. Available at: https://books.google.fr/books?id=UzpEAAAAcAAJ&hl=fr&pg=PA1#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed 13/07/2021). It is worth noting that the French’s declaration of the abolition of slavery was rarely translated into real emancipation for the enslaved peoples in its colonies. They often continued to be subjected to forced and brutalised labour, for instance in Saint Domingue (modern day Haiti). Napoleon formally reinstated slavery in French colonies in 1802.

- William Snagg (ed.), The Laws of Grenada, and the Grenadines; from the year 1766, to the year 1852: with a table of acts and a tabular and general index, (Thames Ditton, Surrey: Leonard Seeley, 1852), p.43

- Catalogue ref: CO 323/35, Law officers’ reports on Colonial Acts, 1791–1796

- British Library Endangered Archives Programme, Grenada: EAP295/2/6/1 Court of Oyer and Terminer for Trial of Attained Traitors record book [1796]. Available at: https://eap.bl.uk/archive-file/EAP295-2-6-1 (accessed 16/07/2021)

- TNA: CO 101/34, ff. 238-242; CO 101/35, ff. 5-7, 72-79; Timothy Ashby, ‘FÉDON’S REBELLION: Part Two’, p. 233; BL: EAP295/2/6/1. The author is grateful to the Endangered Archives Programme Team for providing him with a table of all the names in the attainder and the verdicts and sentences they suffered when known.

- Mandy Banton, ‘The Colonial Office, 1820-1955: Constantly the Subject of Small Struggles’, Masters, Servants and Magistrates in Britain and the Empire, 1562-1955, ed. Douglas Hay and Paul Craven, (London: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), pp. 251-302, pp. 251-252

This article was originally published in The National Archives.

Podcasts about the Grenadian Rebellion of 1795:

Articles you may also like:

This article was first published by The National Archives. It is reproduced in accordance with the Open Government Licence v3.0.