Reading time: 6 minutes

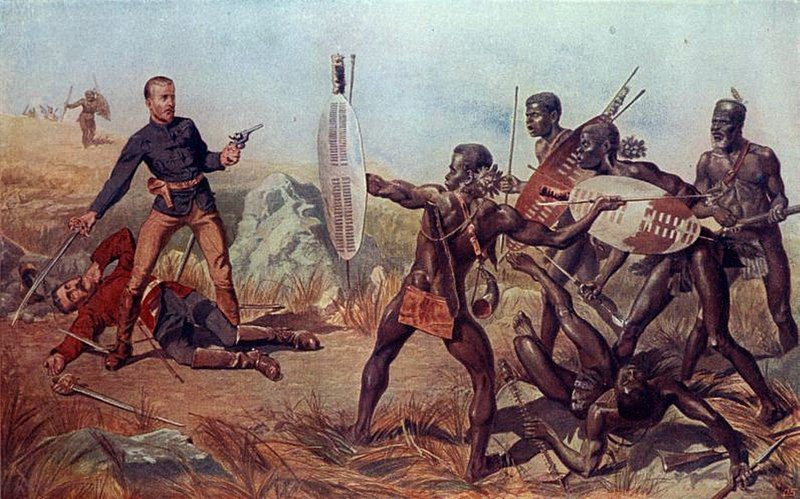

Many readers will be familiar with the 1964 epic movie Zulu, which depicts the 1879 landmark Battle of Rorke’s Drift in the Anglo-Zulu War. In the film, perhaps the most iconic scene takes place at the end of the movie, whereby the Zulu warriors chant in respectful salutation towards the British soldiers before withdrawing after the battle. Moving, cinematic, and honourable, it’s clear why the scene lives so memorably in the hearts of fans today.

By Madeleine Lily

However, what many unassuming moviegoers may not realise is that while the movie is, in many cases, embedded in fact, this iconic Zulu salute was actually the product of fictitious license. In other words, while Rorke’s Drift was a very real and notable engagement, the powerful Zulu salute seen on the screen did not actually happen.

Of course, it’s easy to brush off such as scene as yet another slightly rose-tinted adaptation of the truth, a way to move audiences through drama while still re-enacting the historic battle. However, it would be incorrect to state that such gallant acts of casting aside contention are purely just the stuff of cinema.

Although it may sound surprising, it is not unheard of throughout military history for enemy commanders to play active roles in the recognition and remembrance of their adversaries. In fact, three notable events during WWII come to mind, whereby direct nominations from German officers led to three allied servicemen receiving the most prestigious of British honors: the Victoria Cross.

Incidentally, while the Battle of Rorke’s Drift did not take place during WWII, it was following this engagement a remarkable eleven Victoria Crosses were awarded. So, despite the Zulu salute not occurring quite as viewers will see on the screen, it would be wrong to gloss over the immeasurable bravery displayed during this two-day conflict.

British Sergeant Thomas Frank Durrant was awarded his posthumous Victoria Cross following the events that took place in March 1942, off the docks of Saint Nazaire, France. During a seaborne raid, Durrant was manning a twin Lewis gun on a launch, which was faced with heavy fire while heading toward the port. Without cover, the sergeant was wounded, but this engagement was only the start of his spectacular display of perseverance.

The actions of the launch drew the attention of a much larger German destroyer, named the Jaguar, commanded by Kapitänleutnant F. K. Paul. Despite the injuries sustained by Durrant – including wounds to his head, arms, legs, and abdomen – and with the enemy searchlight upon him – the sergeant kept up the attack, with his gun and his grit keeping him propped up in determination.

The Jaguar called upon the launch to surrender but Durrant replied with even more fire. It was this display of unmatched, almost preposterous, bravery which led to Kapitänleutnant Paul visiting Durrant’s commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Newman, in a prisoner-of-war camp shortly after. To Newman, Paul shared details of the engagement, ultimately leading to a recommendation which earned Durrant the VC.

Sergeant Thomas Frank Durrant passed away from his injuries swiftly after being taken prisoner by the Jaguar, yet his ensuing Victoria Cross award – announced in 1945 – is visible to all at the Royal Engineers Museum in England today.

Traditionally awarded for valor “in the face of the enemy,” it’s typical to see recipients of the VC be recognized for continued, or even multiple acts of bravery. A significant example of such a case lies in another officer recommended for his posthumous VC by the Germans, Lieutenant Commander Gerard Broadmead Roope.

The captain of the WWII destroyer HMS Glowworm, Roope’s saga took place en route to Norway in April 1940. Alone in unforgiving weather and without backup, the Glowworm met two German destroyers and battle commenced. After the Glowworm had successfully damaged one of the destroyers, the pair withdrew into the gloom.

Now, although there was a possibility that the ships may be leading Glowworm into a trap, Roope’s pursued the battle. Sure enough, a mighty enemy cruiser loomed to meet them – the 14,000-ton Admiral Hipper. After sending a report to the Home Fleet to alert the side of the presence, Roope could have taken this opportunity to withdraw; however, in true Nelsonian Navy tradition, he went straight at ‘em.

Effectively facing off against three ships at once, it was unsurprising that the Glowworm sustained damage, with the vessel soon ending up in flames. Yet, Roope’s determination did not cease there. Severely damaged and aflame, Roope charged directly at the cruiser, firing torpedoes. As he turned away to ready the second salvo of torpedoes the Hipper closed the range with Glowworm. Seeing that he was running out of time Roope ordered the helmsman to ram Hipper. The collision broke off Glowworm’s bow and the rest of the ship scraped along Hipper’s side, gouging open several holes in the latter’s hull and destroying her forward starboard torpedo mounting.

Following this valour, Kapitän zur See Hellmuth Heye (the German captain of the Hipper,) penned a letter via the Red Cross, recommending Roope for the VC for his bravery. His recommendation was upheld, and Roope’s widow was presented with the award in 1946.

The final officer whose VC was awarded based upon evidence from the enemy is unique. The enemy were the only surviving witnesses to the bravery of his action. In 1943, New Zealand Flying Officer Lloyd Trigg spotted a surfaced U-boat from his Liberator V over the Atlantic. His bravery can be best described by his VC commendation.

Flying Officer Trigg had rendered outstanding service on convoy escort and antisubmarine duties. He had completed 46 operational sorties and had invariably displayed skill and courage of a very high order. One day in August 1943, Flying Officer Trigg undertook, as captain and pilot, a patrol in a Liberator although he had not previously made any operational sorties in that type of aircraft. After searching for 8 hours a surfaced U-boat was sighted. Flying Officer Trigg immediately prepared to attack. During the approach, the aircraft received many hits from the submarine’s anti-aircraft guns and burst into flames, which quickly enveloped the tail. The moment was critical. Flying Officer Trigg could have broken off the engagement and made a forced landing in the sea. But if he continued the attack, the aircraft would present a “no deflection” target to deadly accurate anti-aircraft fire, and every second spent in the air would increase the extent and intensity of the flames and diminish his chances of survival. There could have been no hesitation or doubt in his mind. He maintained his course in spite of the already precarious condition of his aircraft and executed a masterly attack. Skimming over the U-boat at less than 50 feet with anti-aircraft fire entering his opened bomb doors, Flying Officer Trigg dropped his bombs on and around the U-boat where they exploded with devastating effect. A short distance further on the Liberator dived into the sea with her gallant captain and crew. The U-boat sank within 20 minutes and some of her crew were picked up later in a rubber dinghy that had broken loose from the Liberator. The Battle of the Atlantic has yielded many fine stories of air attacks on underwater craft, but Flying Officer Trigg’s exploit stands out as an epic of grim determination and high courage. His was the path of duty that leads to glory.

Victoria Cross citation

The German U-boat’s survivors were able to commandeer the dinghy from the Liberator’s wreckage, and were rescued by the Royal Navy. Among these survivors was Oberleutnant Klemens Schamong, who reported the events to the British military, recommending Trigg receive an award for his incredible display of bravery. Just three months later, the Victoria Cross award was granted, and Trigg’s widow was presented with the medal just shy of what would have been his thirtieth birthday.

To be honoured in such a way – by one’s enemy – is remarkable, and almost raises the question of whether or not this unique recommendation almost adds further value to the already-prestigious honour. Would it mean more to receive recognition from one’s own side, or the enemy?

Podcasts about Bravery Commendations from the Enemy

Articles you may also like

The First World War continues: Britain’s dash for Mosul, Iraq, November 1918

Reading time: 7 minutes

After the armistice of 1918, why did the British occupy Mosul, Iraq? Dr John Slight looks at the continued hostilities in the Middle East after the guns fell silent on the Western Front.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.