Reading time: 6 minutes

Holiday in Hawaii and one of the birds you’re most likely to encounter is the chicken. You find them everywhere from beaches, to car parks and on walks through the bushland.

The locals warn that your chance of ever catching one are slim as these are wild birds, not the tame domestic kind found in farmyards and garden coops.

But chickens are not native to the Hawaiian islands, so how did they get there?

By Alan Cooper and Vicki Thomson.

Why did the chicken cross the Pacific?

They were brought as part of the early human migration across the Pacific, and we have used ancient chicken bones to try to gain new insights into this process, with the results published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA.

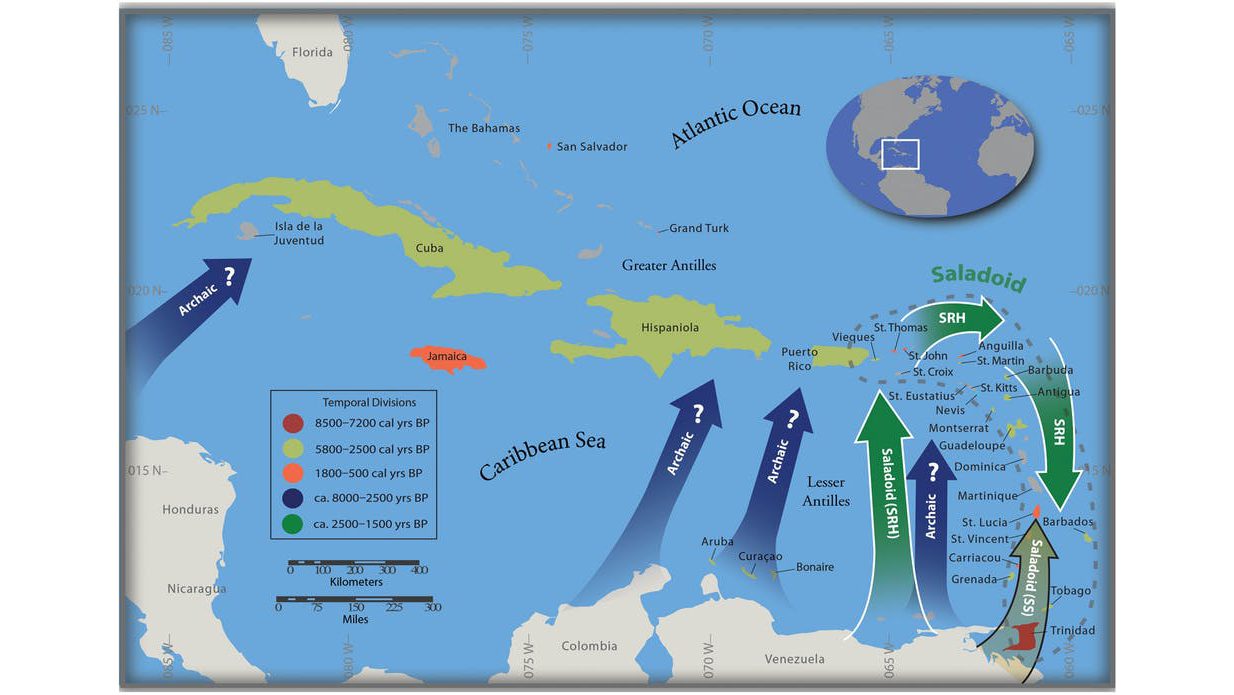

The colonisation of the remote Pacific was one of the great feats of human navigation. It started in Island Southeast Asia potentially in Taiwan, the Philippines, or Indonesia and moved across the vast expanse of ocean as far as Rapa Nui (Easter Island).

Although this is one of the most recent of major human migrations we still know relatively little about the routes or the processes involved. We also don’t know whether the eastward margin of this movement ended up contacting South America.

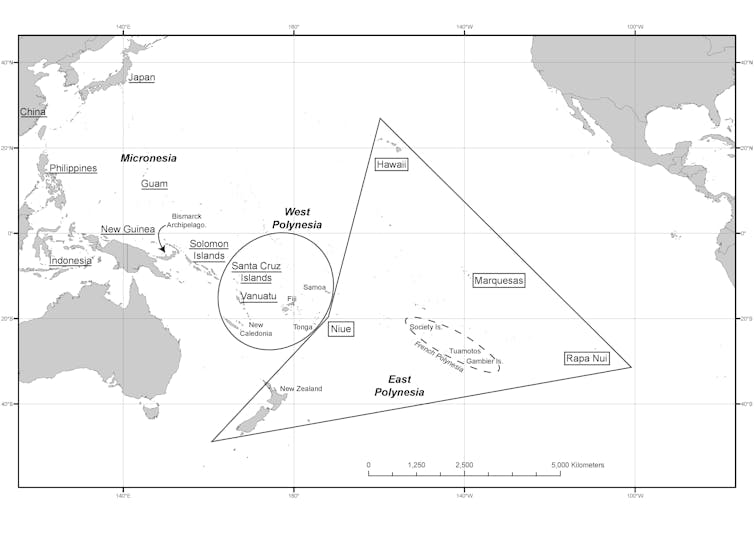

The first major oceanic human migration across the Pacific was the colonisation of western Polynesia (including Vanuatu, Fiji, Tonga, Samoa) around 3,250-3,100 years ago by the Lapita culture, who are generally thought to be the ancestors of the Micronesian and Polynesian cultures.

The Lapita culture was characterised by a distinctively decorated type of pottery, with the term “Lapita” originally based on archaeologist’s mishearing of the New Caledonian word “xapeta’a” – to dig a hole, or the place where one digs.

The colonisation of western Polynesia occurred only a few hundred years after the emergence of the distinctive pottery tradition in the Bismarck Archipelago, east of New Guinea, around 3,200 years ago, although its antecedents can be traced back to Island Southeast Asia.

The long pause

The initial movement into Western Polynesia was followed by a prolonged 1,800-year hiatus, or “pause” before further colonisation. This was perhaps related to the need to develop the navigational skills needed to cross the vast ocean barrier to the east (from Samoa to the Society Islands is 2,400km).

Following this, the remarkable navigational achievement of colonising the remote East Polynesian triangle, from Hawaii to Rapa Nui to New Zealand (an oceanic region roughly the size of North America) then occurred rapidly, in less than 300 years.

The huge expanse of empty ocean between these islands makes this a truly remarkable example of human technical ingenuity, and highlights the exploration capability of traditional pre-European cultures.

While human genetic signatures would provide the most accurate picture of these migrations, the population structures of many Pacific islands have been disrupted following European colonisation, and ancient skeletons are not common and have cultural taboos.

As a result, like in many other areas of the world, early human migrations have been tracked through the genetic signatures of the domestic animals and species such as pigs, rats and various plants they carried with them. These species are far more common in the archaeological record, and their study is free of many cultural restrictions.

The chicken run

We have used this approach to study the colonisation of the Pacific by sequencing DNA from ancient chicken bones recovered from archaeological sites, such as volcanic caves and beach middens, as well as from feathers of birds living on the islands today.

All of the ancient samples, and many of the modern birds, featured a characteristic Pacific genetic signature that is found nowhere else in the world apart from Island Southeast Asia. We have traced this lineage back at least as far as the Philippines, providing new clues about the origins of the Lapita peoples.

We also found that contamination with modern chicken DNA had misled a previous study that concluded there had been contact between Polynesians and pre-Columbian South America. That was based on similarities in ancient chicken DNA in each area.

We had already challenged these results because the genetic sequences involved were a common worldwide signature (which we informally call the “KFC sequence”) and provide no indication about past geographic connections. But when we re-analysed bones used in the earlier study we actually obtained entirely different results – only signs of the distinctive Pacific genetic signature.

The South America connection

Does this mean that there was no contact between Polynesians and pre-Columbian South America? All we can say is that the chicken sequences provide no support for the idea.

The presence of sweet potatoes in pre-European Polynesia has been seen as a strong indication of some form of contact. But plants and seeds can be also be dispersed by floating across large distances.

Recent work suggests this as the explanation for the African originated bottle gourd in South America, rather than the traditional view of human mediated dispersal.

Apart from marine dispersal by floating, it is also possible that Polynesians obtained the sweet potato through maritime trade, without coming into direct contact with the South American mainland. Early Spanish records detail the presence of large floating trading posts off the coast of Peru and Chile – think of the 1995 movie Waterworld without the annoying jetskis (two words joined at the hip).

So – what else do we now know? Well, one surprising result is that we found that chickens with the original Lapita/Polynesian genetic signatures are still present on many isolated Pacific islands such as the Solomon Islands, Marquesas and even more central spots such as Vanuatu.

This early domestic breed may contain valuable genetic diversity for modern poultry flocks which have become genetically impoverished during industrialised farming, and are at considerable risk from diseases such as avian influenza.

Who would have thought that the basket of birds at the bottom of an ocean-going canoe in the middle of the Pacific might one day end up on our plates?

This article was originally published on The Conversation.