Reading time: 13 minutes

A striking duality drove Australia’s thinking about France in the 20th century. Expressed as a chant it went: In Europe, Good! In the Pacific, Bad!

When Australia turns its gaze to Europe it sees France as an old ally, a cultural cornucopia and an expression of the Enlightenment. What finer destination could there be for an Oz traveller?

By Graeme Dobell, ASPI

In the South Pacific, though, Australia long saw France first as a colonial rival then, just a foe. The fear of France’s Napoleonic potential in the neighbourhood was one of the elements driving Australia to become a country in 1901. Australia found it a lot easier to love France when it was on the other side of the world. In the South Pacific, we oscillated between fear and forgetfulness.

The suspicion about what France is up to in the neighbourhood was present from the moment of settlement. Six days after Captain Arthur Phillip’s First Fleet reached Sydney in January, 1788, the French explorer Jean-François de Galaup La Perouse arrived. Contacts between the two parties were polite during La Perouse’s six week stay, but Phillip never met La Perouse and the British were secretive about their purposes and plans. Such cordial distrust flavoured much that followed.

Australia’s has a deeply-rooted strategic denial instinct in the South Pacific. The instinct drives a constant quest to be the top strategic partner for Island states while minimising the role of outside powers. The fact that Australia can never achieve complete strategic denial in the South Pacific means that the instinct is beset by a faint, constant ache. Throughout the 20th century, that ache was directed at France—with other targets such as Germany and the Soviet Union/Russia, going as well as coming.

Australia’s South Pacific fixations—and the strategic denial twinge—are founding elements of the Commonwealth, actually expressed in the Oz Constitution.

The Constitution makes no mention of the post of Prime Minister or the function of Cabinet government, but the South Pacific role gets an explicit tick. Section 51 is at the heart of the document, defining the legal powers of the Commonwealth over such areas as trade, currency, defence and communications. Subsection 29 identifies the power over External Affairs. The next clause, Subsection 30, goes further and identifies the power over the ‘relations of the Commonwealth with the islands of the Pacific.’ The two clauses express an implicit division of responsibilities. The new nation born in January, 1901, was happy to hand over the operation of most External Affairs powers to London; but, from the start, Australia would take hold of its interests in the South Pacific.

The Pacific element in the Constitution reflects the way the presence of other powers in the Pacific in the 19th century galvanised the six Australian states to federate.

The traditional inability of the states and the federal government to agree on much at all—still, today, a defining characteristic of the federation—makes the original act of creation even more striking. The first major convention of the states to discuss federation in 1883 was driven by the immediate need to get a common policy to oppose French and German colonisation in the Pacific. That was why New Zealand and Fiji were also at that first Sydney conference.

The first Australian spy, shortly after federation in 1901, was an Australian businessman who spoke French, dispatched to check French intentions in the Anglo–French condominium of the New Hebrides. France reciprocated the suspicion, and was still looking for Australian plots nearly 80 years later in the difficult breech birth that turned the New Hebrides condominium (aka: the pandemonium) into the independent nation of Vanuatu. The older residents of Noumea used to recall Australia’s naval show-of-force in World War 2, intended to ensure that New Caledonia sided with the Allies, rather than with Vichy France.

Australia’s dealings with France were strained by the traumatic birth of Vanuatu, Kanak unrest in New Caledonia in the 1980s, and 30 years of acrimony caused by French nuclear tests in Polynesia.

The twin issues of Kanak independence and French nuclear tests provided the then South Pacific Forum with high-profile, vital issues that united all Island leaders. France gave the Forum a convenient ‘hate figure’. The foreign foe is always a useful unifier.

One of the regional achievements of the Forum—the 1985 South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty—was made possible, and necessary, by anger at France. And France’s signing of the protocol of the Treaty, in 1996, enshrining the end to its nuclear tests, marked the moment when some rapprochement between Paris and the Pacific could truly begin.

The rapprochement process delivered France a big win last year—full membership of the Pacific Islands Forum for New Caledonia and French Polynesia. Forum membership is an early reward for the long-game France has played in New Caledonia over three decades. And next year that 30 year Accords process will be put to the vote in New Caledonia. The old Australian fear of France in the Pacific has faded.

The argument stretches over decades: can France stay in the South Pacific and, if so, on what terms? Being in the Pacific may serve the glory of France, but can France also act as a member of the Pacific?

When the war of words between Paris and Canberra was at its height in the 1980s, Australia’s Foreign Minister, Bill Hayden, crystallised a core proposition: Australia, he said, would be in the South Pacific forever, but you couldn’t necessarily say the same for France.

Hayden’s skepticism was grounded in a period when France seemed intent on ‘blowing up’ any hope of regional belonging—from nuclear tests to sabotage blasts in Auckland harbour. The France that went rogue and sank the Rainbow Warrior in 1985, killing photographer Fernando Pereira, has spent the following 30 years slowly adjusting its Pacific colours to try to become a different sort of regional warrior.

Grappling with that question of whether France can belong, Denise Fisher writes: ‘As in most key areas of France’s presence in the Pacific throughout history, ambiguity is rife’. That word ‘ambiguity’ keeps appearing. As Fisher notes, France’s behaviour is sometimes that of a power ‘in’ the Pacific, while at other times France can be a power ‘of’ the Pacific. New Caledonia’s vote next year will say much about whether France can be ‘of’ as well as ‘in’ the region. This is another three decade story.

After intermittent violence in New Caledonia through the 1980s, the moment of truth for the territory came in 1988. Members of the Kanak independence movement seized hostages on the island of Ouvea and demanded talks on independence. The fortnight siege from 22 April to 5 May—costing 25 lives—was broken by a military assault. To be a journalist in Noumea during this fraught period was to report on a society tearing at its own soul, peering into the abyss of civil war.

The Kanak leaders were urbanely French in language, manner and argument, but they wanted New Caledonia remade to serve Kanak identity, not French glory. Out of that tragic moment came the Matignon Agreements signed in June 1988, by the Kanak leader Jean-Marie Tjibaou, deferring the issue of independence for a decade. They were succeeded by the Noumea Accords with a 20 year timeline. For his leadership in stepping back from the brink, Tjibaou was assassinated the following year by a fellow Kanak.

The Matignon and Noumea Accords have allowed France to play a long game. Tjibaou, the independence leader, legitimised an autonomy process Paris could use to seek permanence, not departure.

Now, the moment for decision approaches. One parallel between 1988 and 2018 is that each date with destiny is framed by the French presidential election calendar. Next year’s vote is the moment of decision that eventually arrives for any peace process seeking to salve deep differences with lots of time and cash.

The New Caledonia Accords have influenced Australian thinking about other independence issues—as well as altering Canberra’s assessment of France’s capacity to stay in the region.

The Bougainville settlement brokered by New Zealand and carried through by Australia was an Anglo version of Matignon—the deferral of the immediate decision on independence as a means to stop conflict and embark on a long period of preparation and development.

Prime Minister John Howard invoked the Matignon model in his famous and notorious letter to Indonesia’s President B.J. Habibie on 19 December 1998, on the future of East Timor. Howard’s letter stressed Australia’s continuing support for Indonesia’s sovereignty in East Timor. Reflecting what Canberra thought France had achieved over the Matignon decade, Howard said Habibie’s offer of autonomy could become part of a lengthy process ‘to convince the East Timorese of the benefits of autonomy within the Indonesian Republic’.

The aim, Howard wrote, should be to avoid ‘an early and final decision of the future status of the province. One way of doing that would be to build into the autonomy package a review mechanism along the line of the Matignon Accords in New Caledonia. The Matignon Accords have enabled a compromise political solution to be implemented while deferring a referendum on the final status of New Caledonia for many years.’ The Howard letter illustrated Australia’s judgement that the Matignon/Noumea Accords delivered Kanak autonomy but could keep New Caledonia as part of France; Indonesia should take the same lengthy route to retain what it wanted.

Ten days before Howard wrote to Habibie, on 9 November 1998, Foreign Minister Alexander Downer, had warmly welcomed the New Caledonia referendum that strongly endorsed the Noumea Accord, stating:

‘A positive vote of over 70% and the high voter turnout demonstrate that New Caledonians want to assume greater responsibility for their own destiny. The result will maintain the impetus of political and social development in New Caledonia and help France to continue its constructive role in New Caledonia and the Pacific.’

Downer’s line about France maintaining its constructive role in the Pacific has become the new Canberra mantra. The South Pacific thinks France has rid itself of the habit of blowing things up. The Oz dread of France in the Pacific that ran through the 20th Century has faded. The dread has turn to desire…

Australia’s dread of France in the South Pacific in the 20th century has slowly turned into a new desire—that France stay and play and help pay.

As the quintessential status quo power in the South Pacific, Australia today embraces France as a new bastion of the existing, preferred order. The shift in Canberra’s thinking acknowledges how France has adapted its ways and adopted regionalist colours. No longer is France the feared as the outsider prone to blowing up—both bombs and its own interests.

Australia can embrace France as a fellow status quo power in the South Pacific because this is the region where the colonial powers stayed. Unlike Asia and Africa, decolonisation around here didn’t always equate to departure. Only Britain did a full exit—handing off to Australia and New Zealand as it left.

New Zealand set the decolonising-without-departing model by moving first, showing smarts and creativity. Wellington used a different model for each of its four colonies: Samoa became the first island state to get independence in 1962, with free movement to NZ for 20 years; Cook Islands got self government in 1965 (NZ sharing control of defence and foreign affairs); Niue got self government in free association with NZ in 1974 and Tokelau is a dependent territory of NZ.

Less deftly, but with equal determination, the US managed the same trick: America Samoa is an unincorporated territory, and America has compacts of free association with Marshall Islands, Micronesia and Palau (although it took eight referendums to get Palau’s compact ratified).

Compared to the Kiwis, France has taken nearly 50 years to decipher the decolonising-without-departure memo; perhaps the longest of long games was the only option, given the baggage Paris carried.

France has already scored a major win in the stay-and-play stakes: full membership of the Pacific Islands Forum. Even before New Caledonia votes next year, the South Pacific has rewarded France for its long game. The Forum last year announced the decision to admit New Caledonia and French Polynesia as full members (they’ve had associate membership since 2006). Two French controlled territories have joined the peak Island club that was created as an expression of Pacific independence.

Nic Maclellan rightly judges this ‘a momentous change’. The Forum which hammered out much of its identity and cohesion in fighting France, now accepts that ‘France seems to be in the Pacific to stay’. Theo Ell calls Forum membership the prize for ‘a marked change in French Pacific strategy, which was previously strongly individualistic and isolationist’. To normalise and reinforce its presence, Paul Soyez writes, France has embraced South Pacific regionalism, giving Noumea and Papeete enough autonomy to join in.

The Forum is the institutional expression of Australia and New Zealand as insiders, both ‘of’ and ‘in’ the South Pacific. For the Islands, the Forum is a mechanism to manage relations with Australia and New Zealand, as well as other big players outside the South Pacific. Equally, Australia and New Zealand use the Forum as a vehicle not just for regional consensus, but as a mechanism to create and police norms. The nature of the club reflects Island polities which are conservative, pro-Western, capitalist and Christian. That suits Australia wonderfully—as it will France.

France—through New Caledonia and French Polynesia—gets two seats at the top table for what will be a protracted argument about the nature of the Forum and the future of the Islands. More than a diplomatic debate, the wrangle goes to issues of power and identity, pitting Oz status quo interests against Fiji’s revisionism.

A key aim of Fiji revisionism is to strip Australia of its rights as an insider, to redefine regionalism so that Australia isn’t part of the South Pacific. In Fiji’s reimagining, Australia and New Zealand would be kicked out of the Forum. In that argument, Australia counts France a welcome reinforcement to the established order.

Proclaiming Australia’s ‘leadership role’ to deal with instability, natural disasters and climate change in the South Pacific, the 2016 Defence White Paper named a set of partners: New Zealand, France, the United States, and Japan. The hierarchy of lists always matters in White Papers and this is high rating for what France can deliver.

The White Paper’s discussion of France offered these three layers of history, international approach and new South Pacific partnership:

- Australia and France ‘share a longstanding and close defence relationship’;

- The two nations have a ‘shared commitment to addressing global security challenges such as terrorism and piracy’;

- And in the neighbourhood: ‘We are strong partners in the Pacific where France maintains important capabilities and we also work closely together to support the security in our respective Southern Ocean territories.’

The White Paper was published in February, 2016, and two months later France won the $50 billion submarine prize; the Oz–French strategic partnership shape-shifted to a new universe. In an ironic reversal of history, the South Pacific can now provide relationship ballast for the inevitable arguments and agonies of the sub build.

The long submarine marriage until 2050 will be marked by passionate, expensive acrimony between two disparate partners. And no divorce is possible in a huge project, as diabolically expensive as it’s technically difficult. In the decades ahead, partnership in the South Pacific may be the natural and easier part of the Oz–French relationship. Change, indeed.

This article was originally published in The Strategist.

Podcasts about Franco-Australian relations throughout history

Articles you may also like

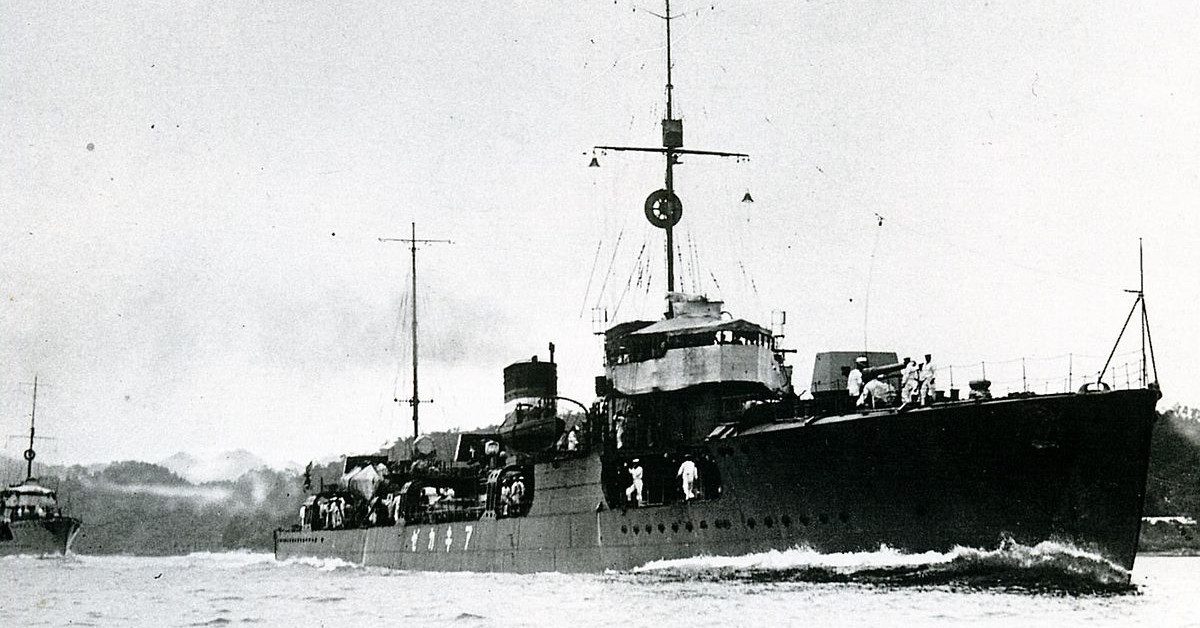

The Akikaze Massacre: the Japanese Navy’s Mass Murder in the Solomon Sea

Reading time: 12 minutes

When the Pacific War began in 1941, Japanese military planners had long recognised that they could not hope to win a protracted war against the United States, its likeliest and likely deadliest opponent in the Pacific. Instead, they pinned their hopes on a swift, devastating series of campaigns to seize strategic points.

How the Ancient Egyptian economy laid the groundwork for building the pyramids

Reading time: 5 minutes

In the shadow of the pyramids of Giza, lie the tombs of the courtiers and officials of the kings buried in the far greater structures. These men and women were the ones responsible for building the pyramids: the architects, military men, priests, and high-ranking state administrators. The latter were the ones who ran the country and were in charge of making sure that its finances were healthy enough to construct these monumental royal tombs that would, they hoped, outlast eternity.

The text of this article is republished from The Strategist under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License in accordance with their republishing policy.