Reading time: 10 minutes

On 18th July 1947, British rule in India came to an end, closing a 300-year old chapter in the history of the subcontinent. But another empire had been in India for over a century more, and it would be over a decade later that this longer story was finished.

By Morgan Dunn

That empire was Portugal, and since 1505 it had maintained a hold on a collection of tiny territorial concessions along the Indian coast. The largest of these tiny colonies was Goa. For years, calls for Portugal to hand over the territory went unheeded. Finally, India grew tired of waiting.

PORTUGAL IN INDIA

The Portuguese first came to Calicut in India in 1498, at the height of the European Age of Discovery. Whoever could establish ports and outposts in the far corners of the world could tap into rich veins of trade offering fabulous fortunes.

In 1510, an army under Afonso de Albuquerque captured Goa, almost 500 miles to the north of Calicut on India’s west coast. The Portuguese immediately relocated to the much more defensible city with its excellent harbor. Goa was eventually granted the same status as Lisbon in the Portuguese Empire, with its own legislature and a representative to the Portuguese monarch.

By 1947, Portugal’s Estado Novo, led by dictator António de Oliveira Salazar, had only just begun to develop Goa’s economy, drawing much of its wealth from selling Goan iron to Japan for its postwar reconstruction.

But independence rode on the edge of, and sustained, a wave of nationalist sentiment characterised by both satyagraha, or nonviolent resistance as practiced by Mohandas K. Gandhi, and outright belligerence. Mainland Indian and local Goan activists began to agitate against Portuguese rule with renewed energy after the Second World War came to a close.

In 1955, the same year France handed over control of their outpost in Pondicherry to the Indian government, thousands of non-violent protesters marched on Panaji, the Goan capital. Portuguese police responded by killing 22 and wounding over 200, feeding a growing nationwide wellspring of anger at the continued Portuguese presence

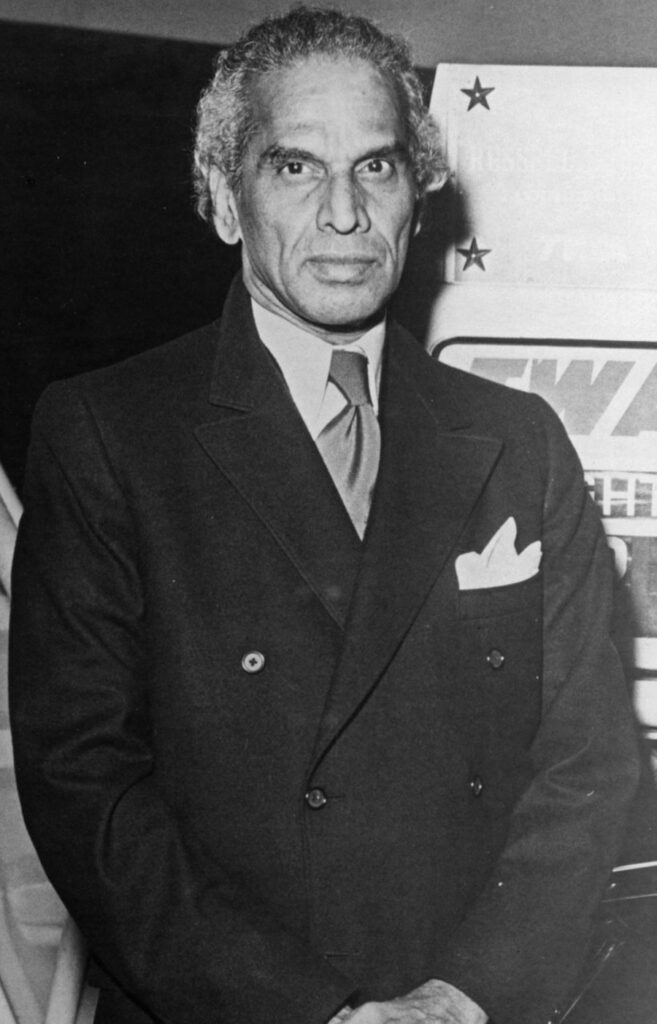

India’s Union government was slow to act on the Goan question at first. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru had come to power as a protege of Gandhi. Following independence, he’d overseen the use of Indian troops to violently annex the states of Hyderabad and Kashmir. But throughout the 1950s, Nehru was more interested in pursuing a non-violent foreign policy aligned with neither the United States nor the Soviet Union.

Portugal, on the other hand, was a charter member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, and as such an ally of the United States and the United Kingdom, both influential even after independence.

THE CONFLICT BEGINS

Nehru changed his approach as time progressed. On 27th February 1950, the Indian government made the first of many requests for a diplomatic solution to the Goa problem.

At home, Nehru’s public policy on the issue became increasingly hardened. “No power on earth can stop today the human tide of people in all dependent or semi-dependent countries from breaking all shackles of domination,” he told a crowd on India’s Independence Day in 1951.

The Salazar government refused, arguing that Goa was part of Portugal, and repeatedly ignored further requests until, in 1953, India severed diplomatic relations. India’s Defence Minister and United Nations representative, V. K. Krishna Menon, called the idea that Portuguese India was an integral part of its territory “a remarkable myth.”

The Nehru government imposed an economic blockade on the colony, choking its businesses and causing an economic disaster in Goa. At the same time, reports began to circulate in India that Portuguese police were torturing Goan independence activists.

Public demand for action swelled. While Nehru said that “the idea of using force was repugnant to Indian philosophy,” he also said that India “could not tolerate foreign military bases on her western coast.” India, he announced, “would not hesitate to take” “other steps” to rid the subcontinent of the last vestiges of European colonialism.

“Facing domestic flak over numerous developmental and security concerns, and faced for the first time with serious electoral challenges” in the late 1950s, Nehru defied international opposition and finally began preparations for a decisive end to the conflict.

The time was ripe. Portugal’s empire was beginning to crack at the seams: in Angola, pro-independence forces had begun to contest colonial rule in early 1961. It would take them 13 years to succeed..

“Goa,” said Nehru, “can be taken in three days.”

THE OPPOSING ARMIES

The decision to attack Goa was only finalised in November of 1961, but Indian military units had been preparing for the operation since that summer. The Indian Armed Forces were ready, having gained considerable experience in World War II, the invasions of Hyderabad and Kashmir, and the Korean War.

The Indian Army’s ranks were filled with hundreds of thousands of well-equipped soldiers. The Indian Air Force could deploy English Electric Canberra medium bombers and some of the most up-to-date fighters in the world, while the Indian Navy contributed a fleet of 16 ships led by the newly-acquired Majestic-class aircraft carrier INS Vikrant.

Defending the Portuguese outposts was a pitifully small force of a few thousand. Portuguese troop strengths had fluctuated in the city since Indian independence, sometimes rising as high as 12,000.

In 1961, the colony was manned by a small garrison of Europeans supported by native Goans and visiting contingents of Mozambicans and Angolans, both countries then under Portuguese rule, and armed police. Indian ground forces alone would outnumber the Portuguese by at least nine to one.

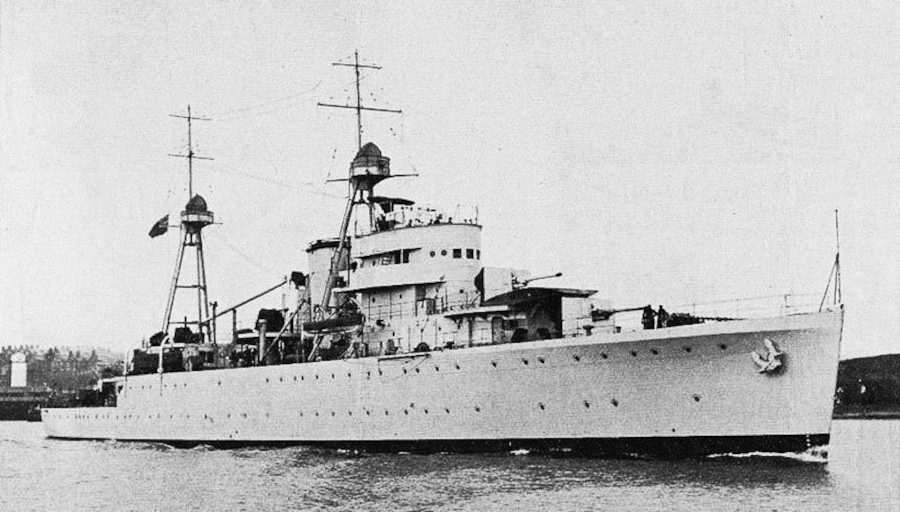

Portuguese naval forces consisted of a single sloop, the aging NRP Afonso de Albuquerque, and three patrol vessels, one in Goa, one in Daman, and one in Diu. The only air defenses were two civilian planes belonging to the Goan airline, TAIP, and several outdated anti-aircraft guns.

The Portuguese defenders were denied automatic and anti-tank weapons, portable radios, and armored vehicles or tanks; Lisbon wanted to avoid provoking Delhi. Astonishingly, despite the obvious hopelessness of the defenses, Salazar denied Governor-General Manuel António Vassalo e Silva the option of surrender.

As war loomed on December 14, 1961, he told the Governor-General “I do not foresee the possibility of a truce, nor Portuguese prisoners, as there will be no surrendered ships, because I feel that there can only be soldiers and sailors victorious or dead.”

Vassalo e Silva already faced an enemy he couldn’t beat. Now he couldn’t escape them.

THE TWO-DAY WAR

“Operation Vijay,” as Indian military planners dubbed it, began at midnight on the night of December 17. Two waves of IAF Canberra bombers swept over Goa’s Dabolim Airport, bombing the runway. Both planes on the apron later managed to escape carrying civilians.

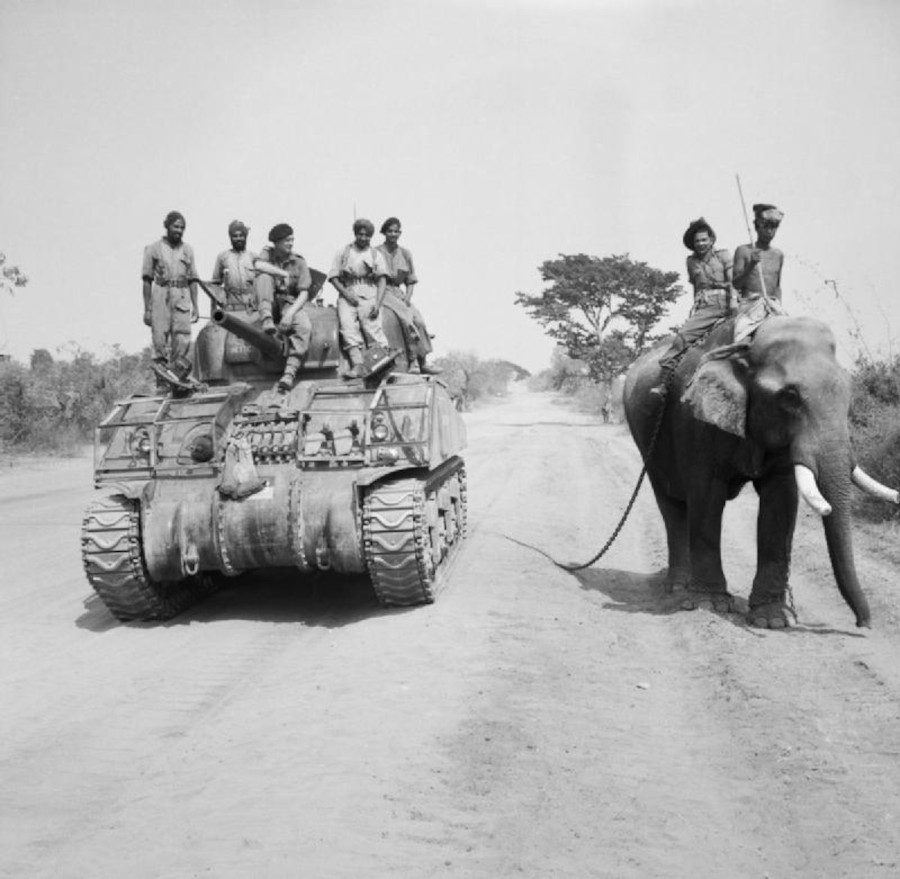

On the ground, the Indian Army’s 50th Parachute Brigade, supported by the 17th Infantry Division, attacked from the northeast. The 63rd and 48th Infantry Brigades attacked from the east. From the west came the 2nd Sikh Light Infantry and the 7th Light Cavalry, equipped with M4 Sherman tanks. None of them encountered much resistance as they raced to Panaji

The Portuguese defense was hampered by its lack of critical equipment as well as its strategy, the Plano Sentinela, or Sentinel Plan. The plan involved demolishing bridges and mining roads and buildings while Portuguese ground forces, divided into four groups, slowed the Indian advance.

Captain Carlos Azaredo, a cavalry officer stationed in Goa at the time, called the strategy “totally unrealistic and unachievable.”

India also took the advantage at sea. Three Indian Navy frigates bottled up the NRP Afonso de Albuquerque, anchored off the port city of Mormugão, and over the course of a four-hour battle, severely damaged the ship, killing several crewmembers and wounding its captain. The patrol boat assigned to Goa, the NRP Sirius, retreated and was scuttled.

Within 26 hours, Indian forces had captured the cities of Panaji, Mapuçá, and Bicholim, while Indian ships bombarded nearby Anjediva Island into submission. In the north, the Portuguese outposts at Daman and Diu surrendered after a few hours’ fighting.

Across all three territories, 22 Indian and 30 Portuguese soldiers had lost their lives. Casualties on both sides were “fewer than in road accidents over the Christmas week-end in Canada, as a Canadian newspaper put it.” Krishna Menon called the conflict “a swift and bloodless operation.”

With only 2,000 men left, Governor-General Vassalo e Silva gave in to the futility of his position and offered his surrender. Because he’d disobeyed orders, Vassalo e Silva was expelled from the Portuguese Army and shunned when he returned to Portugal. In 1975, he justified his decision in a book titled A Recusa do Sacrificio Inútil – or, The Refusal of Useless Sacrifice.

AFTERMATH

Jubilant Goans welcomed the Indian troops as liberators, while nearly 5,000 Portuguese soldiers were captured. Throughout the colonized world, India’s victory was celebrated, particularly in Portuguese Africa. Prominent voices in Britain, the United States, and Spain expressed outrage, while a Pakistani Foreign Ministry official called the attack “naked militarism.”

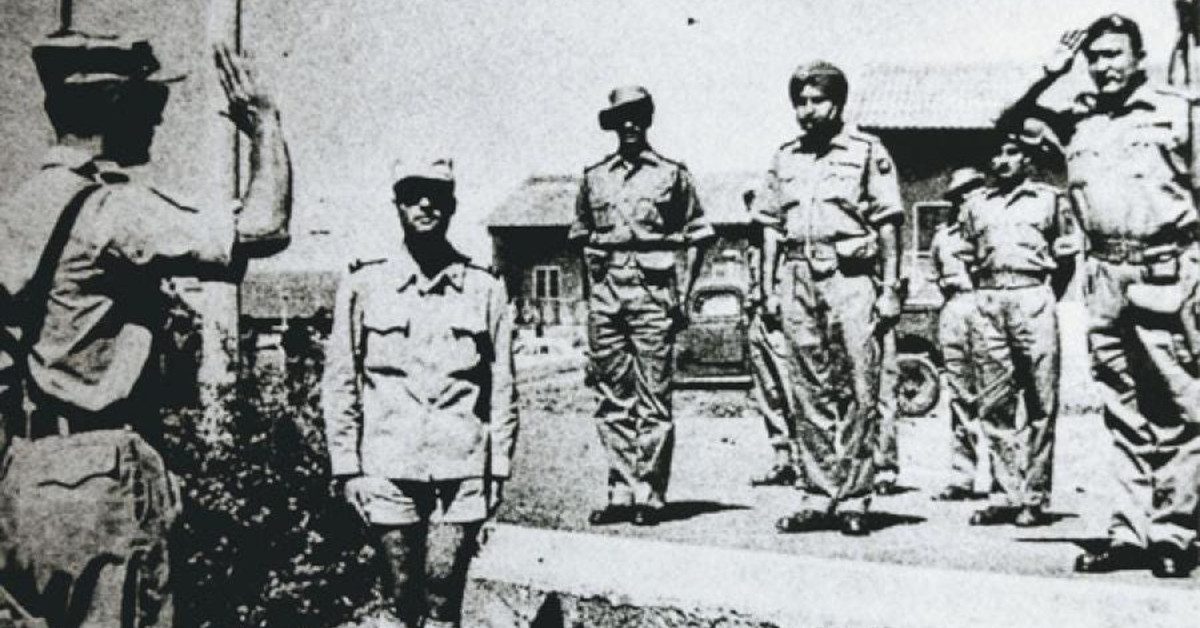

An Indian general, Kunhiraman Palat Candeth, was appointed military governor of the new union territory of Goa, Daman and Diu until early 1962, when a civilian government was formed.

For Portugal, the loss of Goa was only the beginning. A Portuguese writer at the time foretold that “Goa itself would be the starting point of Dr. Salazar’s decline!” The war begun in early 1961 in Angola would drag on until 1974.

That year, a group of young Portuguese army officers overthrew Salazar’s successor, Marcelo Caetano, in the nearly bloodless Carnation Revolution. A caretaker military junta granted independence to all of Portugal’s remaining colonies by 1975.

In the end, Nehru was wrong. Two days, not three, was all India needed to topple Portuguese rule in India, signalling the end of its timeworn overseas empire.

Podcasts about Portuguese Goa

Articles you may also like

The Chungking Legation: Australia’s first diplomatic mission to China, as soon to be wartime allies

Reading time: 6 minutes

Gough Whitlam’s visit to China in 1971 is an iconic moment in the history of Australia-China relations. As prime minister, he officially recognised the People’s Republic of China the following year, heralding a new era of engagement with China.

But Whitlam’s visit overshadows an earlier and equally significant moment in Australia’s relationship with China.

On October 28 1941, Australia opened its first diplomatic mission in China, a legation in the wartime capital of Chungking (Chongqing) in central Szechwan (Sichuan) province.

General History Quiz 144

1. The 430 BCE plague of Athens coincided with what event?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.