Reading time: 11 minutes

From the most ancient settlers, over 50,000 years ago, to battling empires in the 20th century, Goodenough Island has offered a vantage point over the Solomon Sea and an eastern gateway to the island of Papua.

By Morgan W. R. Dunn

A peacefully settled island for much of its history, Goodenough was also the site of one of Australia’s earliest daring successes in the struggle against the Empire of Japan.

The Ancient and Modern History of Goodenough Island

Goodenough Island, like the rest of the region of Melanesia, is home to one of the oldest stable human populations on Earth. The earliest Papuan settlers began hopping the islands of northern Oceania over 40,000 years ago, moving from northwest to southeast before arriving in what is now Milne Bay Province, with Nidula, or Goodenough Island, to the east, close to Moratau (Fergusson) and Duau (Normanby) Islands.

The first settlements on Goodenough Island, reflecting the oceangoing habits of their founders, were established on the coast, ringing Mount Vineuo, or Mount Oiautukekea, an 8,300-foot (2,500 metres) peak at the centre of the island. For over 30,000 years, the islanders were content with these homes, but the Austronesian migration displaced the older Papuans from 4,000 BCE, pushing many inland and onto the slopes of the mountain.

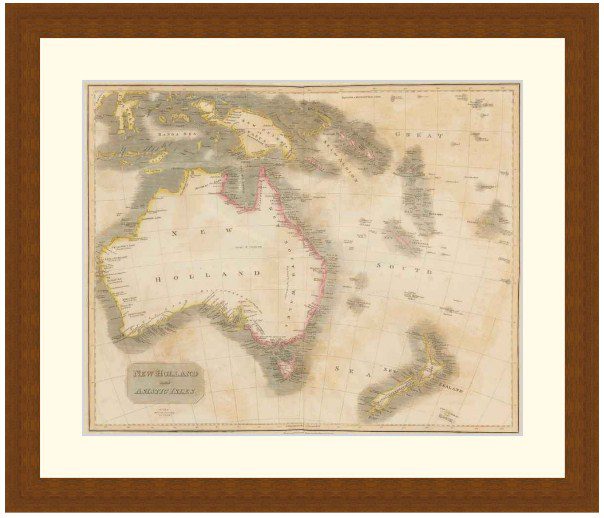

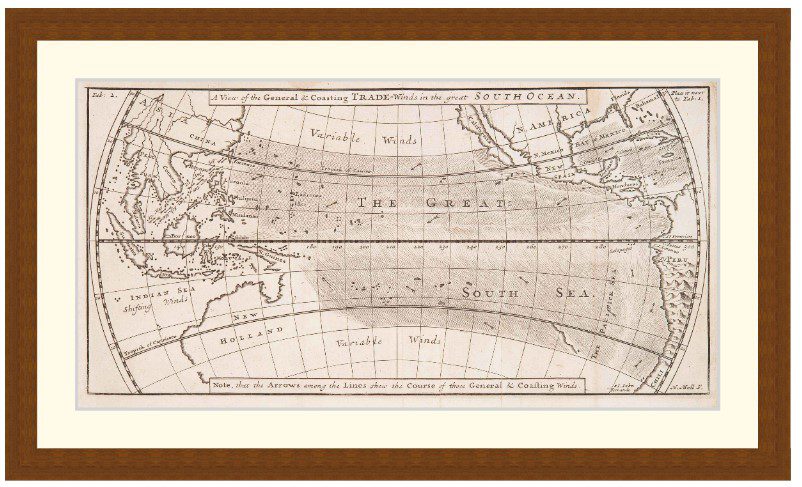

This was how the island stood when the first Europeans arrived. Papua itself first became known to Westerners through the travels of the Portuguese explorer Jorge de Menezes in the late 1520s. Goodenough and its neighbours, however, wouldn’t be discovered until the French naval officer and explorer Antoine Bruni d’Entrecasteaux sighted them in 1792. Between his death the following year and the late 19th century, the little archipelago, dubbed the D’Entrecasteaux Islands in his honour, would remain a mystery to outsiders.

It took generations of settlement and expansion in the South Pacific for more to come to light. But at last, in 1871, Captain John Moresby of the Royal Navy, commanding the paddle steamer HMS Basilisk in his search for routes between Australia and China, took a closer look. Naming the island and the mountain at its centre after a fellow officer, Commodore James Goodenough, he described how

“…gradually its woods give place to barrenness, and its summits stand bare and knife-edged against the sky. Mountain torrents dash down its ravines, and flash out at times from their dark green setting like molten silver.”

Moresby charted and named each of the islands (and would give his own to the capital of Papua New Guinea, Port Moresby), but didn’t press into the interior and moved on to complete his mission. But colonialism had arrived: Goodenough Island was known, and it wouldn’t be long until Europeans came again.

Tsukioka Butai: the Japanese Invade

In 1883, anticipating late-blooming German colonialism, the premier of Queensland independently (and illegally) announced the annexation of New Guinea as a territory of the British Empire. The move was ratified by the British government the following year, opening the territory to Australian activity. Few wanted to move to Papua permanently; instead, Imperial citizens came as missionaries, prospectors, and operators of copra (dried coconut) and cotton farms. Newspapers advertised prospects in economic ventures on Goodenough Island, including the availability of the inhabitants for work, with “over 10,000 natives on … plus over 30,000 nearby, ensuring constant, reliable labor at 1 [shilling] per day.”

And until 1942, that was the most the average Australian might have heard about its northern sub-colony. But in January of that year, war came perilously close to continents shores when the Imperial Japanese Army invaded New Guinea, beginning three years of some of the most horrific fighting in the Pacific theatre of World War II.

The bulk of the combat, and Japan’s forces, were on the main island. But Goodenough would soon play a small but critical role in the war. On 25th August, while the Kokoda Track campaign raged on Papua, 350 men of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s 5th Sasebo Special Naval Landing Force and a few naval engineers headed east from Buna on Papua and landed on Goodenough Island.

This detachment, called the Tsukioka Butai, or Tsukioka Force, after its leader, Commander Torashige Tsukioka, had orders to proceed to Taupota and cross the mountains to reach the northern shore of Milne Bay and seize the airfield which gave Allied planes the range they needed to strike deeper into the Pacific. What was meant to be a short layover on Goodenough Island would prove to be a nightmarish ordeal for the force when Australian coastwatchers spotted their transports on the west side of the island:

“During landing operations in the southwest corner of Goodenough Island on the 25th at 1040,” read a captured Japanese document, “we were raided by 10 enemy fighters for a period of 45 minutes, during which time all landing craft were set on fire and destroyed. A great deal of weapons, w/t equipment, food supplies etc which were in the boats were lost and 8 persons killed … and five seriously wounded. All medical supplies have been burnt.”

The fighters were Royal Australian Air Force Curtiss P-40 fighters from No. 75 Squadron RAAF, commanded by Squadron Leader Les Jackson. The Japanese were trapped, and would not reach their comrades at Milne Bay, helping ensure the predominantly Australian force at Milne Bay could repulse the Japanese invasion.

But the fight for Goodenough Island, Allied commander Douglas MacArthur had decided, had just begun.

The Battle of Goodenough Island

In 1942, while Japanese forces still posed a serious and wide-ranging threat in the Pacific, the strategic value of Goodenough Island was too much to overlook for either side. The western side of the island, where Tsukioka Force found itself without supplies or support, was covered in dense jungle. The grassy eastern side, however, offered excellent sites for airfields, which would allow whoever held them to threaten shipping and naval forces passing between Australia and the islands further north.

After No. 75 Squadron’s attack, Tsukioka Force marched south along the coast to take up positions between Galaiwau Bay and Kilia Mission. Two destroyers, the Yayoi and the Isokaze, were dispatched to rescue them, but Yayoi was destroyed by Allied aircraft and Isokaze was forced to abandon the attempt.

On 7th September, the attackers at Milne Bay were beaten off – the Australians dealing Japanese forces their first defeat on land of the war. Tsukioka Force was then the last Japanese force left in the area. They were in desperate shape: many were struck down with malaria, and with no rations, they scavenged potatoes from local gardens and salt from seawater. But having reached the southeast of the island, they were in a position to threaten the anchorages at Mud Bay, which would be vital to protect and supply the airfields planned for the northeast. Moreover, they were sustained through supplies delivered by submarine and airlift, with the wounded taken off the island.

The Australian response to the threat, codenamed Operation Drake, came on 19th October. Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Arnold, leading the 600 men of the 2/12th Battalion, an experienced Australian Imperial Force unit mostly made up of Tasmanians and Queenslanders, was ordered to invade Goodenough Island and eliminate the stranded Japanese marines there. Splitting his force in two, Arnold’s men advanced in a pincer movement around Taleba and Mud Bays.

The operation was troubled, beginning with a noisy and confused night time landing, after which both parties found the march over the hills in the area far more difficult than promised by the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit (ANGAU). To make matters worse, the two columns struggled to make radio contact with each other.

Over the course of a week, the 2/12th chased the Japanese westward, sustaining 13 men killed and 19 wounded to the Japanese’ 20 killed and 15 wounded. They took elaborate steps to convince the enemy that an entire brigade was on the island, burning fires large enough to cook for hundreds, setting out dozens of empty tents, and building dummy tanks, cannons, machine guns, and barbed wire emplacements using cloth, tin, wood, and vines.

Tsukioka Force was protected, in part, by the thick vegetation, which Arnold noted “took the sting out of the attack,” with Australians unable to see their opponents in some cases until they were mere feet away from them.

Finally, the smaller second detachment under Major Gategood returned to Mud Bay aboard the destroyer HMAS Stuart on 24th October. By 25th October, after two attacks on Kilia, Arnold’s force had run into well-prepared Japanese defences. When they advanced on these positions, they found them empty: Tsukioka Force had taken advantage of the Australians’ obstacles to escape to Fergusson Island, where they were collected by the cruiser Tenryu and taken to Rabaul.

The autumn months of 1942 were notable for a string of Allied victories in all theatres which, in hindsight, signalled the beginning of a slow turn of the tide. At Guadalcanal to the east, Allied forces were breaking Japanese strength, while the Second Battle of El Alamein marked the first major setback for Axis forces in North Africa. And while a small contribution, the Battle of Goodenough Island was nevertheless a step toward victory after the dark early days of the war.

An Air Node, Then and Now

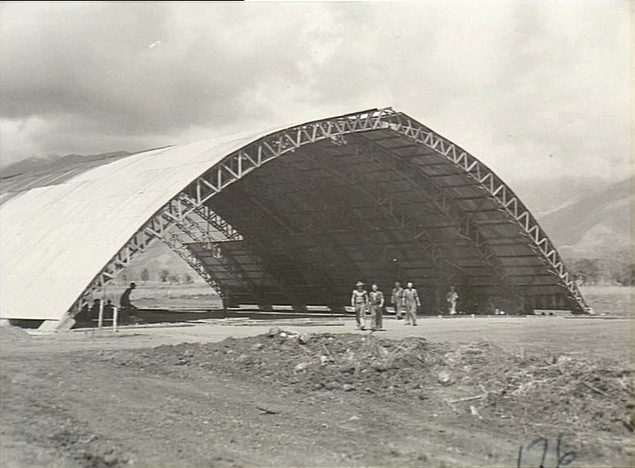

In December 1942, the 2/12th Battalion, freshly decorated with a unique battle honour for their efforts, departed Goodenough Island for Buna to take part in the ongoing fighting on the main island. After them came a small garrison and a substantial construction force. Australian engineers would build an anchorage at Beli Beli Bay and an airfield at the village of Vivigani capable of supporting fighters and bombers operated by squadrons of the RAAF. They were later joined by the headquarters of the United States Sixth Army, and further operations during the New Britain and New Guinea campaigns would be directed, supported, and supplied from the little island.

The base on Goodenough Island would be closed in late 1944, as Japanese positions further north collapsed and Allied forces forged ahead to the Japanese home islands. Air units moved onto better stations for the final push, and the island which had been so vital two years before finally went quiet. But the airfield at Vivigani would serve for decades more as a link to the island, an enduring legacy of the desperate days when the Allies struggled to withstand an ambitious Empire of Japan.

While the airfield fell into disrepair by 1993, prompting Talair, the Papua New Guinean airline then servicing it, to cease flights there, in 2021 the islanders restored the site and flights resumed. The airfield’s value may persist for new generations of Papuans, too: a recent proposal has been made to upgrade the airfield, establish a Papua New Guinea Defence Force station there, and keep Vivigani running as Goodenough’s best link to the world beyond its shores.

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 102

1. The ancient city of Salzburg was founded on which industry?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

Weekly History Quiz No.222

Who painted Luncheon of the Boating Party in 1881?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.