The Thirty Years War was a whirlwind in the centre of Europe that at some point between 1618 and 1648 swallowed up every European country before spitting them out again. Though nominally part of the wars of religion, it drew in its wide array of combatants for any number of reasons, ranging from national prestige to territorial gain. In fact, a combination of all three drew in an unlikely contender: Sweden.

Reading time: 5 minutes

By Fergus O’Sullivan

The Sweden of the 1600s was nothing like the peaceful, prosperous and egalitarian country it is today. It had colonial aspirations in the New World, as well as desires for a more prominent role in European politics. The main driver for all these ambitions was Sweden’s king from 1611 to 1632, Gustavus Adolphus.

Gustavus Adolphus

Also known as Gustav II Adolph in many English-language sources (a silly convention we’ll be roundly ignoring for the rest of this article), Gustavus Adolphus was one of the most prominent generals of his time, as well as being an avid reader and capable administrator. He was also a Protestant, though not a particularly fervent one.

When Gustavus Adolphus came to power, Sweden only owned a tiny piece of mainland European real estate in what are now the Baltic States and that was pretty much that. If he could snag some more land during the fighting, he could set himself and his dynasty up for centuries.

Building a Dynasty

Dynastic issues were most certainly weighing on the young Gustavus Adolphus. In the years before, his own family, the Vasas, had split into two. One branch ruled Sweden, while the other had become rulers of Poland-Lithuania, a huge state that ran all the way from modern-day Poland into the Baltics in the west and through Ukraine in the east.

This rival family made no bones about wanting to reclaim the Swedish throne and as a result they fought a series of wars with Sweden through the first three decades of the seventeenth century. These wars are separate from the Thirty Years War, though they did influence events greatly. The Swedes did well for themselves in these conflicts, expanding their territory in the Baltics considerably.

Besides such family squabbles, Gustavus Adolphus also fought wars against Denmark and Norway and even bumped heads with Russia. The result of all this fighting was that when the opportunity presented itself to enter the Thirty Years War, Sweden did so with plenty of hardened troops and experienced generals, as well as a strong economic base.

Entering the Fray

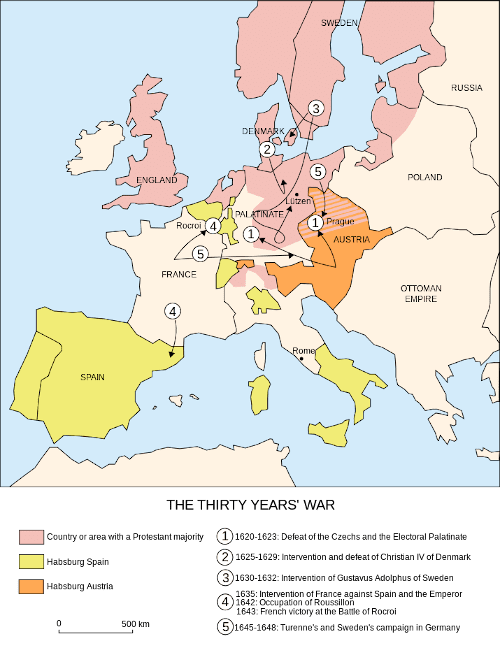

For the first twelve years of its duration, the Thirty Years War chugged along just fine without Sweden. The conflict had kicked off with the defenestration of Prague, which turned out to be a spark to a powder keg of inter-German rivalry as well as confessional infighting. In those first dozen years, armies had been raised and destroyed and several European powers had their noses bloodied.

It wasn’t just the countries directly involved that had suffered, either: while losses among the German princes and the Austrian empire were the greatest, Spain also had seen its efforts to bolster the Austrians end in a pool of blood. Another outsider, Denmark, had also seen its ambitions frustrated when it tried to make a name for itself.

The upshot is that when 1630 rolled around, the German soil had already been drenched in blood and the Catholic Austrians were in ascendance. Though the fighting clearly was far from over, right at that moment it seemed the old order would triumph eventually.

Poking the Bear

It was probably this slightly complacent mindset that drove Emperor Ferdinand of Austria to make a fatal mistake and promise aid to his kinsmen in Poland in their fight against Sweden. They had been losing their war against Gustavus Adolphus, and the Emperor had a few thousand troops with nothing better to do, so it probably seemed like an easy way to curry favor while also annoying another Protestant monarch.

What nobody seemed to have counted on was that Gustavus Adolphus wasn’t going to take this lying down: not only did he rev up his own war machine even further, bringing ever more tough troops to the theatre in the Baltic, an invitation from German Protestant princes to head up their alliance become very interesting indeed.

The Swedish Assault

Apparently, Swedish leadership was exactly what the German Protestant cause needed: soon after landing in Northern Germany in the summer of 1630, the combined Protestant forces swept through Germany, almost casually destroying their opposition. Gustavus Adolphus even made it as far south as Bavaria, on the Emperor’s doorstep.

However, the triumph would prove to be short-lived: though the Swedish troops were victorious time and again, their king’s luck would run out in November 1632 at the Battle of Lützen. Though the Protestants managed to beat back the feared Catholic commander Wallenstein, when the smoke cleared they found their king and champion dead from several bullet wounds.

His death was the end of the successful offensive and the Protestant forces made their way back to their homes to bind their wounds. Though the Swedes would stay in the war for a while longer, their vigour was gone and eventually they, too, would become just another combatant in a war that had taken so many already.

As for Sweden, as prosperous and egalitarian as it is now, there will always be a “what if” surrounding the dearth of their greatest king. Had he lived, would he have made Sweden into one of the great powers, with lands in Germany and colonies in the new world? We’ll never know.

Articles you may also like

A World War II battle holds key lessons for modern warfare

Reading time: 6 minutes

Between Aug. 7, 1942, and Feb. 9, 1943, U.S. forces sought to capture – and then defend – the Pacific island of Guadalcanal from the Japanese military. What started as an amphibious landing quickly turned into a series of massive air and naval battles. The campaign marked a major turning point in the Pacific theater of World War II. It also revealed important lessons about the nature of warfare itself – ones that are particularly relevant when planning for conflict in the 21st century.

Ireland and the Battle of The Somme

Reading time: 8 minutes

The Somme was the first great action by a British Army on a continental scale. It was the longest, bloodiest battle of World War One, a campaign lasting four and a half months, and fought over a twenty-mile front near the Somme. In February 1916 Allied commanders had decided to launch an infantry offensive there,

HMAS Nestor: The remarkable tale of an Australian destroyer

Reading time: 16 minutes

A convoy of 11 merchant ships escorted by 56 warships and submarines was making its way through “bomb alley” to deliver precious supplies to the besieged garrison on Malta. HMAS Nestor was just one of these warships assigned to protect this vital convoy. It was June 15, 1942, and this would be the last sunset the destroyer would ever see.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.