Escape from Greece

Reading time: 19 minutes

It began, as it sometimes does, with an old photograph.

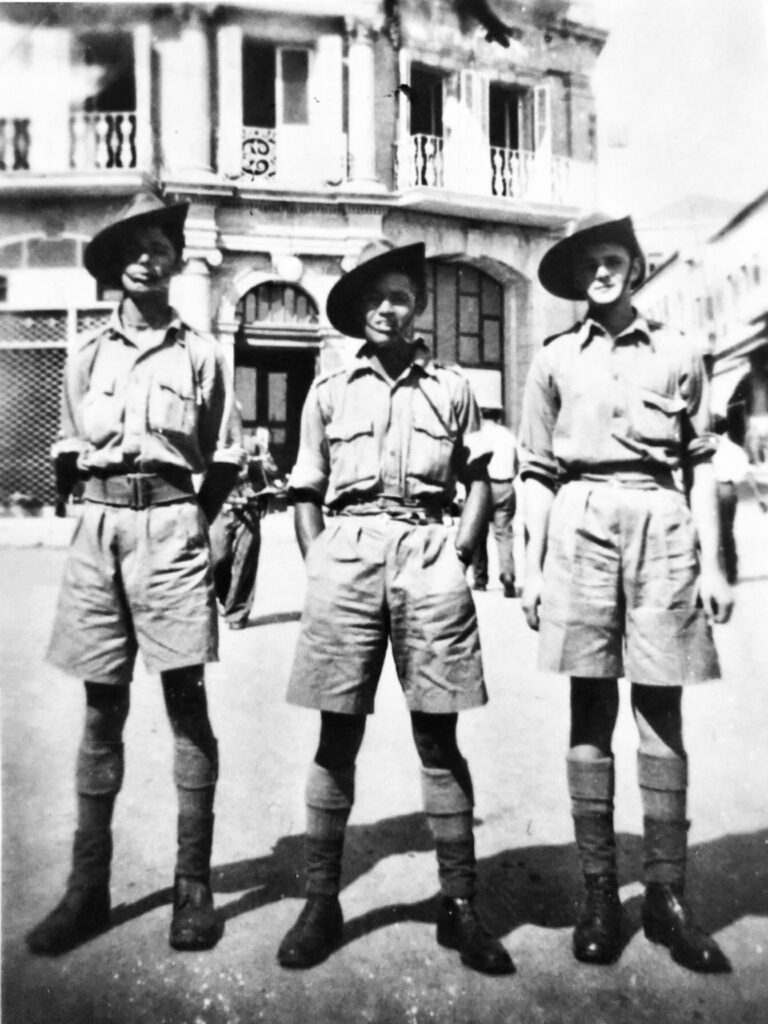

Three men dressed in khaki uniforms standing in front of an exotic facade in some distant land. The man in the middle – hands in pockets, slouch hat tilted at a jaunty 45 degree angle – is my uncle.

By Stephen Hutcheon.

John Greaves, or Jack as he was known, had served in WWII with the 2/2nd Battalion of the Second Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in the North African, Mediterranean and New Guinea campaigns.

I’d watched him march on Anzac Day and met some of his old comrades-in-arms. And when we met in person, there was that physical reminder of his war service. His gnarly left hand was missing a couple of fingertips as a result of a wartime injury which both shocked and secretly fascinated me.

One day in late 2019, I was looking at the photo and began to wonder where it was taken. I typed in a search term about Australian soldiers during WWII in the Middle East and it wasn’t long before I was able to identify the building behind the three diggers.

It was the Australian Soldiers’ Club in Jerusalem in what was the British Mandate for Palestine, which now encompasses Israel and the Palestinian territories. The photo was almost certainly the work of a photographer from the Matson Photo Service, which had a shopfront in that same building behind the three diggers on leave from their base in nearby Camp Julis.

Matson would have done a roaring trade in taking photos, processing film and selling cameras to the Australians, some 130,000 of whom served in the Middle East between 1940-42.

That discovery whetted my curiosity and although Jack, his wife and only son had long since passed on, his daughter-in-law was still living in the family home.

I come from a family with a predilection for hoarding life’s ephemera and luckily for me, most of Jack’s papers and photos (and even his uniforms) were still around. And when I finally got to rummage through Jack’s collection – and there was a lot of it – it was like stumbling into a pharaonic tomb.

From that beginning I was able to find some missing parts of Jack’s story and piece together the tale of a remarkable World War II escape that had never been told in full before.

From Shanghai to Sydney

What makes Jack’s story different from many of those who served in the same war was his mixed-race heritage. Born in Shanghai in 1914, John Robin Greaves was the eldest son of a Eurasian family which had made its home in the Chinese treaty port two generations before.

Jack grew up between two cultures. His Anglo-Scottish forebears came to China in the mid-19th century as traders and merchants. And in time they found local partners and started families.

In 1937, when Jack was aged 22, war arrived at his doorstep.

As a member of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps, he was mobilised to protect the foreign enclaves from Japanese incursion during what became known as the Battle of Shanghai. He would have witnessed enough brutality to make him realise his hometown faced a bleak future.

He wanted no part of that and decided to reboot his life in a quieter corner of the world.

Eighteen months later, he was aboard a passenger ship when it steamed into Sydney Harbour on a spring morning in 1939. With a suitcase of belongings, £50 in his pocket and not knowing a soul, Jack disembarked at Circular Quay.

“The East will never see me again,” he wrote to his sister Beatrice, my mother, from his new homeland.

To Palestine and beyond

But the war Jack tried to escape caught up with him. A year after his arrival, he enlisted at the recruitment office at Sydney’s Victoria Barracks. And a few months later he was sailing back out through Sydney Harbour on a troopship crammed with AIF recruits.

The destination was the British mandate of Palestine, where the recruits trained for combat – although they had enough time to duck into Jerusalem and do some sightseeing, as the photo in front of the Soldiers’ Club attests.

After a brief interlude in the North African campaign of early 1941, where Jack lost his fingertips on the eve of the Battle of Bardia, he spent the next few months convalescing in Egypt.

I found this photo of him in the Australian War Memorial archives. Taken by the renowned war photographer George Silk, it shows Jack on the far right, smiling as a group of injured soldiers pose with a couple of New Zealand nurses.

But by now, the British War Cabinet had turned its attention to the looming threat of a German invasion of Greece. Operation Lustre, as the Allies code-named it, was an ill-conceived plan to support the cradle of civilisation against the might of Hitler’s war machine.

READ MORE: THE BATTLE OF GREECE – AUSTRALIA’S TEXTBOOK REAR-GUARD ACTION

By March, Jack had recovered and rejoined his unit in Egypt and within a few days was boarding another ship, this time bound for Port Piraeus on the Greek mainland. After a few days, Jack’s unit was dispatched north to Veria Pass, high in the mountains of northern Greece.

By early April, the German invasion was underway and the entire Allied expeditionary force of some 60,000 men was soon in full retreat.

The Battle of Pinios Gorge

Pinios Gorge, also known as the Vale of Tempe, lies near Greece’s eastern coast. It has long been a strategic choke point used to defend the Greek heartland from invasion. And on April 17, 1941 invaders once again advanced towards it, opposed this time by Australians and New Zealanders.

Private Greaves was there as part of what the diggers called the PBI — the Poor Bloody Infantry. His mortar platoon was among those ordered to help slow the German advance, which threatened to cut off the main Allied retreat. To the north, a German Panzer division with infantry support approached the Anzac defenders. And from the north-west, elements of the 6th Mountain Division trekked over nearby Mount Olympus to outflank them.

“The valley was filled with the roar of rushing shells, the thunder of exploding mortar bombs, and the crackle of musketry echoing and re-echoing,” the New Zealand historian JF Cody wrote, describing the scene captured in this illustration by fellow countryman and war artist Don McNab.

The Anzacs proved to be no match for a combined tank and infantry assault supported by the Luftwaffe’s overwhelming air superiority. The battle extended into the following evening, and at dusk the German Panzers broke through, scattering the defenders.

“Orders were then given to us to retire, every man for himself,” Jack wrote in a report. “Close behind, a German tank seemed to be aiming its fire directly at me. Flaming onions [tracer rounds] flew past as I ran for my life.” He hopped into a truck heading south. But in the twilight, the Germans had cut off their escape route. They had only travelled a short distance when a single shot rang out.

“Then all of a sudden hell broke loose … The Jerries were in a perfect ambush … Machine guns, mortars and Very lights [flares] turned night into day for a few brief moments,” Jack wrote in his account of that evening. “Before I realised what had happened, Jerry was searching us for arms.”

Although the Germans were victorious, they had been delayed just long enough to allow thousands more retreating Allied troops to avoid capture. Nine days later, the Germans swept into Athens and following that, the rest of the Greek mainland was overrun.

Escaping the Germans

As enemy forces streamed south, Jack was marched north to Dulag 183, a notorious prisoner of war (POW) transit camp in the northern Greek city of Thessaloniki, or Salonika as it was then known.

Housed in a disused army barracks, the makeshift camp was already overcrowded when he arrived. And it wasn’t long before prisoners succumbed to diseases including dysentery, malaria and beriberi.

In a letter to his sister Beatrice, Jack described camp life as being a “hellish … nasty nightmare” where poor sanitation, meagre rations and backbreaking work became the norm. The POWs were attacked by what he described as “all species of body vermin ″ which covered their bodies and the rags that passed for bedding. “Life there was an unbelievable hell,” he wrote.

Jack biding his time while covertly assembling his own escape kit: a compass, a map and a set of civvies. He made several attempts to escape, but each time he was thwarted.

On June 25, he was among about 2,000 prisoners assembled on the camp parade ground in preparation for a four-day rail journey to more permanent camps in Germany and Austria. As they marched to the station, Jack knew that the train journey was his best and last chance to escape.

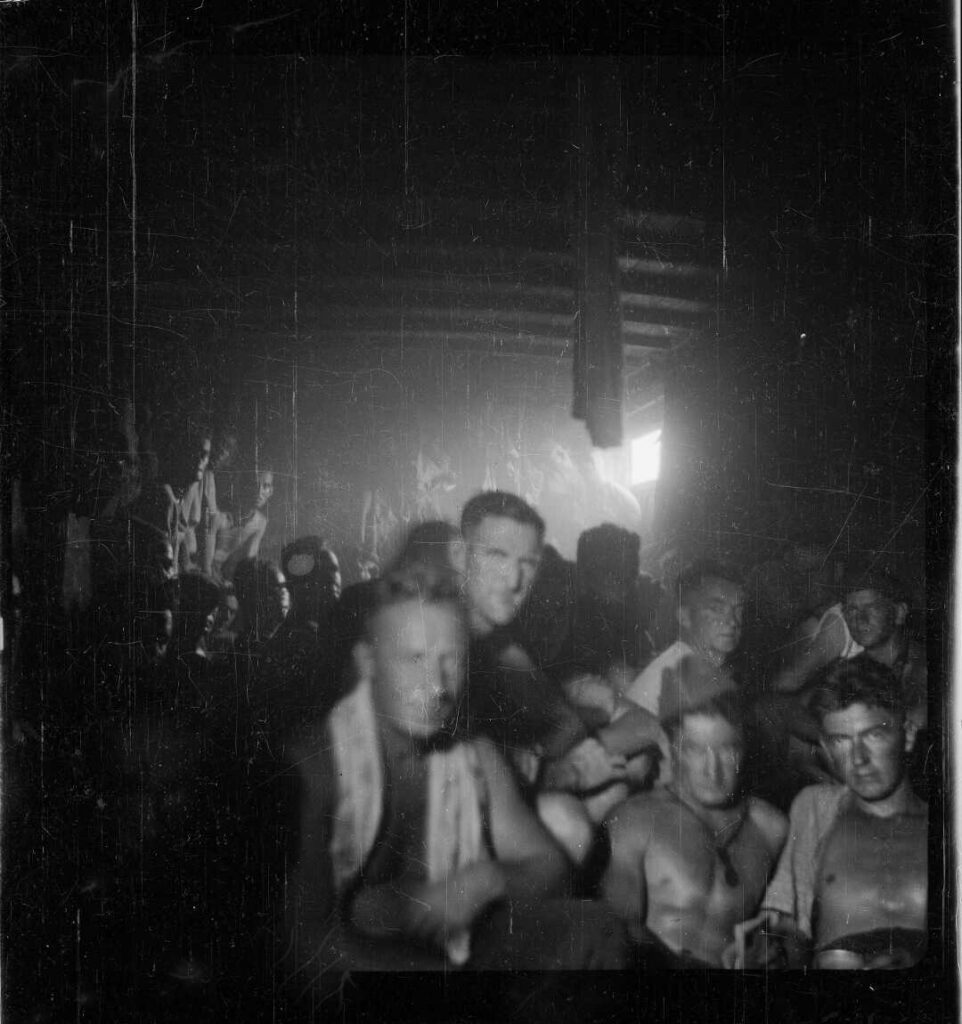

“Sixty men per carriage … and through a little hole two feet by one foot we had to relieve ourselves when nature called. Other than this there was no ventilation at all,” Jack recalled. With Greece now approaching mid-summer, the conditions were abominable.

This photograph taken in 1943 gives an indication of the conditions the men had to endure during the train journey.

Jack paired up with Private Tom Walker, a fellow digger from his battalion, and they made their way to the back of a carriage near the ventilation hole. At 7:00pm, the train pulled out of the station.

The night wore on and the train crossed the border into German-occupied Yugoslavia. Jack made his move, squeezing through the tiny window and onto the buffers and waited until the train slowed down going uphill.

The train stopped briefly and the guards fired a few parting shots into the bushes before resuming the journey without the two escapees. “Kaput! Kaput!” he heard them shout, as if to indicate that the bullets had hit their mark. As the pair scampered off into the moonless night, their plan was to head for neutral Turkey and then on to Egypt. But they weren’t out of danger just yet.

A trek through Greece

Jack and Tom spent the next six weeks navigating their way south from Yugoslavia back into Greece, following the path of the Vardar River valley before heading east towards the coast.

Jack kept a diary of his journey in a small, black notebook which he filled with tiny, cursive handwriting. It describes how the two men village-hopped their way through northern Greece, dodging the enemy and relying on the kindness of strangers.

“Forty five days on foot up hill and down dale, through swamps and rivers, in scorching sun and torrential rain. It was all in the game that we faced and then some,” he wrote.

It’s a journey of almost 300 km which today would take almost 60 hours to walk. But in 1941, the presence of Germans and their allies made every footstep a calculated risk for escapees weakened by disease, malnourishment and, sometimes, physical injury.

And it wasn’t just Greeks they met on their journey. Jack and Tom later crossed paths with three New Zealanders who were also on the run after escaping. And the five would eventually band together for the final, dramatic leg of their odyssey.

A Kiwi contingent

The first of three Kiwis they met was a 35-year-old lance corporal in New Zealand’s 25th Battalion called Bill Kerr. The Aussie soldiers, Jack and Tom, come across him in mid-July in the town of Olympiada, a small fishing village in the Macedonia region of northern Greece.

Bill was a sheep farmer from the North Island before he enlisted. In Greece his unit saw action in late April on the ancient battleground of Thermopylae, surrendering on April 24 after he had run out of ammo and was surrounded by tanks.

“Prison life didn’t appeal to me; so I made plans to escape,” he wrote in a letter to his family that was published in a New Zealand newspaper in 1941. “I managed to get some rope and in the middle of one night I lowered myself from a balcony, climbed under barbed wire and was away like the wind.”

Remarkably, he remained on the run for the next three months mostly on his own. And — despite being tall, fair-haired and blue-eyed — remained undetected by the Germans and their allies.

On July 18, just days after his meeting with Jack and Tom, Bill ran into fellow Kiwis, the Brewer brothers, Owen and Frank.

Owen was a private in New Zealand’s 21st Infantry Battalion. Frank, who had enlisted in Sydney, was a gunner with the AIF’s 2/1st Field Regiment. Owen was captured on Anzac Day at Kissos, a village in central Greece, and taken to the same prison camp at Thessaloniki where Jack was being held.

In late April 1941, Frank Brewer was one of about 10,000 Allies waiting to be evacuated from the southern port of Kalamata when he was captured along with hundreds of other Allies left stranded there. Frank and the other POWs were eventually marched north, arriving at the camp in Thessaloniki in June where he was reunited with his brother Owen.

In early July, the two brothers decided to make a break for it. Exploiting a gap in the fence created by an earlier escape attempt, they wriggled their way through a maze of wire “inch-by-inch in constant fear of being caught”, according to Owen’s escape report. It was, he said, “one of the longest hours of my life”.

“We took the risk of a quick death rather than a slow one by starvation and exhaustion,” Frank wrote in a letter to his sister, excerpts of which were published in a New Zealand newspaper.

Two weeks later, the Brewer brothers ended up in Olympiada, where they bumped into Bill Kerr. From there the three POWs trekked south toward the peninsula of Mount Athos, where in late July the five escaping Anzacs teamed up for the final leg of their escape from Greece.

The final dash for freedom

The Mount Athos peninsula rises from the aqua waters of the Aegean Sea, a mix of rocky coves and forested slopes crowned by a 2,000-metre-high peak known in Greek as the Holy Mountain. Since the Middle Ages it has been home to some 20 Orthodox Christian monasteries.

It was here that many Allied escapers and evaders fled in the aftermath of the disastrous Greek campaign, not only because it was a departure point for neutral Turkey, but also because of the sanctuary they believed the monks would offer.

Jack and Tom had spent a few weeks recovering from their arduous trek in the monastery of Dochiariou on the western shore of the peninsula. By the time the Brewer brothers and Bill Kerr arrived on the peninsula in search of a way out of Greece, Jack and Tom had already been trying to obtain a boat to take them on the 165km journey across the Aegean to Turkey.

Eventually, the five Anzacs converged on the monastery of Iviron on the east side of the Athos Peninsula. Frank Brewer, who had picked up a good command of the language, haggled a deal that saw the monks agree to supply a boat and crew in return for some cash up front and a promise to pay £50 when the war was over.

At 10:00pm on August 4, 1941, the escaping POWs pushed out from shore aboard a 6-metre-long traditional boat called a caique.

After a treacherous journey, they beached on the Turkish mainland on August 8, just south of what was known as Cape Helles and the mouth of the Dardanelles Strait – names that would have been very familiar to the Anzacs of 1915.

They were given food and water by the local villagers, but Turkish soldiers who arrived later wanted the Anzacs to leave and mocked-up a firing squad to scare them away. They were sent back out to sea, only to return the next day.

Their persistence finally paid off when a Turkish officer arrived and the escapees convinced him to allow them to stay.

Under the Geneva Convention a neutral power was obliged to allow escaping prisoners to transit through its territory and back to their bases or homes. But that process took another five weeks of diplomatic argy-bargy before the five were finally given the green light to leave Turkey.

That day came around on September 18 when the five, and a number of other escapees, boarded the British-registered freighter SS Destro at Iskenderun, a port in southern Turkey near the border with Syria.

They were heading back to their units in Cairo to complete a successful escape – a feat known colloquially as a “home run” and one accomplished by fewer than 1 per cent of British and Commonwealth troops captured by the Germans during WWII. After an uneventful voyage, the Destro docked at Port Said Egypt’s northern coast on October 6, 1941.

There is this final photo of the escapees taken on the deck of the Destro. Eight men in ragtag outfits posed for the camera, squinting in the bright Mediterranean sunshine. Bill Kerr and Frank and Owen Brewer are there.

But among the other faces in the photo, there’s no Jack, no Tom and, frustratingly, no explanation or even clues as to why in any of the documents and personal accounts I have obtained. But the diggers were definitely on the same ship.

“At long last we have reached our objective and carried out our duties as soldiers. We have no regrets about the hardships, disappointments, and often dangers, which were our lot for the past four months,” Jack wrote about the day of his return.

It had been 170 days since his capture.

READ MORE: THE BATTLE OF CAPE SPADA: THE AUSTRALIAN NAVY PROVES ITS METTLE

Epilogue

All five men survived the war. Owen Brewer and Tom Walker were repatriated home, classified as medically unfit to continue service. Owen tragically took his own life in 1970. I never found out what happened to Tom.

Bill Kerr was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal and went on to fight the Germans in North Africa. Injured and captured, he was sent to Italy and then later Germany before being repatriated home by the Red Cross in 1944. He passed away in 1984 aged 79.

Frank Brewer was awarded the Military Medal and later mentioned in dispatches. He joined MI9, a special forces unit, which returned to occupied Greece to assist the resistance and escaping Allied soldiers and later served in New Guinea, rising to the rank of captain. He died in 2004 in his mid-80s.

Jack Greaves went on to complete two tours of duty on the front lines in New Guinea. He never made it past the rank of corporal and his role in planning and executing the escape was never officially acknowledged. He passed away in 2003 aged 85.

Listen to a podcast episode that tells this incredible story

This project commemorating the service by Victorians in the Mediterranean theatre of WW2 was supported by the Victorian Government and the Victorian Veterans Council. Sign up to the newsletter at the bottom of the page to be notified when the next article in this project is released.

Articles you may also like

The Battle of Greece – Australia’s Textbook Rear-Guard Action

Retreat doesn’t always mean defeat, sometimes it can be a victory to withdraw in good order and deny your enemy a total victory. This is was the outcome for the allied forces in Greece during April 1941, thanks in part to textbook rear-guard actions fought by Australian units, which allowed 50,732 men to escape the grasp of the advancing superior Axis force. But why were Australian units involved in Greece in the first place?

Remembering the Victory at Bardia

Just over 80 years ago, Australian forces fought their first major battle of World War II. Bardia, a small town on the coast of Libya, some 30 km from the Egyptian border, was an Italian stronghold. The Australian troops occupied Bardia, defeating the Italians in a little over 3 days. Australian veteran, Phillip Wortham, simply […]

The Battle of Cape Spada: The Australian Navy Proves Its Mettle

Reading time: 9 minutes

The Battle of Cape Spada was a short, violent encounter on the 19th of July, 1940 where the cruiser HMAS Sydney of the Royal Australian Navy sank one Italian cruiser and severely damaged another off the coast of Crete. In this article, we go over the events of that day, as well as what life was like for the crew of the ship.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.