THE AUSTRALIAN FLYING CORPS, 1917–18

Reading time: 8 minutes

By 1917, the men of the Australian Flying Corps’ No. 1 Squadron had been fighting in the Middle East for almost two years. Now Australia’s airmen were ready to join the allies’ broader campaign in the Great War.

Because Europe was the main theatre, the next three AFC squadrons to be raised—Nos. 2, 3 and 4—were designated for the Western Front. They arrived in England for additional training between late 1916 and early 1917. Supplementary courses for aircrew and mechanics were conducted at a number of English military depots and civilian institutions (including Oxford University), and covered such subjects as rigging, engines, weapons and wirelesses. Four AFC training squadrons were then established in England: Nos. 5, 6, 7 and 8.

Flying training was a dangerous business. Royal Flying Corps (RFC) statistics show that on average every trainee destroyed six undercarriages and wrecked two aircraft ‘completely’. Arthur ‘Harry’ Cobby and George Jones, who were to become major figures in Australian aviation history, both crashed in England and were lucky not to have been killed. By the end of the war, there were 25 Australian graves in the cemetery near the training base at Leighterton in Gloucestershire.

No. 2 Squadron was the first AFC unit to arrive on the Western Front, where it was integrated into the RFC. Brilliantly led by Major Oswald Watt, the squadron distinguished itself on the first day of the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917. Flying their DH5s only metres above the trenches because of heavy fog, the Australian pilots bombed and strafed enemy troops, gun batteries, fortifications and supply trains. By the end of the day, six of the squadron’s 18 aircraft had been shot down and another was missing. When the battle was at its fiercest, the squadron was visited by the commander of the RFC on the front, Major-General Hugh Trenchard, who described the Australians as ‘really magnificent’.

Nos. 3 and 4 Squadrons arrived in France shortly afterwards, the latter allocated to fighter and attack tasks, the former to reconnaissance and army liaison. Because of their artillery spotting and photographic roles, No. 3 Squadron’s RE8s were prime targets for German fighters, often being attacked by as many as 12 aircraft. Despite the RE8’s modest performance, the Australian pilots and observers managed to shoot down 51 enemy aircraft, a remarkable achievement.

No. 4 Squadron was to become the AFC’s most successful fighter unit in terms of enemy aircraft destroyed, claiming 199 kills to No. 2 Squadron’s 185. That slender margin may have been due in part to No. 4 Squadron’s having been equipped from the outset with one of the war’s outstanding fighters, the Sopwith Camel, whereas No. 2 Squadron had to make do with DH5s until rearmed with SE5as after the Battle of Cambrai. No. 4 Squadron also benefited from having in its ranks the AFC’s two leading aces, captains Cobby and E.J.K. McCloughry.

Harry Cobby was the archetypal fighter pilot: courageous, dashing and good-humoured. A bank clerk from Prahran, he joined the AFC in 1917 and by the end of the year was in France. He scored his first kill on 4 February 1918; and on 20 March he and another pilot intercepted five aircraft from von Richthofen’s Flying Circus and shot down three. In a brief period in July, Cobby scored double victories on the 9th and 14th, and four kills on the 19th. In between those dogfights, Cobby, like his colleagues, strafed and bombed German trenches and supply lines.

On one occasion while patrolling alone Cobby was attacked by 16 Fokkers. With his guns jammed, he threw his Camel into a series of desperate manoeuvres that enabled him to break away and escape by hedge-hopping back to allied lines. His aircraft was so badly shot up that when he landed it split apart, leaving him unconscious but unscathed. Another time, his seat was shot out from under him and he had to fly home holding on to the fuselage to save himself from falling out. Once he landed his Camel in the middle of the Australian lines and, still dressed in flying helmet and boots, rode the winner of an impromptu horserace the diggers were holding. He then took off and resumed his patrol.

By the end of his tour, Cobby’s reputation was such that he was leading formations of up to 80 allied aircraft. He finished the war as the AFC’s top ace and a national hero, having shot down 29 aircraft and 13 balloons.

By early 1918, four Australian Flying Corps units were on active service: No. 1 Squadron in the Middle East, and Nos. 2, 3 and 4 Squadrons on the Western Front.

AFC crews in the Middle East were also attached to a special air unit formed to protect Colonel T.E. Lawrence—the legendary Lawrence of Arabia—and his force of 30,000 Arab irregulars, who were suffering rough treatment from German bombers. Lawrence was thrilled by the nonchalant bravery of Lieutenant Ross Smith, whom he described admiringly as ‘an Australian, of a race delighting in additional risks’.

Allied air power reached its zenith in the Middle East in September 1918 during the Battle of Armageddon, a campaign planned to achieve the final overthrow of the Turks. Having first established air supremacy, the allied airmen attacked the enemy furiously, causing terrible carnage. During one engagement, 10 aircraft from No. 1 Squadron decimated a trapped force of 3,000 troops, 600 camels and 300 horses, repeatedly bombing and strafing terrified men and animals. The battle ultimately resulted in the destruction of three Turkish armies and the capture of Damascus, events which precipitated an armistice on 31 October.

Mention must be made of the theatre’s outstanding AFC personality, Richard ‘Dicky’ Williams. A thin, intense man whose high forehead and penetrating gaze accurately reflected his probing intellect, Williams was strong-minded, confident and an excellent organiser. He was also a courageous pilot, decorated with the DSO and OBE and twice mentioned in dispatches. Williams was promoted to command No. 1 Squadron after only a year in the Middle East, and in June 1918 he was given command of one of the two wings comprising the Royal Air Force’s Palestine Brigade, a considerable achievement for a ‘colonial’. Subsequently the first chief of the Royal Australian Air Force in 1921, Williams remains the greatest figure in Australian military aviation history.

On the Western Front, the most notable event occurred in July 1918, when the AFC participated in the Battle of Hamel, arguably the first genuine application of joint (air and land) warfare, planned by the brilliant General John Monash.

Conclusion: a revolution in military affairs

Popular images of air combat in World War I have been shaped by flickering films and sepia photographs, in which chivalrous amateurs seem to play out an exciting new sport remote from the squalor of the trenches. In reality, the war in the air was ruthless, cruel and, ultimately, professional.

Casualty rates were shocking, reaching 88% in some squadrons for extended periods, and averaging more than 50% for the war. The life expectancy of new pilots on the Western Front was three weeks. At the direction of the British air commander, General Hugh Trenchard, aircrew were not allowed to wear parachutes, a decision which condemned those whose aircraft were shot up to the horrific choice of either burning alive or jumping to their deaths. Contrary to popular notions of chivalry, once the early excitement of the war had been replaced by hard cynicism, it was common for downed airmen to be strafed and killed by enemy pilots.

Nor was there much understanding of the physiology of flying. Sustained flight above 3,000 metres in an open cockpit in winter subjected men to severe stresses, and aircrew frequently died from the bends or in spasms and fits after landing.

Those squalid happenings were offset to some extent by brilliant technical achievements. In August 1914, aircraft performance was abysmal, and it was not uncommon for pilots to experience an engine failure a week. By 1918, fighters could climb to 6,000 metres in 43 minutes and cruise at 7,300 metres, impressive figures which necessitated oxygen systems and heated flying suits. Other innovations included engines that had five times more power than their predecessors and were vastly more reliable, air-to-ground wirelesses, bomb racks, automatic cameras, multi-engine bombers, and illuminated navigation beacons that flashed in Morse code to guide crews at night.

Technical advances were complemented by the rapid development of sophisticated doctrine. Roles such as control of the air, close support, interdiction, reconnaissance, army and fleet cooperation, anti-shipping strikes and, most significantly, strategic bombing, were all familiar to air force commanders by 1918, as were complex tactics for coordinating the activities of very large formations of fighters and bombers.

The rise of air power between 1914 and 1918 represented the 20th century’s first revolution in military affairs. The men who were to lead the RAAF when it was formed in 1921 were exposed to that revolution, and received a severe professional education. In that context, the achievements of the AFC were heroic in their own right, and constituted a precious legacy for the RAAF.

This article was originally published in The Strategist.

Articles you may also be interested in

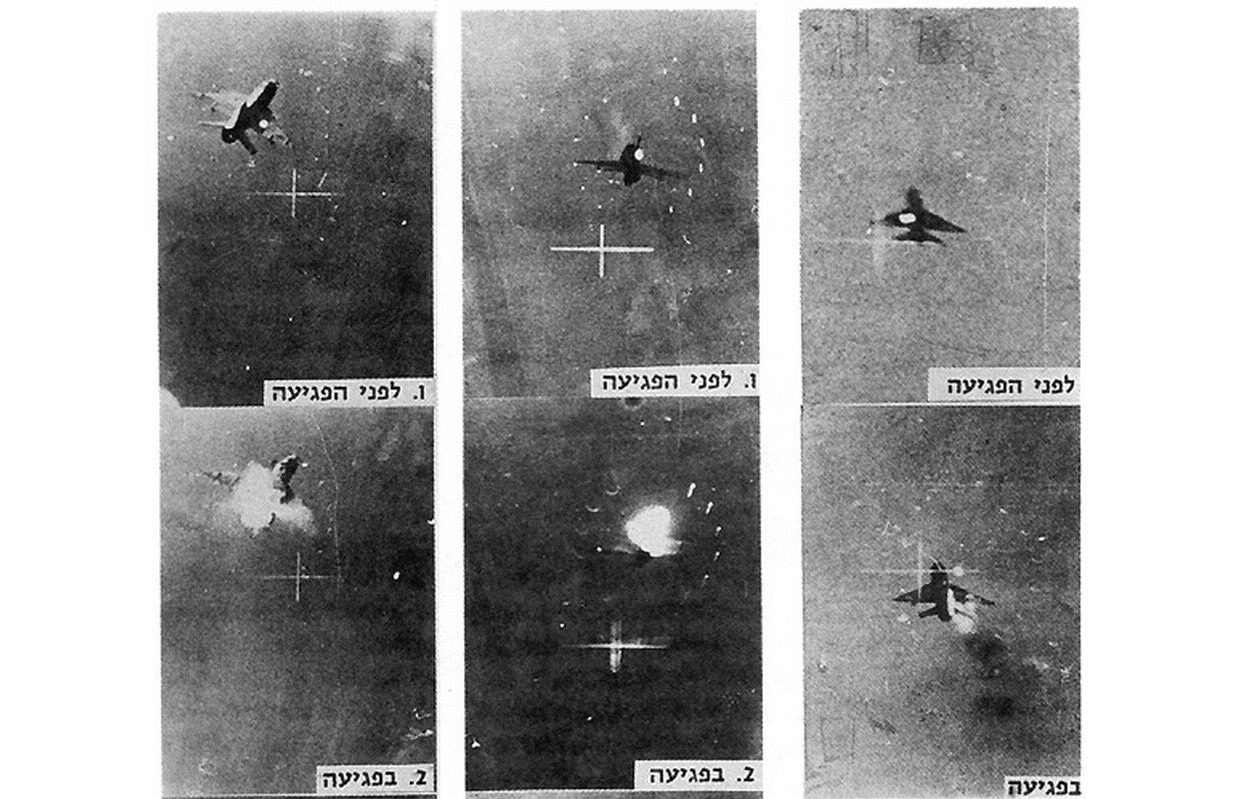

51 years ago: Israel won an air battle, and lost the War of Attrition

The Israel Air Force drew the Soviet expeditionary force in Egypt into a perfect, successful ambush, but pride was the country’s downfall, in the long run. For Israelis, this weekend marks the 51st anniversary of a famous victory. But then as now, hubris may be our worst enemy. On July 30, 1970, the Israel Air […]

Remembering the Victory at Bardia

Just over 80 years ago, Australian forces fought their first major battle of World War II. Bardia, a small town on the coast of Libya, some 30 km from the Egyptian border, was an Italian stronghold. The Australian troops occupied Bardia, defeating the Italians in a little over 3 days. Australian veteran, Phillip Wortham, simply […]

Australia’s first action in the Pacific in World War II a valiant catastrophe

Just before midnight on 7 December 1941, Flying Officer Peter Gibbes stepped off the train at Kota Bharu on the coast of northeast Malaya after a long, tiring journey up the peninsula from Singapore. Gibbes, an airline pilot in peacetime, had been newly posted to the Royal Australian Air Force’s 1 Squadron, which in the […]

The text of this article is republished from The Strategist in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.