Explore the story of the Roanoke disappearance. And the latest findings and theories that have brought us a bit closer to understanding what might have happened.

By Caitlan Hester

One hundred and fifteen English colonists deserted Roanoke Island between 1587 and 1590, forever lost to the historical record. To this day no one knows exactly why they abandoned the colony or where they went.

Archaeologists, however, believe they’ve found intriguing evidence that can shed light on this 430-year-old mystery.

The Roanoke Voyages

In the 1500s, shortly after Columbus voyaged to the Americas, all of Europe was clamouring to stake their claim on the new continent.

England began an attempt at the first permanent English settlement in what became the modern-day United States in 1584. England was in competition with Spain, and the East coast of the U.S. was a good site for privateers and pirates to intercept Spanish ships.

The New World was also believed to be rich in natural resources that England could mine.

The First Roanoke Voyage

Queen Elizabeth I placed Sir Walter Raleigh, famed soldier and explorer, in charge of the mission.

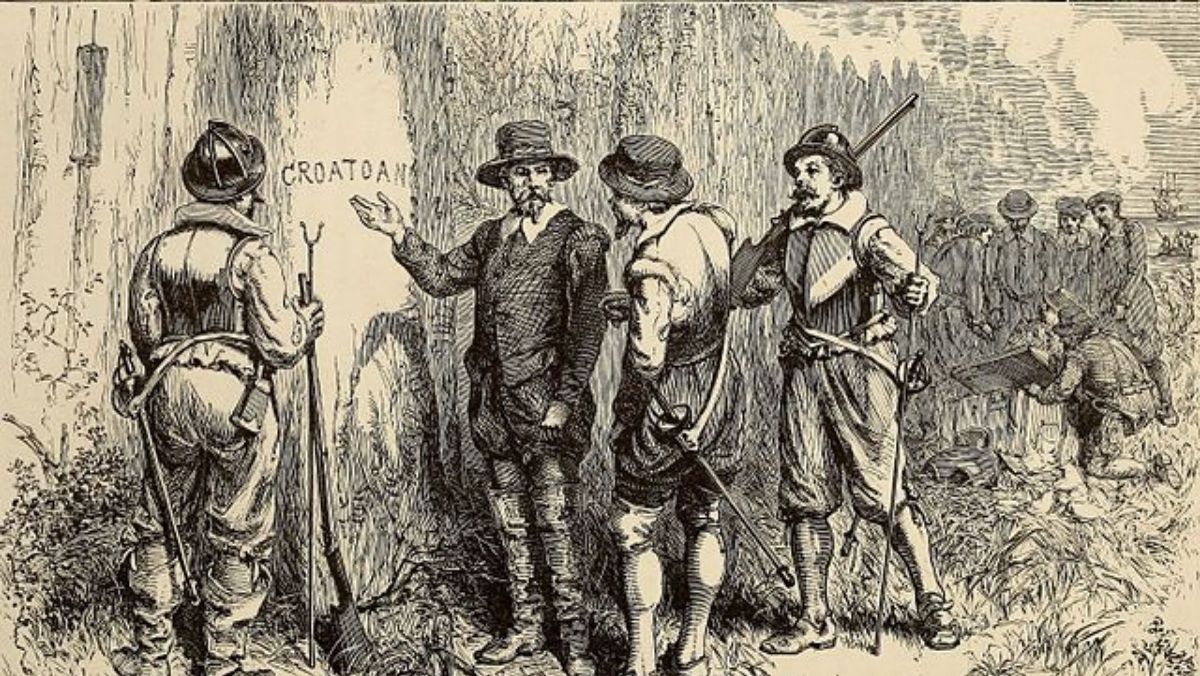

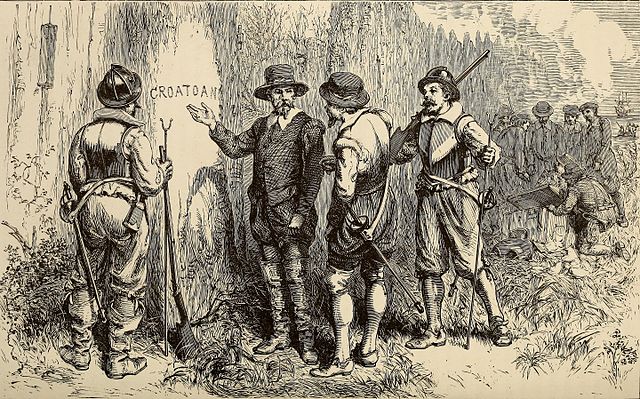

Author: John Cassell

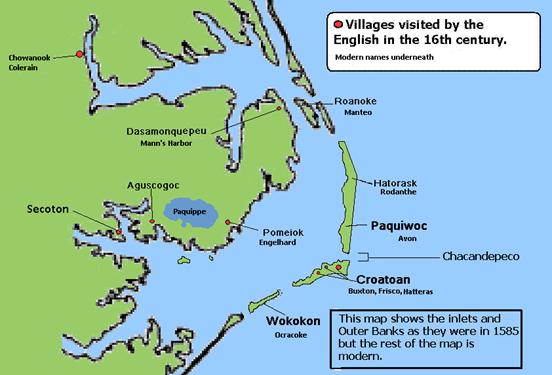

The first voyage was a reconnaissance mission. The explorers involved travelled along the East coast and identified Roanoke Island as an ideal location for settlement. Roanoke Island is now located in Dare County, North Carolina.

The Second Roanoke Voyage

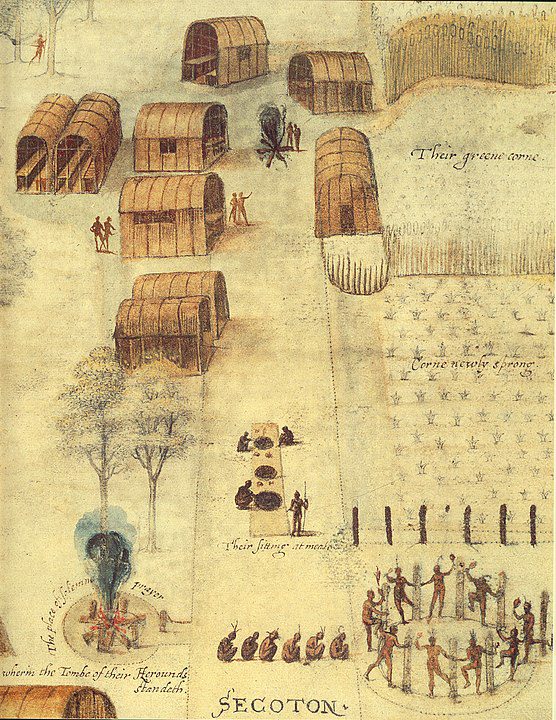

A year later, in 1585, Raleigh sent a second voyage to Roanoke. This party consisted of 100 scientists, soldiers, and miners – all men.

The second voyage was a total failure. Supplies ran out, winter set in, and tense relationships with neighbouring Native Americans escalated, leading to the colonists murdering the local, native chief.

They abandoned the fort and colony, unaware that two English supply ships would arrive less than a week later. These supply ships, upon finding the site abandoned, left 15 men behind to hold the fort in the name of England.

The Third Roanoke Voyage

For his third attempt, Raleigh recruited 115 men, women, and children – mostly middle-class Londoners.

He appointed John White, painter and illustrator, as the governor. White travelled to the New World accompanied by his wife and pregnant daughter.

The third voyage didn’t intend to settle on Roanoke Island. They had decided to settle in the Chesapeake Bay area this time. But first, they stopped to check in on the 15 English men left by suppliers. While they were there, they were pressured by their pilot to stay on Roanoke Island.

The Anglo-Spanish war was breaking out and their pilot was a Portuguese privateer. He was anxious to get back to intercepting Spanish shipping, a more lucrative role during war-time.

The colonists were uneasy about remaining at Roanoke because they found the 15 men preceding them had been killed by natives.

Yet their pilot left them no choice, so they remained on Roanoke Island. Governor White decided to return to England with the pilot, to resupply. But when White got to England, he became stranded by the war.

When White was finally able to return to the settlement three years later in 1590, he found it abandoned.

Governor White’s Return

Not only had the village been abandoned, but everything had been taken. White found the village surrounded by wooden palisade walls, an indicator that the colonists feared an attack. But they found no slain bodies or graves.

Carved into one of the palisade logs, White found a single word in capital letters, CROATOAN. He and his search party also discovered the letters CRO carved into a nearby tree.

Two Possibilities for the Missing Colonists

White was not immediately distressed. He was certain that the word ‘Croatoan’ indicated the missing colonists’ location.

Croatoan was the name of a Native American tribe located around 50 miles south of Roanoke. Croatoan also happened to be the name of the island that these natives inhabited – modern-day Hatteras Island in North Carolina.

If he could not find them there, he would also search 50 miles inland of Roanoke.

Before White departed three years before, the settlers decided that if they should need to move, they would go 50 miles inland to an agreed-upon location.

The colonists had also agreed that if they left the colony due to hardship or force, they would leave a carving of a Maltese cross to communicate their misfortune. Finding no cross, White was confident he would find them alive.

A Failed Search Party

Before White could begin the search for his wife, daughter, grandchild and some 112 other English colonists, his crew was hit by a strong storm.

The storm, possibly a hurricane, damaged the ships and an anchor was lost. White’s rescue mission was forced to return to England where White was never able to raise enough funds to return to the New World and search for his family.

Raleigh was forced to give up on his American-settlement venture. This task would be carried out by the London Company shortly after, when they established the first English settlement in the U.S. at Jamestown, Virginia in 1607.

Clues and Speculation

Evidence suggests that the Spanish were gathering information about the Roanoke colony because they feared the English would create a pirate base. Some historians believe the colonists could have been attacked by the Spanish.

Perhaps the colonists had been slain by Natives seeking revenge for their dead chief, murdered during the 2nd Roanoke expedition. They had already killed the 15 Englishmen from the supply ship.

But if the colonists had been slain by the Spanish or the Native Americans, why weren’t there any bodies?

The Most Likely Answer – Native American Assimilation

About 20 years after White’s last departure for England, Captain John Smith of the Jamestown colony received a clue from neighbouring Native Americans. They told him that men wearing European clothing were living inland, west of Roanoke.

Smith organized search parties but never located the colonists.

One hundred and eleven years after the famous disappearance, an explorer named John Lawson travelled to Croatoan Island in 1701. While there, native peoples told him that “several of their ancestors were white people”. He observed that many of them had grey eyes, uncharacteristic of Native Americans at the time.

As English colonies began to grow in North America throughout the 1600s and 1700s, it was common for men, women and children to be welcomed by Native Americans as members of the tribe. Smaller Native American societies supported the idea of safety in numbers.

Some tribes captured colonists and taught them their ways. Most colonists who were captured preferred to stay with their tribe, even when given the chance to return to English colonies.

There is also evidence that some tribes killed young adult men and spared women and children. As well as evidence of tribes capturing colonists and selling them to other tribes as slaves.

Looking at what we know from the historical record about later colonists and their complex relationships with natives – The people of Roanoke likely succumbed to (or welcomed) a similar life among the natives.

Splitting Up and Survivor Camps

Archaeologists look to the soil and the historical record for answers, but they also use comparative observation in human behaviour.

A popular theory today is that colonists – troubled by possible famine, disease, harsh weather, and the uncertainty of White’s return – went their separate ways.

Mark Horton, an archaeologist at the University of Bristol tells National Geographic, “This is typical in situations like shipwrecks. Order breaks down and you end up with several survivor camps.”

It’s very possible that the survivors of Roanoke split up: some moving inland, some moving to Croatoan Island, and then assimilating with various Native tribes.

The Archaeological Evidence on Croatoan Island

In 1993, a hurricane exposed evidence of a Native American village on Croatoan Island. Horton has led a dig on the island every year since 2013. His teams have uncovered European artefacts mixed with Native American artefacts at the centre of the village.

Author Ken Lund.

The early Elizabethan artefacts include the remains of a gentleman’s dress sword, pieces of European copper, lead shot, the barrel of a gun, a piece of drawing slate, and a lead pencil.

These artefacts could be evidence of the Roanoke colonists on Croatoan Island. Or they could be evidence that the Croatoans plundered Roanoke Island.

The problem is that these artefacts are found mixed with later Elizabethan pottery and beads. It’s impossible to say with certainty if these objects belonged to Roanoke colonists or if they arrived later through trade.

The Archaeological Evidence for an Inland Escape

Governor White had created a watercolour map of Roanoke which is now at the British Museum.

In 2011, Brent Lane, a heritage economics professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, noticed light patches on a copy of the map.

Professor Lane pushed the museum to explore those patches on the original. After three months of pushing the British Museum, they obliged Lane’s requests and placed the painting on a light table.

They were shocked at what was revealed – a fort located about 50 miles inland of the Roanoke colony, exactly where the colonists told White they would go.

This exciting find ignited archaeological digs to locate the Roanoke colonists’ inland fort and survivor camp.

Although archaeologists have unearthed exciting finds, like early Elizabethan brass and pottery, nothing has proved conclusive enough to link these artefacts to the Roanoke colonists with certainty.

Could DNA Provide the Answers?

To test what John Lawson said in 1701 about Croatoan Natives with white ancestors, researchers could potentially use DNA testing.

The theory is that they could find living North Carolinians with DNA similar to that of the Roanoke colonists. If living relatives exist, that would mean that there were Roanoke survivors that went on to have children.

Researchers have begun collecting DNA from the people of North Carolina. The problem is that they do not have modern English DNA from anyone related to the Roanoke colonists to compare it with.

Perhaps future excavations at one of these three dig sites will unveil a 16th-century English burial. If the burial has recoverable DNA, such a finding could be used to determine if there are living ancestors of the Roanoke colonists.

Cultural Implications

Interestingly, the colonists of Roanoke weren’t considered ‘lost’ in 1590. John White and the others from the failed rescue mission continued to believe that they were on Croatoan Island (modern-day Hatteras Island) or at the inland escape 50 miles west of Roanoke.

It was, by and large, assumed and accepted that after never receiving a supply ship from England, the colonists had assimilated with Native American tribes to survive.

This is how the storey goes for around 240 years.

Until the 1830s, when the way we tell the storey starts to change. This is around the time when you see President Jackson’s Indian Removal Act and black slavery nearing its peak.

Historians in the U.S. began to prefer to say the colonists ‘disappeared’ and shroud the storey in mystery, rather than say the colonists likely intermarried and assimilated with natives.

The people of the 1830s who were breaking treaties with natives and keeping black slaves didn’t have any use for assimilation as part of their origin story.