Reading time: 5 minutes

In our documentation of eyewitness accounts of Australians in the Med during WW II, we have mainly focused on the experiences of frontline troops and sailors, men who faced enemy fire and worse. What about people a little farther back from the front, those who took care of the wounded?

By Fergus O’Sullivan

We dug through the Australians at War Film Archive, a massive trove of interviews with Australian veterans, to find stories of nurses who served in field hospitals in Palestine and Egypt as the Second Battle of El Alamein raged in October and November of 1942.

All the women interviewed were members of the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD), a civilian unit that provided care for wounded military personnel. Though often untrained, they shipped off in their hundreds to the Middle East, and later the Pacific, to help out the war effort.

First Stop, Palestine

Upon arrival in the Middle East, all the VAD staff were sent to hospitals in Rehovot, between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, for training. However, as the war heated up, Jean Parry from Scottsdale, Tasmania recalls that Polish staff soon took over the Rehovot location and most of the Australian nurses and VAD staff were sent to the 6th Australian General Hospital (AGH) in Gaza, close to the Egyptian border.

Gaza was a base hospital and we staged with the 6th AGH and the men went to Kilo 89 […] and we were there and working in the wards and what not and they had decided that the 7th [AGH] would be a mobile hospital at that stage and they would use some of the staff.

However, not much was happening in that area at that moment, and Mrs. Parry states that the 6th AGH was sent up to Syria to assist in Australia’s war with France for a few weeks. However, as Rommel’s Afrika Korps got closer to the Nile, they again moved south and set up a small field hospital in Busili, 13 miles from Alexandria, on the coast. As a field hospital, it was fairly rudimentary, recalls Mrs. Parry:

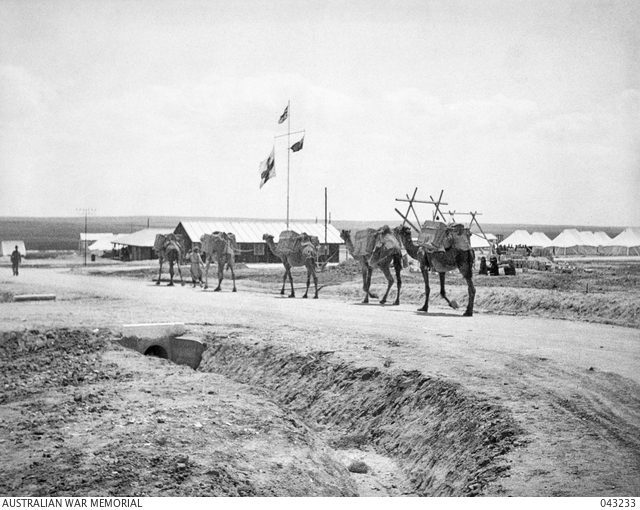

It was a desert site and sand all around and it was we were all under canvas. All the wards were tented wards. Sixty bed wards with on concrete blocks with a nurses’ centre in between which was a wooden building and then the tents either side and except for we had a couple of wooden buildings which were for the more serious cases and apart from that it was all canvas. We all slept in tents twelve by twelve tents and which had been camouflaged and again four to a tent and we slept on stretchers.

As the staff set up, they knew they wouldn’t have long to wait, says Mrs. Parry:

It had been an English hospital and our hospital had taken over so there was a lot of work to do to clean up and settle up the way we wanted and then we were getting some casualties there at that stage but not really until the 23rd of October […] o on the 23rd we were waiting outside our tents and sure enough we could hear the noise of the guns and the light in the sky from the battle even though it was a long way away because it really was loud and we knew then that we we’d be called upon to work as we’d never worked before […] the next night they the ambulances came.

Life at Busili

The nurses and VAD staff had been preparing for the start of the battle, and Mrs. Parry recalls exactly what was expected of her, even 60 years later:

[…] they drove the ambulances to our hospital where the sisters and our medico examined them and their and each patient had a tag pinned to him with his name and number and his injuries. And then of course the stretcher-bearers were there to take them to the appropriate wards and we were already in the wards, where the beds were made up, and we had been well instructed of what to expect and what we had to do.

And the stretcher-bearers would start at one end of the ward and put that patient there and they of course were straight from the battlefield with their dirty blood-stained and mud-stained uniforms and they were put on the beds and we then had to get them out of their […] uniforms and sponge them, put them into a clean pyjamas and get them into their beds ready for the medical officer […] to examine them and decided what was going to happen with them.

And then of course, when we had time we gave them something to eat and drink, but because we couldn’t do that first because we didn’t know whether they had to go to theatre or go to the plaster room or what not, we had to wait until the [medical officer] saw them before they we gave them something to eat.

Dorothy Dowson from Perth in her interview emphasized the stress of the work, saying it was “harrowing” how an empty ward could be filled up with wounded men in a matter of a few hours. When asked if it was tiring, she had this to say:

Oh absolutely exhausting. So much so, of course you weren’t allowed to sit on the bed of the patients but nobody cared. They’d probably go and see somebody they knew that was wounded and nobody minded sitting, the nurses sitting on the beds. But you’re too tired to go back to the mess or anything.

When asked if there were any breaks during her 14 to 16-hour shifts, she smiles grimly.

You’re just so busy you kept going. Someone said “Oh it was terrible you know I went and cried” I said “Well we didn’t have time to cry”, you know you’re just too busy doing things. And it would be silly if we all went into the kitchen and cried.

Behind the front

Not that things were peaceful back in Gaza, either, recalls Jessie Timcke from Adelaide had stayed behind at the 6th AGH. Their job was to take in the wounded after they had been initially treated at forward hospitals like the one at Busili.

Well, you got up in the morning. I can’t remember whether it was seven o’clock or something, to start, or half past seven. And you were on a roster. And you’d stay in that ward, perhaps, the rosters used to be done once a week or something like that. And you had to see where you are. And you wouldn’t always be going to the same ward either. You’d be in ward seven one day and then off to somewhere else. And I did that for a while. Of course, you did night duty as well. And that was all night you had to be on there. And that was a bit of a thing because they had a little part of the big ward just to a kitchen and another one where the sisters were, and it was so dark and miserable in the middle of the night.

As relaxed as she seems telling this, she does point out how much work was in the running of a hospital if you take away all the modern medicines and equipment we now take for granted.

I don’t think anything in those days was anything like the standard today, medicine or hospital treatment. A lot of it was still fairly makeshift, and didn’t have antibiotics and things like that either. So a lot of it had to, over there, be improvised or done by hand; all the sterilising and everything.

Things were even better for Jean Oddie who grew up in Western Australia, who had stayed in Jerusalem, never even having been to Gaza. She’s one of the few interviewees who worked in actual brick-and-mortar building, rather than tents. However, as VAD staff, her work was more menial than the other women in this article.

We had all sorts of different kinds of duties depending on what type of ward we were in, whether we were in medical ward or a heavy surgical ward, it depended. We had to take, not charge of, but we had to be very active in the kitchen when the meals were coming in. We had to make sure it was kept clean and we had to make all the drinks for the different patients. We had to make all the different meals for the patients who couldn’t eat and what came through. We made beds and washed, we did full sponges and backs, we took temperatures and we helped in the surgical wards, we helped with the dressings. You would get the stuff ready, we washed the bandages and gave them to the men to roll up. We did all sorts of things.

We were there to take the place of the male orderlies who were then supposed to go back into the army to the front line. I think we did, we always had an orderly on anyway to do the big bathroom jobs, with the men to take the men to shower them if they had to be showered especially, and things like that. We always had one orderly on. We helped the nurses with whatever they asked us to do.

Of nurses and men

One of the things that pops up in all the interviews is the esteem the women had for the men they treated, and the respect and admiration they received from their patients. Mrs. Parry describes the “mateship” of men who had shared trenches and foxholes together.

They never complained and you they’d come in and they’d say, “Has so-and-so arrived? Oh he was really badly hurt.” They were more concerned about their mates of how they were and the ones who were still there and still fighting than what they were about themselves [there was] this just wonderful feeling of companionship […] and then sometimes they’d hear a voice and they’d say, “Oh that’s my mate there. Can I can you put him next to me?” and the stretcher-bearers would wangle it around and move A to B and so two mates would be together.

Mrs. Dowson says much the same:

And how marvellous they all were helping each other and then we were flat out with nobody to help. Because it was so stretched, but the boys themselves, anyone that could get up and help would, and all they wanted to do was get back to see how there mates were.

Even though the troops were used to roughing it in the company of men only, they did, according to Mrs. Parry, show the staff all due respect:

They were wonderful. The men really gave us so much respect. Nobody, you didn’t hear any of the men swear, they didn’t tell dirty stories. If a group of the men this was even were there talking together and […] if they were perhaps telling a story or someone swore they’d always go, “Shh, shh here comes nurse, here comes sister,” and if anyone swore well the others would really attack them. Nobody swore. They really respected us and we again gave them the care and attention that they wanted but that was what happened in those days. You didn’t hear dirty stories, you didn’t hear bad language.

Mrs. Oddie had a more poignant story, one that shows that the nurses and VAD staff were dealing with more than just physical wounds:

They were wonderful. They were brave. They were so thoughtful of their fellows who, other fellows who had been wounded. They could pick out a malingerer quick as a flash and he was ostracised. They were very good to us; we girls, they looked after us. I had a problem one during the Battle of Alamein. It was just after the beginning and a poor young soldier came in. The wards were chaotic. The wards were full. He leapt out of bed and pushed me into the wall, luckily it was canvas, and, “You bloody Hun.” And all the ones who could leap out of bed and save me because the poor little fellow, it had been such a terrible experience for him; he was off his mind temporarily. That was… They cared for us a lot.

They did what they could to help us and they were a rough tough lot, not rough tough, a nice, rough tough. […] A pleasure to nurse, sadly they were there to be nursed, but by and large you got your funny ones as well as difficult ones, but this was what they were like.

Even with stories like this, though, it’s clear that the interviewed women are still proud of what they could do for the soldiers, and of their service. Once the Middle East had quieted down a little, many of them would go on to serve in the Pacific or even at home, in Australia, until the war’s end.

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 164

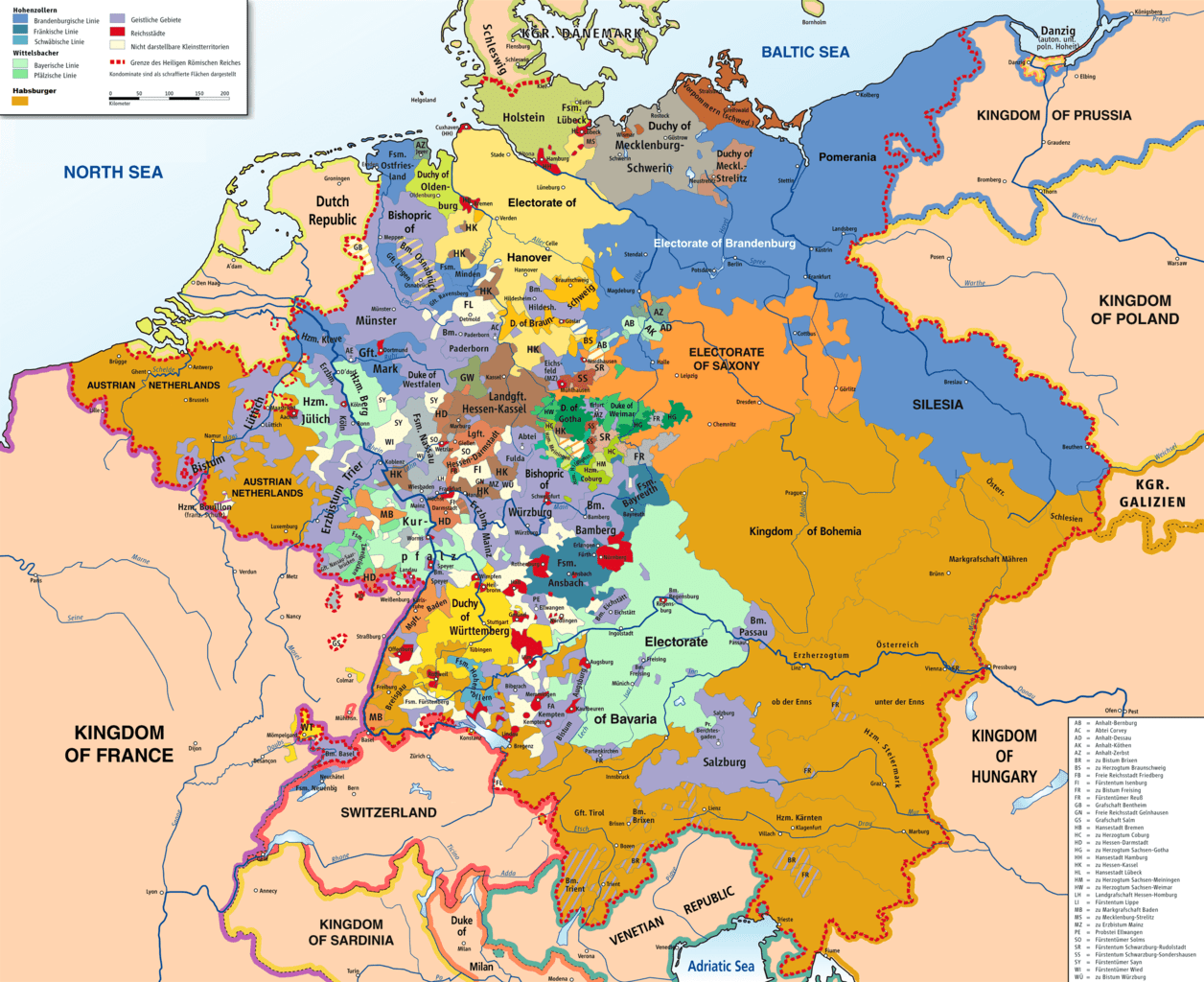

1. In the years leading up to 1871 how many states were unified to become the modern country of Germany?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.