Reading time: 11 minutes

For a country just over a century old and whose national image is one of tough, independent action, some of the most active individuals involved in Australian nation-building have not been soldiers or stockmen but writers. Keith Murdoch was one of these, and his career and its consequences still echo throughout Australia and the world today.

By Morgan WR Dunn

A pioneering journalist (and political intriguer), Murdoch was one of the chief authors of the ANZAC myth. But before this was his legacy, Murdoch was one of the most active and prolific Australians of the First World War and the early Federation. Long mythologised himself, he was also a complicated and sometimes villainous figure.

THE YOUNG REPORTER

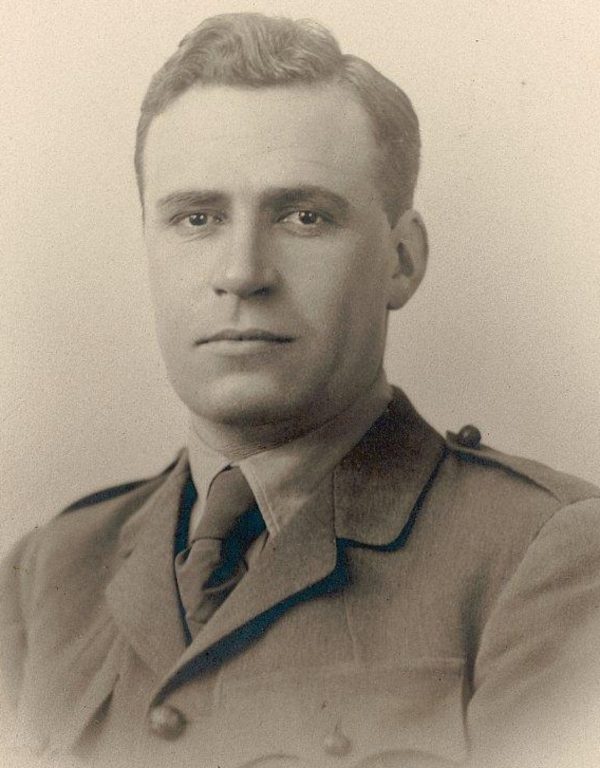

Keith Arthur Murdoch was born in 1885, the eldest son of Scottish-born Patrick, a Presbyterian minister, and Annie Murdoch. His childhood wasn’t without hardship: the family was socially influential but poor, and young Keith struggled in school because of a stammer. But he was also taught by his uncle, Walter, that “clear written English is the bedrock to success,” and when Walter became a reporter for The Argus, one of the young country’s most important newspapers, his nephew was inspired to follow in his footsteps.

His father’s social connections helped Keith make his way: as soon as he’d left school in 1903, Melbourne newspaperman David Syme gave him a job as a reporter at The Age, chief competitor to The Argus. Over four years, Murdoch built up a wealth of experience and valuable connections, and by 1908, he’d saved enough to answer the magnetic call of London, heart of the Empire.

A year spent abroad allowed Murdoch time to study at the London School of Economics, write, and to visit the United States. Along the way, he came to broaden his acquaintances with writers and editors in Fleet Street and New York, giving him a sense of the power and influence that a newspaper could wield.

Murdoch’s travels left him poorer in pocket, faithless (living in London had ended his Presbyterianism), and altogether wiser about the limitations of newspapers and the men who ran and wrote them. His stammer still remained (it had cost him a job at the Pall Mall Gazette), but now he was determined to be a journalist. He knew it wouldn’t be easy, noting “Journalism certainly is precarious. But I’m young and strong and should not fear. My whole desire I think is to be useful in the world, really useful to the highest causes. And surely if I keep that ambition untarnished I should get my chances.”

THE GALLIPOLI LETTER

Murdoch returned to Australia in 1910, just in time for the fourth federal election. Securely employed as a parliamentary reporter for The Age, his family’s Scottish roots and his new position allowed him to become close with Andrew Fisher, leader of the Labor Party, who won the prime ministership that year.

Fisher lost by a single seat at the 1913 election, but regained the premiership in 1914. By now close to the center of Australian politics, Murdoch, who had moved to Hugh Denison’s tabloid The Sun in 1912, was already in the habit of spying for Fisher. When the First World War broke out, Murdoch narrowly lost the vote to secure the post of official correspondent to the Australian Imperial Force. But in early 1915, Denison offered him something almost as good: the position of managing editor of the United Cable Service in London, which supplied Australia’s media with global news.

On his way to London to take up the position, Murdoch stopped over in Egypt, then a British protectorate and the launchpad for the AIF. Because colonial forces came under strict Imperial control in wartime, not even Fisher knew where Australian troops were or what they were doing.

The answer was Gallipoli. A peninsula in the European part of Turkey, Gallipoli was the centrepiece of a strategy championed by Winston Churchill which aimed to suffocate the Ottoman Empire and remove it from the war. Sir Ian Hamilton, commander of Imperial forces in the effort, maintained strict censorship of the effort, but when Murdoch visited Anzac Cove in September 1915, he became determined to reveal the truth.

Presented as a gallant attack in glowing official reports, the reality was that the Gallipoli campaign was a disaster. Tens of thousands of Imperial troops, including the bulk of Australian forces, were trapped with their backs to the Mediterranean amid disease and determined Turkish resistance. While taking this in, Murdoch befriended Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, a British journalist who’d written the original glowing reports of the Gallipoli landing.

Ashmead-Bartlett had quickly become disillusioned with both the management of the campaign and with censorship. He wrote a letter to British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith detailing his concerns and, since Murdoch was already on his way to London, begged his new friend to deliver it for him.

On his way, Murdoch was intercepted and arrested by Hamilton, who confiscated Ashmead-Bartlett’s letter. But Murdoch was by now determined to expose the truth, and upon arriving in London, he had several meetings with British leaders at the highest levels and began writing a 25-page letter, a recreation of the impressions he and Ashmead-Bartlett shared, for Fisher and Asquith. This letter, while revealing that “Australians now loathe and detest any Englishman wearing red,” also served Murdoch’s desire to praise his country’s first wartime army.

“I could pour into your ears so much truth about the grandeur of our Australian army,” he told Fisher, “and the wonderful affection of these fine young soldiers for each other and their homeland, that your Australianism would become a more powerful sentiment than before.”

The Gallipoli letter was a triumph. Aside from a few misimpressions and errors, the facts Murdoch presented were basically accurate, and the letter succeeded in vindicating the AIF while damning Hamilton and the entire campaign. Hamilton was recalled to London in October, his career finished. And, thanks in part to Murdoch’s efforts, Australia’s army was salvaged from Gallipoli in January 1916. The war was far from over, and the survivors of Gallipoli, along with a somewhat declining stream of volunteer replacements, had years of grueling combat ahead. But Murdoch, his reputation made, was now a serious contender in wartime press politics. In 1916, Andrew Fisher, by then the Australian high commissioner, had little access to Prime Minister Billy Hughes when he visited London. Murdoch, as a recognised shaper of public opinion, had no such trouble.

ATTACKING THE GENERAL

1916 was the year that Murdoch began to throw himself into his role as a political influencer outside of the newsroom. He was particularly active in promoting Hughes’ conscription referendum. When this vote failed, Murdoch, by now a keen observer of the Anzac mind, pointed out that a key reason why the “wonderfully generous” men of the AIF had voted against conscription was that they “did not like compelling others to enter the hell they are in.”

In other ways, Murdoch was far less perceptive. Australia’s WWI experience was a laboratory for national consciousness, one of the strongest examples being the proposal for an Australian Corps – the combination of all five Australian divisions into a single command under Australian leadership. As the idea gained steam in 1917, Murdoch, in favour of the idea, was also becoming accustomed to “playing courtier and journalist at the same time.” Not content to report the news, he was trying to influence events in real time, and when it came to the Australian Corps, he picked an unfortunate fight.

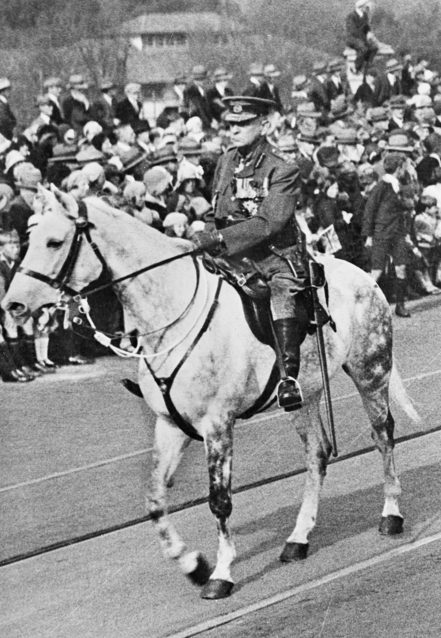

When the Australian Corps was finally realised, Lieutenant General John Monash was appointed to lead it. Monash, an engineer and longtime militiaman, had proven to be Australia’s most effective field commander; his leadership of the 3rd Division had so impressed British generals that they saw him as a natural choice for corps command. But his path to high rank hadn’t been smooth: Monash’s German-Jewish ancestry was a constant target for the anti-Germanism and widespread anti-Semitism of the day. He’d even been subject to rumours that he was a spy for the Germans.

These prejudices did nothing to harm his reputation with Hughes’ cabinet. But Murdoch and Charles Bean, the journalist who’d won the position of official correspondent at the war’s beginning, felt otherwise. Major General Brudenell White, who’d never held a field command, was the man for the job, they felt, even as White himself supported Monash. Murdoch assured Hughes that he spoke for the men of the AIF, so when the prime minister planned to visit the Western Front, he came with a mind to dismiss Monash.

When he arrived, Hughes interviewed Australian Corps staff members and ordinary soldiers alike. He discovered that, far from being a “pushy Jew,” as Bean described him, Monash was an exceptionally capable general and well-loved by the men under his command. To replace him as Murdoch and Bean wanted would be to deal a serious blow to the morale and confidence of the AIF. Monash himself proved unmoveable: “I want you to know,” he told Hughes, ‘I will not voluntarily forgo this command.”

The campaign to unseat Monash, who would lead the increasingly skillful, and increasingly exhausted AIF to the war’s end, had failed. Murdoch would remain in Europe through the remainder of the war and beyond, but he would not repeat the success he’d achieved with the Gallipoli letter.

FOUNDING AN EMPIRE

Murdoch spent the post-war years shoring up his social standing and establishing a press empire. He went from chief editor to managing director at the Melbourne Herald, married in 1927, was knighted in 1933, and steadily invested in newspapers around Australia. In 1928, he became involved in Adelaide’s press scene when he bought The Register, a failing local paper, and eventually took over the larger Adelaide News. Murdoch eventually established a monopoly over Adelaide news media, and by 1931, while cutting wages at his papers in order to weather the Great Depression, admitted that he was happy to leave his own salary cut because “I am such a big shareholder that dividends matter a lot more.”

When he died in 1952, he left behind a wife, Elisabeth, with four children and a sizable fortune in shares in newspapers around the country. Much of this wealth evaporated as his affairs were settled, but News Limited, the company which owned the Adelaide paper, remained in the family’s possession. This was to be the inheritance of Keith’s only son, Rupert, who used the paper as a base with which to expand across Australia and New Zealand, and to purchase The Sun and News of the World in Britain.

Podcast episodes about Keith Murdoch

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 93

1. In Medieval Europe what was referred to as ‘Outremer’?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

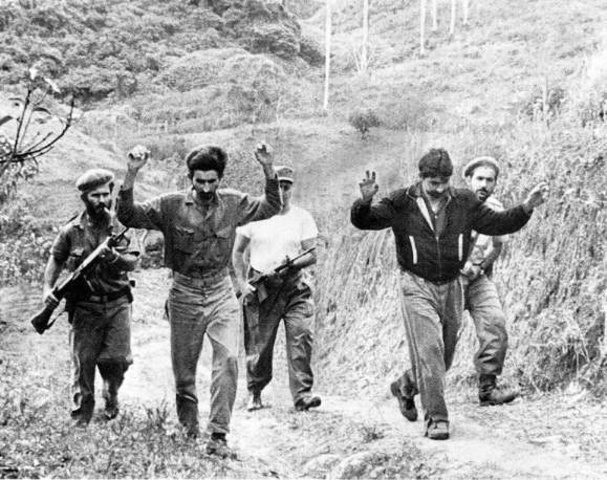

Hubris and Miscalculation: The failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion

HUBRIS AND MISCALCULATION: THE FAILURE OF THE BAY OF PIGS INVASION By Michael Vecchio The threat of Nazi villainy had been defeated, however another authoritarian threat rapidly placed over half of Europe behind what Winston Churchill called an “Iron Curtain”. The Soviet Union’s aggressive brand of Communism startled much of the Western world, but perhaps […]

General History Quiz 162

1. Which English royal line provided kings from William the Conqueror to Henry I?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.