Reading time: 13 minutes

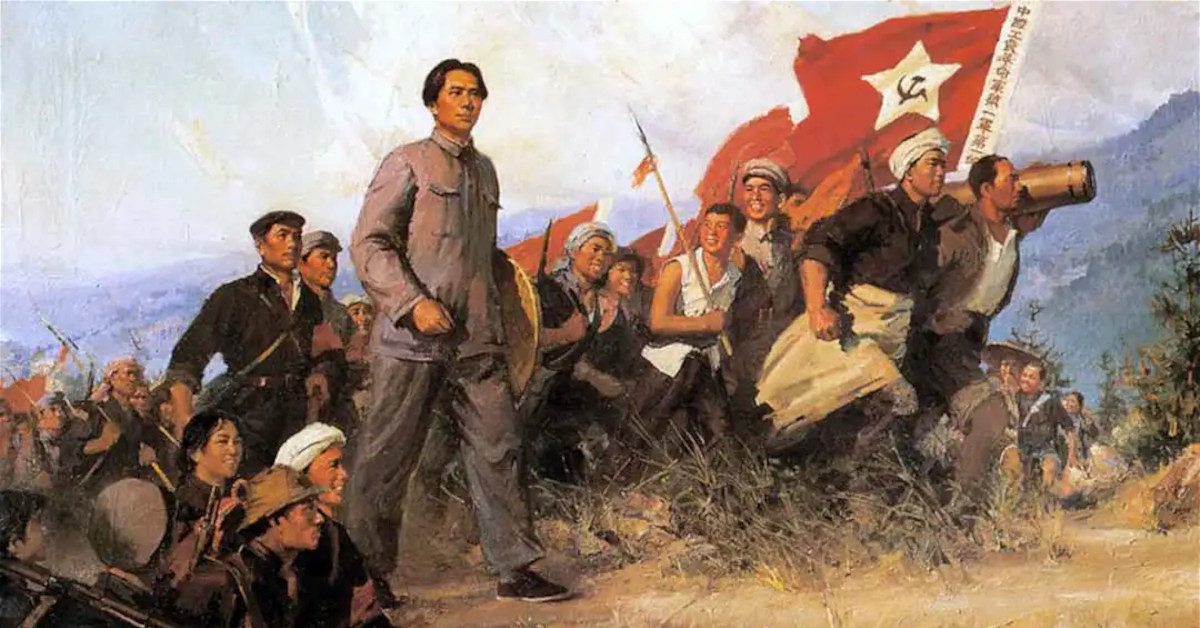

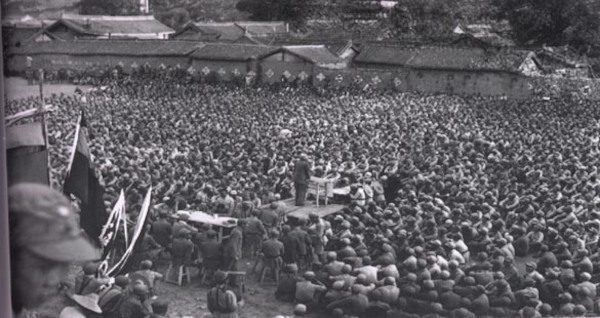

On 21 September 1949, Mao Zedong took to the podium in Huairen Hall, Zhongnanhai, a former royal residence in Beijing, to announce that “the Chinese people, comprising one quarter of humanity, have now stood up.”

These striking words were all too appropriate for the moment: for Mao it represented the end of a quarter-century journey to the pinnacle of his own party and finally his country – a journey which began with the Long March.

By Morgan WR Dunn

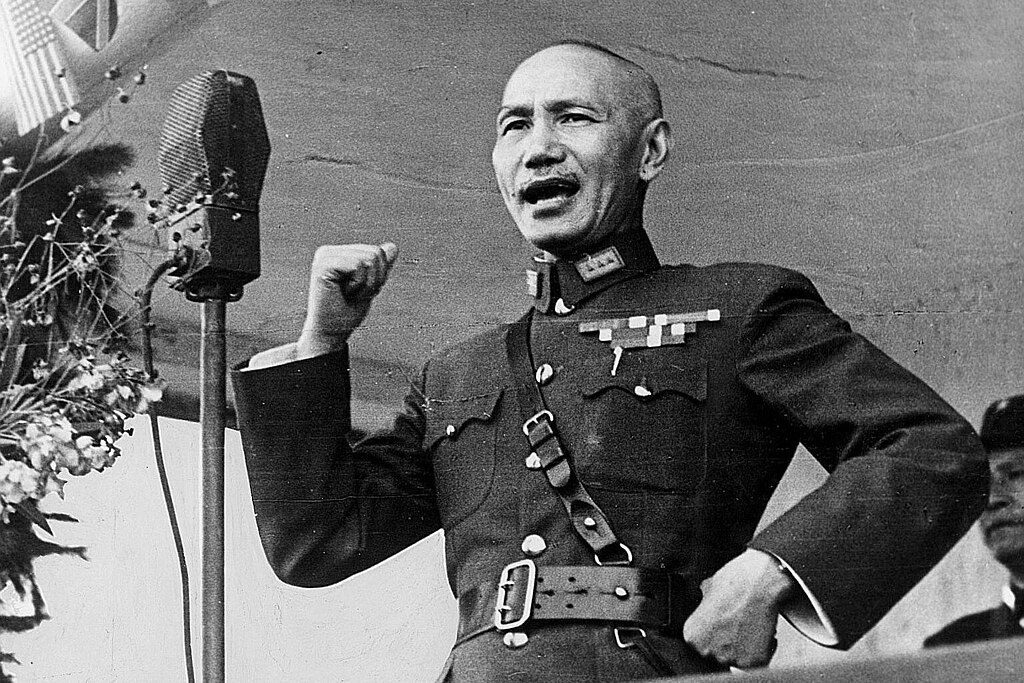

The story tells how in 1934, Mao, the wily general and masterful political theorist, guided a badly-led, starving, broken army away from certain destruction on a year-long, 6,000-mile odyssey across China’s hinterland to safe haven in the north. From there, the Red Army would rise anew, playing a crucial role in the struggle against the invading Empire of Japan before overthrowing the corrupt and ailing Kuomintang (KMT, or “Nationalist”) regime led by Chiang Kai-shek.

This story, told in this way, became so vital a bedrock of Communist rule in China that even today the ruling party retains an iron grip on its telling. And like many great myths, there is substantial truth beneath the story – but the whole truth is every bit as astonishing a tale of human resilience and historical luck as the propaganda.

THE FIRST CHINESE CIVIL WAR

It could be said that The Long March began not in October 1934, but instead in Shanghai in April 1927. That spring, Chiang Kai-shek turned on the Chinese Communist Party, his erstwhile allies, slaughtering 5,000 and forcing the remainder to flee to the countryside.

In 1931, the exiled remnants of the Party founded the Central Revolutionary Base Area, better known as the Jiangxi Soviet after the province in which it was located. Chiang, a fanatical anti-communist (a decade later, he would call them “a disease of the heart”) began a campaign of sieges against the Soviet immediately after its founding.

The Communists skilfully beat their opponents back during the first four “encirclement campaigns,” until Chiang finally played to his strengths and constructed roads and concrete blockhouses to box the lighter-weight Jiangxi forces in.

By the summer of 1934, while Communist leaders exhorted “our millions of worker and peasant masses [to] become an unbreakable armed force to fight along with our invincible Red Army,” the Party had already informed Moscow of its plans to flee and preserve the movement for another day. On 16th October 1934, the Long March, consisting of 130,000 soldiers belonging to the Communist 1st, 2nd, and 4th Armies, began; it was, said one survivor, “a state on the move.”

MAO ASCENDANT

The Chinese Red Army’s first priority was escape. Chiang’s army was larger, better-equipped, and determined. If the Communists were to survive, they first had to evade this powerful enemy.

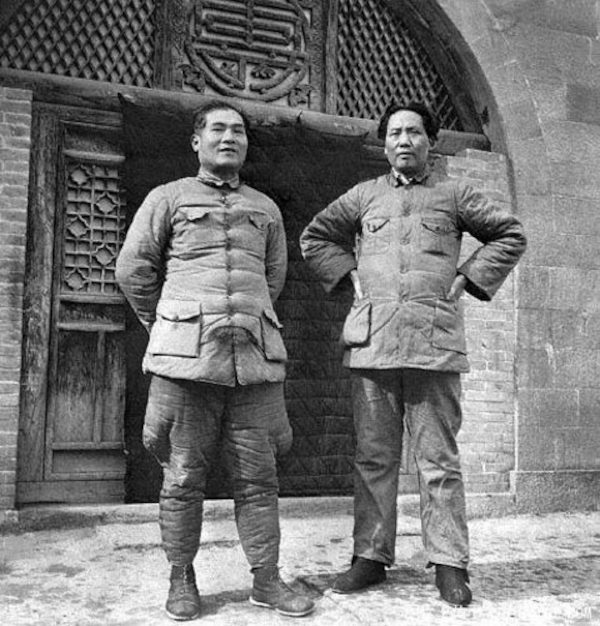

Although he was one of the founders of the Jiangxi Soviet, Mao’s political tactics and a series of vicious purges had cost him support. By the time the Long March began, he was at best a figurehead, behind Communist leader Bo Gu and Comintern agent Otto Braun. But once the 1st Red Army – already having lost 50,000 of its 86,000 soldiers to desertion and battle – had evaded Chiang’s blockhouses, he persuaded the army’s leaders, with support from Zhou Enlai, to overrule Bo Gu and Braun and head for Zunyi in Guizhou, central-southern China.

In the orthodox Communist narrative, it was here, in mid-January 1935, that Mao finally began his return to power. “Many would say in the future,” wrote the American journalist Harrison Salisbury, “that it was the single most significant event in the whole Chinese Revolution.”

At Zunyi, as the official story goes, Mao criticised the military errors of Braun and Bo Gu, gained a seat on the Secretariat of the Politburo – one of the highest bodies of the Party, then and now – and took control of the March. It was only many decades later that careful research revealed some holes in this story.

The writer Sun Shuyun, while traveling along the Red Army’s route to research her book on the Long March, learned that even after the March ended, “Zunyi was not even mentioned… until well after 1949.” He could not have taken power just at Zunyi, because many of the maneuvers and events that did propel him to power were yet to come. After all, the Long March had only been underway for three months when the Zunyi Conference took place; there was still almost a year to go.

ON THE MARCH

Beyond propaganda, there’s no question that the battered Red Army went through extreme hardships while pulling off astonishing feats of arms. They scored very few outright victories; instead, their major successes were in eluding Chiang’s forces through deception and incredible exertion.

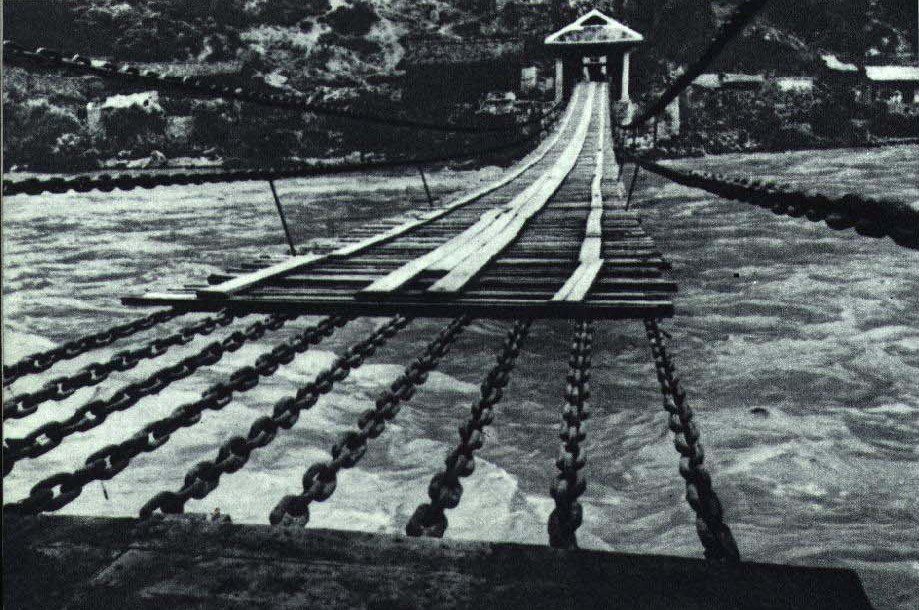

Along with the Zunyi Conference, perhaps the most storied moment of the March was the Battle of Luding Bridge. A suspension bridge built from massive iron chains in 1701, the Luding Bridge was at the time the only safe crossing over the Dadu River into Sichuan Province for hundreds of miles. If the 1st Red Army could get across, they could link up with Zhang Guotao’s 4th Red Army while the Nationalists would be forced to detour for weeks, even months, to catch up with them.

Chiang’s ally, the warlord Liu Wenhui, held the bridge and the town on the western bank. He had had his men tear up the planks covering the chains at one end and left a squad of soldiers to protect it. But the single squad of soldiers, equipped with poor-quality ammunition, couldn’t hold off the Communists, who crawled along the chains and allowed the rest of the army across.

When the 1st and 4th Red Armies finally reunited, Mao’s 1st Army was desperately in need of relief. Many had begun the March without even shoes – one man recalled “I never had a complete uniform until I finished the March!”

The reunion gave both armies – Mao’s by now whittled down to just 10,000 – renewed hope.

The two leaders, however, quickly clashed. Mao wanted to travel to a surviving Communist base in the northern province of Shaanxi, whereas Zhang wanted to establish a new one near the Russian border. In September 1936, Mao, his army now down to just 8,000 men after transferring some to the 4th Army, fled in the dead of night.

Zhang allowed the defectors to leave, and sent many of his troops west to carry out his plan. It was a disaster: the western provinces were home to Muslim Nationalist warlords who led some of the fiercest and most effective armies in China.

By the end of the year, 20,000 men and women, renamed the Western Legion, had been annihilated. The few survivors were killed or captured, and many of the women raped. Zhang himself, having lost the power struggle with Mao, would defect to the Nationalists in 1938 and die in exile in Ontario in 1979.

WHEN DID THE LONG MARCH END?

The shrunken 1st Army, meanwhile, had turned north through the swamps and grasslands of Tibet. Hunger and terrain were their greatest enemies: they stripped the grasslands of what few edible plants they could find, and they were even forced to eat belts, boots, and horses. Hundreds froze in their threadbare uniforms; many drowned in the treacherously deep mud and water off the roadside. When they finally made it out, many died a painful death from eating unripe corn.

When they finally sighted the town of Huining, Gansu Province, in October 1935, “We surged toward [it] like a flood breaking through a dam,” recalled Wang Quanyuan, commander of the 4th Army’s Women’s Regiment. But it was a bitter victory: less than 10% of the force which had left Jiangxi the year before had made it all the way.

Moreover, they weren’t out of danger yet – the Shaanxi base, led by Liu Zhidan, was too small and poor to support even Mao’s diminished Red Army. And Chiang was still menacing the surviving force, fully aware that he was close to wiping them out.

The Communists took a new tack: instead of fighting each other, they said, all Chinese armies should unite to drive out the Imperial Japanese Army, which had occupied Northeastern China and was preparing to launch an all-out attack. Realizing his advantage, Chiang refused until, in December 1936, Zhang Xueliang, a colorful warlord who sympathized with the Communists, took the outrageous step of simply kidnapping the Generalissimo in the Xi’an Incident.

Chiang was forced to accept the Communists as allies, and the two factions would maintain an uneasy, and purely formal, ceasefire until 1945. But in the end, the Communists had achieved their goal: the Red Army had survived.

THE MYTH

The story of the Long March began to take shape while it was still underway. From his youth, Mao had demonstrated a knack for propaganda, which would become infamous in later years. Propaganda teams collected stories from Long Marchers while they traveled, and as soon as they could stop to edit and print them, they produced a book-length collection of 100 testimonies which became the foundation for the Long March myth.

In reality, the Long March was a catastrophic defeat, depriving the Communists of their bases, resources, and much of their manpower. It was a stroke of genius on Mao’s part to turn it into a heroic epic. But as mythologized as large parts of the story were – “there wasn’t much to” the Battle of Luding Bridge, as Deng Xiaoping would later remark – it did contain a great deal of truth and some real successes, primarily for Mao.

Mao did not take complete control at Zunyi and did not skillfully or flawlessly guide the tattered Red Army to victory. In fact, most of the battles he directed after securing control of the army in 1935 were defeats. But he did end the March in control of the Party and with enough of an army left, and enough breathing room to rebuild it, to once again become a credible threat.

The Communists also received a welcome boost in 1936 when an American journalist, Edgar Snow, traveled to Shaanxi to tell their story. Bizarrely, the meeting was arranged by Soong Ching-ling, Chiang’s sister-in-law. Over several months, Snow interviewed ordinary Communist soldiers as well as leaders – he even conducted the only interview Mao ever gave about his early life – and, after it had been approved by Party leaders, turned the material into a book titled Red Star Over China.

In modern China, the story of the Long March is as fundamental a national epic as the Storming of the Bastille in France or the ANZAC myth in Australia. And it is because of books like Snow’s, and that produced by the Communists in 1938, and dozens of propagandistic and artistic accounts of the story over the last century, that the tale has held fast ever since, in China and beyond.

Perhaps the only real truth lies in the horrors and trials the Long Marchers endured. Without proper clothing; without enough food, medicine, ammunition, shelter, or sleep; without knowing where they were going, or whether they would survive from day to day; they endured a hellish journey for which many of its participants never received proper credit. Countless Long March veterans were tormented during the Cultural Revolution, and many never even received the pensions they were owed for playing a part in the creation of the People’s Republic.

Li Wenying, a Western Legion veteran, was one such victim of the Red Guards, who tortured and beat her in the 1960s. “So many times,” she later told Sun Shuyun, “I wanted to kill myself. Death was so tempting, so near. But I couldn’t bring myself to do it. After all I had been through, how could I die for nothing?”

Podcasts about the Long March

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 202

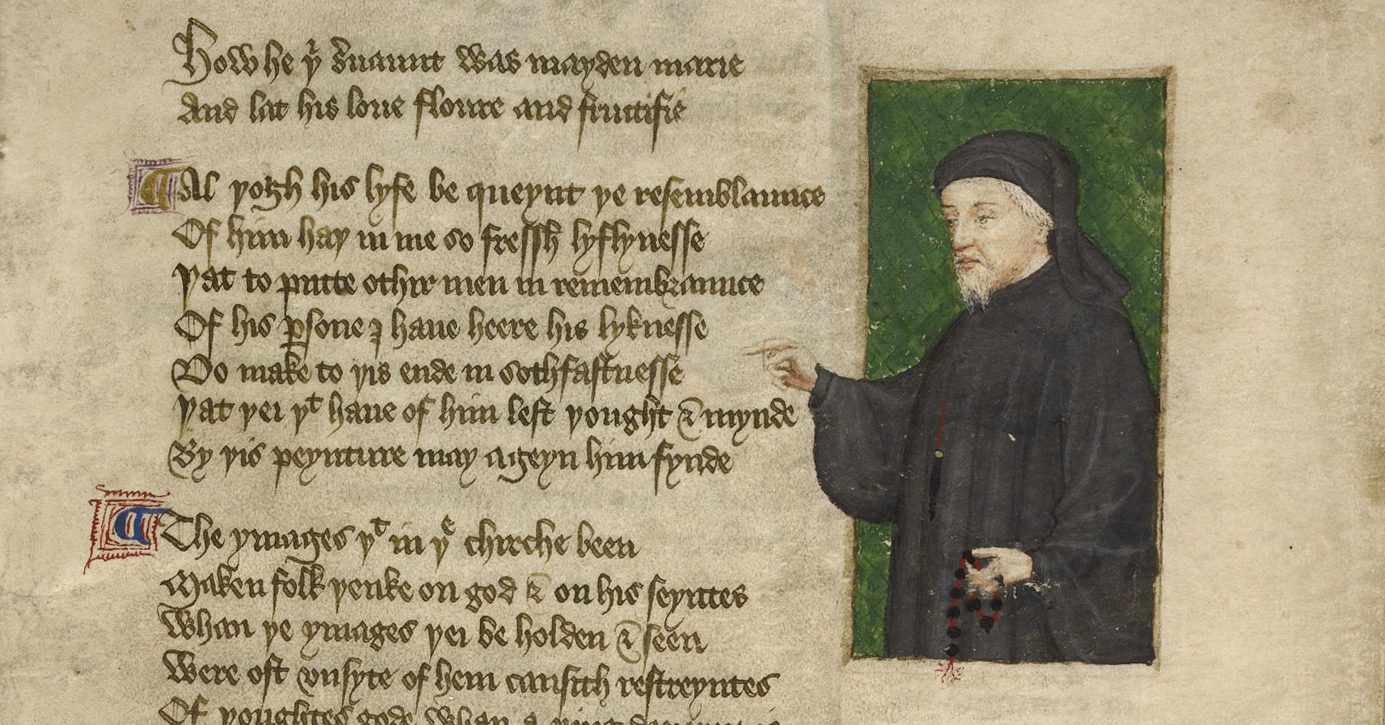

1. Writing in the 1380s, who was the first to refer to Valentines Day on the 14th of February?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

Home Made Wings – Australian Military Aircraft Manufacturing – Video

This documentary explores the history of Australian military aircraft manufacturing. Australia had just completed its industrialisation in 1939, becoming a full war economy very rapidly.

Menzies’ call on Vietnam changed Australia’s course

Reading time: 4 minutes

In 1965, Australia was involved in two crises in Southeast Asia, one in Vietnam and the other in Indonesia. The connection between the two was vital to Menzies’ decision to increase our involvement in Vietnam. Having already committed a battalion to Malaysia to support resistance to the Konfrontasi policy of Indonesia’s Sukarno government, the logical next step for Menzies was to look to Vietnam. He did this with the support of his Cold War warrior and minister for external affairs, Paul Hasluck. They decided to send an Australian battalion to South Vietnam, partly to ensure continued American interest in the region.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.