Reading time: 7 minutes

In December 1792, detachments of the 2nd Dragoon Guards across the Southwest of England staged spectacles of hate. A dummy was paraded through the towns on an ‘ass’ led by a hangman, the crowd of soldiers and residents encouraged to subject it to ‘every possible mark of indignity’.

By Andrew Coltart

At the customary place of execution, it was burned amidst repeated exclamations of ‘“God Save the King”, and constant cheering and huzzahring’. The dummy was an effigy, of the radical writer Thomas Paine.

Paine was no stranger to controversy – he had been a vocal supporter of the American Independence. By 1790, he had moved on to become the most prominent English advocate of the French Revolution.

A revolutionary riposte

The French Revolution began in 1789 as Louis XVI, facing a gigantic economic crisis, called an Estates General, an advisory assembly, to discuss solutions. The Estates General was made up of three separate Estates: The First comprised the aristocracy, the Second the clergy, and the Third represented all others, although its members were largely drawn from the professional middle classes. The Third Estate unilaterally created a National Assembly, a kind of parliament, and began demanding a constitutional monarchy. Monarchist counterrevolutionaries, with the support of European powers including Britain, resisted change, and plotted. In the Assembly and its successors, republicans gained ascendancy, and the French Republic was proclaimed in August 1792. The Republic declared the equality of rights and liberty, but it was threatened on all sides. On 17 January 1793 the former King, now Citizen Louis Capet, was executed.

The American Revolution had plenty of supporters in Britain’s elite, including Edmund Burke MP, now considered the founder of modern conservatism. But the French were a different, more radical quantity. Burke used his 1790 pamphlet, Reflections on the Revolution in France, to predict the Revolution would collapse into blood anarchy. He upheld Britain’s Parliamentary constitution, which excluded most of its workers from voting, as a bulwark against such tyranny that must be cherished.

Rights of Man, published in two parts in 1792, was Paine’s riposte to Burke. Britain’s constitution was out-of-date, ‘eclipsed by the enlarged orb of reason, and the luminous revolutions of America and France’. In the second part he laid out practical steps to renew it, including universal suffrage and the abolition of the monarchy. Such ideas were dangerous. The government bought copies of Rights of Man, prosecutors underlining offending passages.

Paine was not the only radical pamphleteer, but he was the most infamous. The Home Office’s correspondence was awash with alarmed reports of its distribution – it was sold cheaply, or given away gratis, sometimes even to troops. It was being translated into Welsh, as an ‘infestation’ of Methodist preachers extolled its doctrines. A bookseller holding a lucrative position as a tax-collector had sold 1,000 copies.

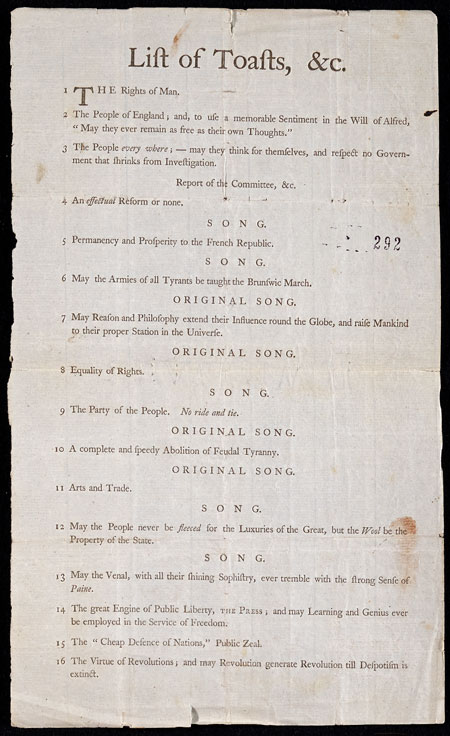

What’s more, this dissemination of literature seemed to be translating into wider radicalism. In December a list of toasts proposed at a dinner of the Reforming Society in Borough (Southwark, probably the Friends of the People) was sent to the Home Secretary. They included not just the ‘Rights of Man’, and ‘the People’, but also for the ‘Abolition of Feudal Tyranny’, and the ‘Virtues of Revolutions’.

Two days later it was reported that over 40,000 muskets had been sold in London. It was claimed that another reform group, the Society for Constitutional Information, had raised a subscription for a substantial portion of these, and that they might be storing them to arm a French invasion force. There was little hard evidence of such a scheme, but the atmosphere was febrile.

Sedition: cousin of treason

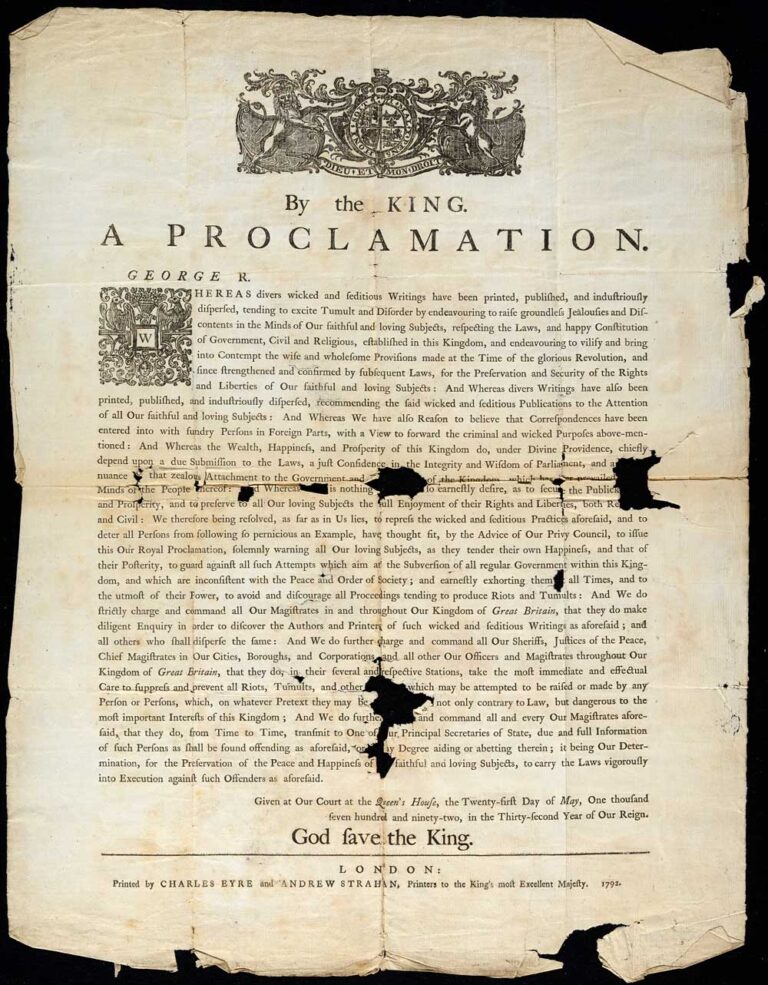

To try and quell the radical press, the government issued a Royal Proclamation on 22 May 1792 against ‘wicked and seditious Writings … endeavouring to vilify and bring into Contempt the wise and wholesome’ constitution.

Magistrates were charged with seeking out the authors and printers of such material, and reporting to government on radical activities. All subjects were instructed to, ‘guard against all such Attempts, which aim as the Subversion of all regular Government within this Kingdom’. Paine was not named, but he was implicitly the target.

It was not long before Paine was named by the government, his name on an indictment for seditious libel. Sedition was the close, junior cousin of treason, characterised by the jurist Francis Holt as an ‘endeavour to despoil’ the state of the ‘affection of its people’, but not going as far as attempting to overthrow it. The Attorney General, prosecuting, explained to the jury that Paine had written Rights of Man intent on making ‘the lower orders of society disaffected to Government’.

The trial, at the Court of the Kings Bench, began on 18 December 1792. Paine was defended by Thomas Erskine, perhaps the greatest lawyer of his generation. Erskine used his defence speech to argue for freedom of press and expression. He described the proceedings as little more than a show-trial. Proving his point, the jury informed the court there was no need for the prosecution to make a counterargument – they were already convinced of Paine’s guilt. The government and loyalist vilification of him was working.

Paine was convicted in absentia – he was in France at the time, where he had been elected a member of the revolutionary National Convention. But, Paine’s conviction allowed the government to say that his ideas, and those of radicalism, were a threat to the stability of the constitution, and therefore the Crown. When the reformers of the London Corresponding Society were tried for High Treason in 1794, it is no coincidence that large chunks of Rights of Man, which they had promoted, were read out as prosecution evidence.

The treason trials failed, not least because of Thomas Erskine, who again led the defence. But Paine was firmly cemented as a loyalist folk-devil, he – and his ideas – seditious, dangerous, even treasonous, soaked in the blood of the French Revolution.

Paine never returned to Britain, returning to America, where he held citizenship, in 1802. He continued to write prolifically on American, French and British politics, but his health failed, and he died in 1809. Such was his legacy and influence, though, his writings remained central to later radicals. His supposed villainy, slovenly habits and excessive drinking continued to be attacked by loyalists.

Paine was never charged with treason in Britain. Indeed, the closest he came to a traitor’s death was at the hands of the Terror’s Committee of Public Safety, who imprisoned him in December 1793. But to many British people, he was a traitor nonetheless. Treason is emotional as much as it is legal. Paine’s conviction for seditious libel laid the ground for the trials of peaceful radicals and set the stage for decades in which parliamentary reformers were ever on the precipice of accusations of treason.

This article was originally published in The National Archives.

Podcasts about Thomas Paine:

Articles you may also like:

X Troop – The Secret Jewish Commandos of WWII

Reading time: 8 minutes

When we hear ‘Jewish’ and ‘World War II’ in the same sentence, our minds often lead directly to the Holocaust. The extent of Jewish resistance to the brutal treatment on their own was limited due to the extent of their persecution by Nazi or Nazi aligned governments. These governments generally had the broad support of the populace, making it hard for small groups of Jews within these societies to fight back. One exception to this were the Jews of Poland, the X Troop commandos were another.

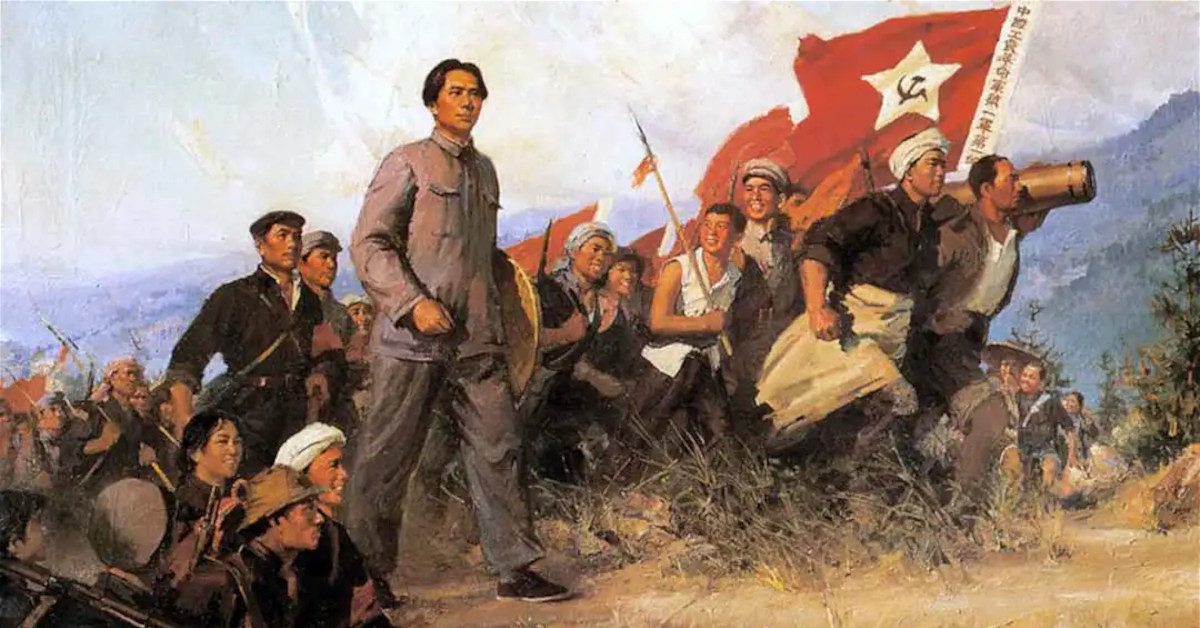

THE 25,000-LI JOURNEY: INSIDE THE LONG MARCH, MODERN CHINA’S FOUNDING MYTH

Reading time: 12 minutes

On 21th September 1949, Mao Zedong took to the podium in Huairen Hall, Zhongnanhai, a former royal residence in Beijing, to announce that “the Chinese people, comprising one quarter of humanity, have now stood up.”

These striking words were all too appropriate for the moment: for Mao it represented the end of a quarter-century journey to the pinnacle of his own party and finally his country – a journey which began with the Long March.

This article was first published by The National Archives. It is reproduced in accordance with the Open Government Licence v3.0.