Reading time: 4 minutes

December 6 is celebrated by the Christian churches as the feast day of St Nicholas. The saint is one of the historic figures on whom Santa Claus is based and so today is the closest the world gets to a Santa Claus Day.

Nicholas was the Bishop of Myra in the early fourth century at the time when Christianity entering into full flight under the Emperor Constantine as the imperial religion of the Roman Empire. Legends reveal him as a secret giver of gifts to the needy, whose charity was saintly because it brought no honour to the giver, only help to the recipient. His gift-giving is thus one of the Christian antecendents of the practice of disguising Christmas presents in stockings or wrappings.

By Peter Sherlock, University of Divinity

St Nicholas Day should be on the list of answers to the difficult question, when’s the right time for us to put up the Christmas decorations?

If you’re a Scrooge like me you’re probably already sick of the Christmas decorations that have been invading public spaces in our cities and towns and neighbourhoods for the past month. At least North Americans wait till after Thanksgiving, and the British till after Remembrance Day.

For western Christians, a strong candidate is the first Sunday of Advent. This is the Sunday four weeks before Christmas Day, that marks the Christian New Year, a period of anticipation of the second coming of Christ.

Purists might stick with the December 25 itself. Children might want every one of the 12 days of Christmas, that run from the 25 December to the 6 January.

And for eastern Christians, the main event is January 6 itself, when the church celebrates the coming of the sages from the east to visit the Christ-child in his cradle at Bethlehem. For this moment symbolises the Christian truth that through Jesus, God offers salvation to all people, making a new promise in addition to the divine covenant with the Jewish people.

Non-believers will rightly point out that the Christians borrowed the dates of Christmas from the pagans in the first place, so it doesn’t really matter.

Historians might opt for January 1 and the medieval practice of the New Year’s Gift.

Personally, I reckon today – St Nicholas Day – is a good candidate for putting up the decorations and setting out the presents.

As Bishop of Myra the ancient saint was one of the strongest opponents of the Arian heresy that threatened to dilute the recognition that Jesus Christ was fully human and fully divine. This doctrine was captured in the Nicene Creed, a statement of belief to which Nicholas subscribed at the famous Council of Nicaea in 325. He is said to have struck Arius during the Council, for which act he was temporarily expelled. As a defender of orthodoxy, a true believer, his day is a good pick for the purists like me.

But St Nicholas was also a wonder-worker. He is the patron saint, amongst other occupations, of thieves, pawnbrokers, and merchants. As such he’s a good fit for the true spirit of Christmas in our 21st-century world.

For the most powerful religion in our present time is capitalism. Christmas is the climax of our capitalist religious year when Santa Claus might spare us from the poverty of our neighbours. Commentators and politicians reinforce our hope that retail sales during our great festival will be strong enough this Christmas to stave off an economic famine for the next twelve months.

Even our relationships with families and friends are subjected to an economy that relies not on the wonder of the gift freely given, but on carefully calibrated exchanges.

We could use a wonder-worker, a true believer, and a secret giver of gifts.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about St Nicholas

Articles you may also like:

The Siege of Malta through Australian eyes

Reading time: 11 minutes

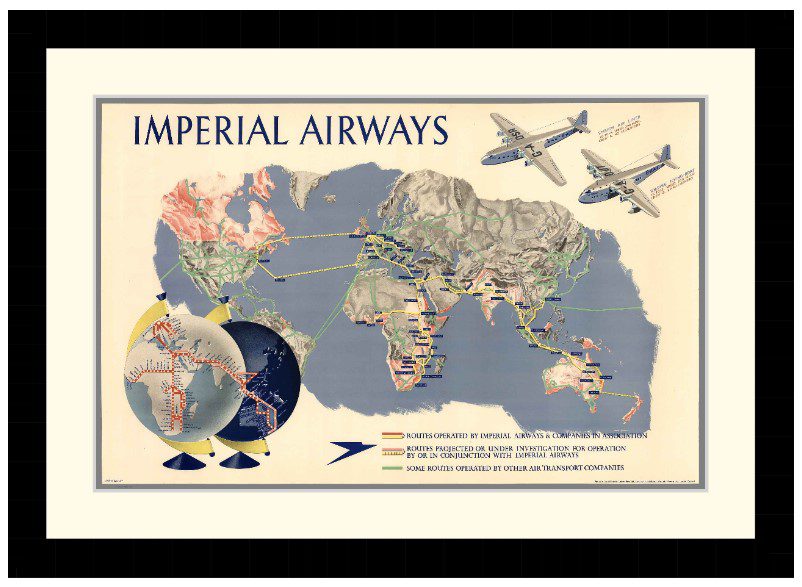

The Siege of Malta in the Second World War, which lasted from June 1940 until November 1942, was a linchpin of the war. Had Malta fallen to the Axis, the war may have concluded very differently. Australian soldiers, sailors, and airmen played a crucial part in defending the island, in this article we explore how they experienced it.

The Empresses of Constantinople – Audiobook

THE EMPRESSES OF CONSTANTINOPLE – AUDIOBOOK By Joseph Martin McCabe (1867 – 1955) In concluding an earlier volume on the mistresses of the western Roman Empire I observed that, as the gallery of fair and frail ladies closed, we stood at the door of “the long, quaint gallery of the Byzantine Empresses.” It seemed natural and […]

History and myth: why the Treaty of Waitangi remains such a ‘bloody difficult subject’

Reading time: 10 minutes

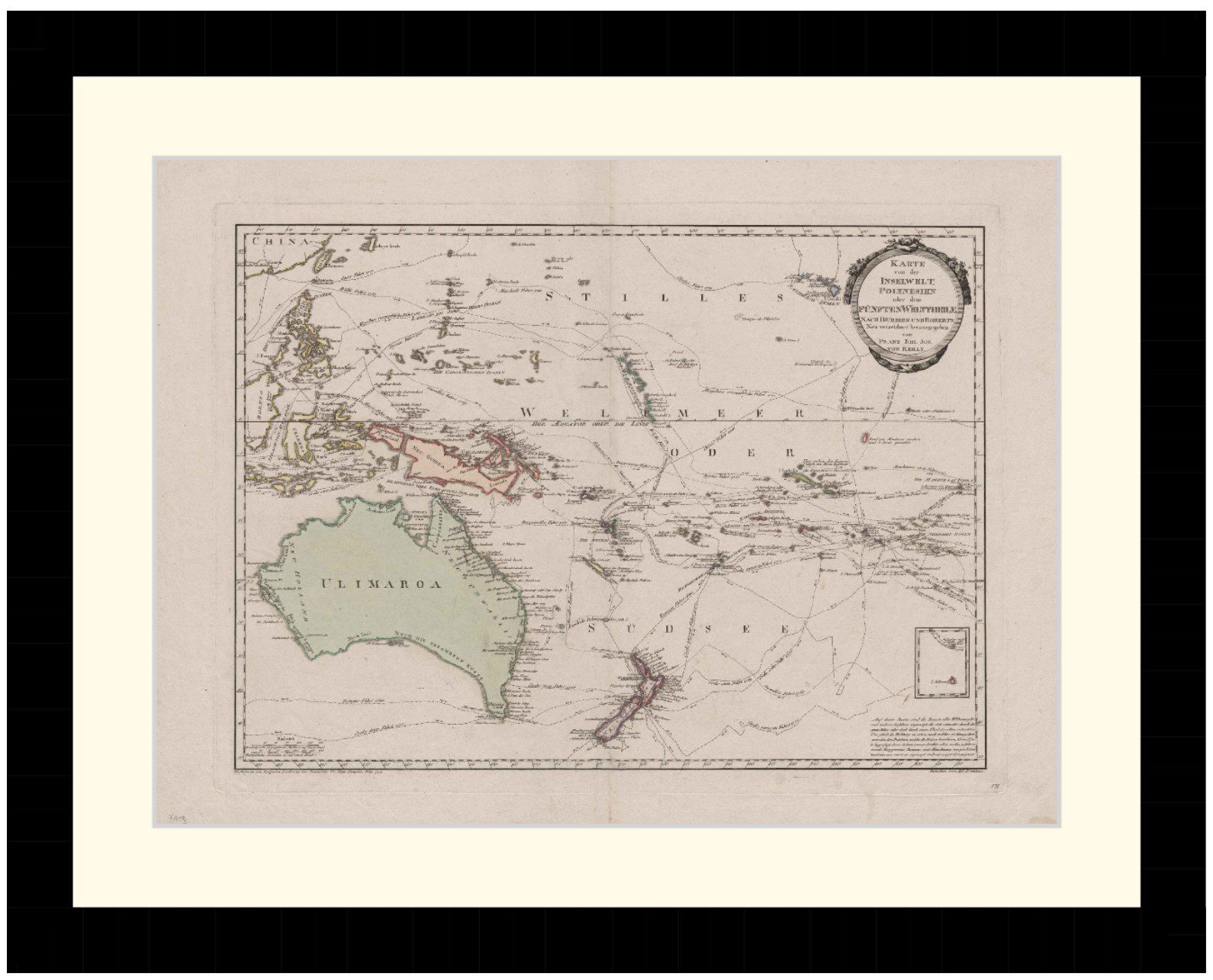

The Treaty of Waitangi, the influential historian Ruth Ross (1920-1982) remarked in 1972, is “a bloody difficult subject”. She should have known – she devoted most of her working life to trying to make sense of it, especially the text in te reo Māori. That difficulty persists to this day.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.