Established on October 18th, 1939 in Melbourne, as a part of the 17th Brigade of the 6th Division. Its creation was in response to the outbreak of World War II, with the Australian government deciding to raise an all-volunteer force given that the Defence Act did not allow part-time military forces to serve overseas. The battalion’s initial core comprised many recruits from the Victorian Scottish Regiment, a militia unit tied historically to the 5th Battalion from World War I. The unit initially assembled at the Royal Melbourne Showgrounds and later moved to the newly-established military camp at Puckapunyal on November 2nd, where they underwent basic training before deployment.

On April 14th, 1940, the battalion left Australia, embarking from Port Melbourne on the HMT Ettrick, destined for the Middle East. They arrived in Egypt on May 18th, 1940, and underwent further training in Palestine and Egypt. The 2/5th first saw action in the North African campaign, notably participating in the advance against Italian forces in eastern Libya. They were involved in the successful attacks on Bardia and Tobruk in January 1941, which were significant early victories for the Allies in North Africa. These battles saw the battalion suffer their first significant casualties, but established its effectiveness in combat.

In the spring of 1941, the battalion was deployed to Greece as part of the 6th Division to counter the anticipated German invasion. This campaign saw a series of strategic withdrawals, starting from defensive positions at Kalabaka and culminating in a retreat to Kalamata, from where they were evacuated by April 27th, 1941. Elements of the battalion fought at the battle of Pinios Gorge. During the evacuation, a contingent of 47 transport drivers was left behind and captured.

74 men of the battalion were inadvertently landed on Crete, where they formed part of 17th Brigade Composite Battalion, fighting in the Suda Bat sector. Many were taken prisoner.

Following these engagements, the 2/5th returned to Palestine but were soon called upon to participate in the Syria-Lebanon campaign against the Vichy French forces in June and July 1941. They played a crucial role in the Battle of Damour, which effectively sealed the defeat of the Vichy French in the region. After this success, the battalion remained in Syria and Lebanon as part of the Allied garrison forces, maintaining stability and securing the area until January 1942.

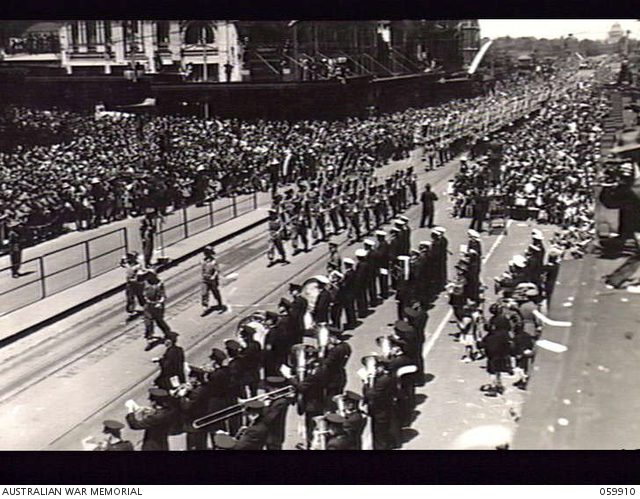

With the escalation of the Pacific War following the entry of Japan, the battalion was recalled to Australia in March 1942. However, en route, they were diverted to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) due to fears of a Japanese attack. They stayed there from early March until July, helping to fortify the island’s defenses. Ultimately, the battalion disembarked in Melbourne on August 4, 1942, after which they received a brief period of leave.

The battalion was then sent to New Guinea in October 1942, initially to Milne Bay, and later played a significant role in the fighting at Wau in January 1943. This involvement marked the beginning of continuous operations against Japanese forces in the Pacific, including intense engagements around Goodview Junction and Mount Tambu during the Salamaua campaign in mid-1943. These battles were part of broader efforts to weaken Japanese positions ahead of Allied offensives in the region.

Returning to Australia in September 1943, the 2/5th spent the following year in northern Queensland, undergoing training and reorganisation to prepare for further operations. Their final campaign commenced in late November 1944 when they disembarked at Aitape, New Guinea. For the next several months, they engaged in arduous patrolling operations through the Torricelli and Prince Alexander mountain ranges, aimed at clearing the remaining Japanese resistance. This phase of their service was marked by difficult jungle warfare, which resulted in significant casualties but helped cement the Allied victory in the Pacific.

With the war’s end in August 1945, the battalion returned to Australia in December 1945. They were disbanded at Puckapunyal in early February 1946, marking the end of their distinguished service. Throughout its operational history, the 2/5th Battalion engaged in significant battles across three continents, fighting against all of Australia’s major wartime enemies—Germany, Italy, Japan and Vichy France, a unique honour they share only with the 2/3rd Battalion.

Throughout the war a total of 2,967 men served with the 2/5th Battalion, of whom 216 were killed, and 390 wounded. Members of the battalion received two Distinguished Service Orders, 14 Military Crosses, six Distinguished Conduct Medals, 20 Military Medals, and 56 Mentions in Despatches. One member of the battalion was appointed as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire and three were appointed Members of the Order of the British Empire. The battalions’ battle honours were inherited by the 5th/6th Battalion, Royal Victoria Regiment, an Australian Army Reserve battalion.

MEN OF THE 2/5TH AUSTRALIAN INFANTRY BATTALION

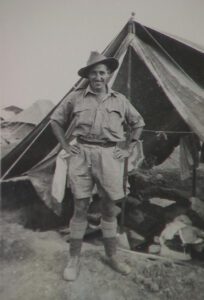

Staff Sergeant William ‘Bill or Dunny’ Gilbert

20-year-old William “Bill” Gilbert was drinking tea with his parents when he heard over the radio that Australia was at war. The very next day, he enlisted in the AIF, something both his parents and his girlfriend were very proud of. Unbeknownst to Bill, his father did the same, and would eventually come out of the war as a sergeant. 15 months later Bill was in the Middle East, fighting his first battle as part of the 2/5th Australian Infantry Battalion at Bardia.

“Tim Seymour, he was my good mate, and a lovely young lieutenant was killed. A bullet went through his steel helmet. Straight through there (indicates the middle of the forehead). I was alongside him when it happened. Buster Simmington was a friend of Tim’s. They were in World War I together, and he was a sergeant. He got a terrible wound to his head, and he dragged himself from here to our back door and lay in front of a couple of the boys who survived and said ‘Here, use me as protection.’ He died there, and after what they’d been through in World War I, he copped it so soon in World War II.” – Bill remembered.

After Bardia came the Battle of Tobruk, where the 6th Division, of which Bill was a part, was relieved by the 7th Division. After a four-day leave in Alexandria, the entire division was shipped to Greece. Bill had a bad feeling from the get-go, as when they arrived in Athens, they could see a British hospital ship destroyed by German bombing. That bombers could get so deep into allied territory told him that there was little opposition. ANZAC troops were then taken by train to Camp Daphni, “a strange name for Greece and definitely a camp,” as Bill noted. About a week later, it was time to move towards the Greek-Yugoslav border, again on a train:

“We had biscuits from World War I, and we were sitting in the cattle truck breaking them up with our rifles, and there was an air raid, of which there were many, and the Greek fireman and the driver, they’d take off across the fields. One of us had to go up to the engine, get some hot water out of the engine, and come back and put it amongst our biscuits to soften them up. It took us about 2 days to get up there because every time there was an air raid, they just took off, and it might be half an hour or more before they’d come back once the planes had gone.”

It took Bill and his unit more time than planned to reach the front, and by the time they made it to Larisa, Germans had already breached the Greek border:

“We got on top of the Thermopylae Pass, I think it was, and it was very high. You could look right down across the flats, and you could see hordes of German Infantry coming across the flats, and one of our artillery units fired some shells over towards them, but it was too high. But the Germans were so good at working things out, in no time flat they had the correct range, and they got right onto our artillery, and we didn’t actually have any hand-to-hand fighting because – at the very end of it we did, but they were just putting us down that quickly we had no time to do anything, and we were constantly bombed because there was no opposition.”

Bill and what was left of his unit had German pursuers some half a mile away at the time they reached Kalamata, where they boarded a navy destroyer which pulled up alongside a little wooden wharf alongside the road. It took them to the City of London, the same troop ship that would 12 months later bring Bill home to Australia. This time, however, it took him back to Palestine. He received a four-day leave, but he went AWOL for one additional day to finish a tennis tournament he had started in Tel Aviv.

Looking back at the campaign in Greece, Bill was most struck by the lack of air support, which he found instrumental in the German victory on the peninsula: “In Greece, we only saw 3 Allied planes in the air, and I saw the 3 of them shot down. The Germans just bombed us all the time. They had no opposition. Only guns from the ground like ack [anti-aircraft] guns and things like that.”

Having done his share of fighting, Bill transferred from the 6th to the 9th Division and dealt with support and supplies. In 1942, while heading to Sumatra, naval engagements prevented them from reaching their destination, and they temporarily diverted to Perth. This is where Bill proposed to his soon-to-be wife and managed to get married before heading to New Guinea where he stayed to the end of the war. He was a staff sergeant at discharge.

Looking back at the overall experience of the war, Bill concluded: “I had become a man. I could take things and I could give things if I had to, and I didn’t appreciate the fact that people had to be killed for war, and I’m not very interested in wars for that reason. You’ll find that there are lots of people that benefit greatly from the war while others are losing their lives. It’s a bit of a sore point. I know several blokes who made fortunes during the war without even enlisting, and that was a bit of a sore point with me. I reckon one in, all in if you’re fighting and if Australia’s involved in it, I reckon we should all be in it or not at all.”

Private Ivor White

Ivor White fought in the Greek, Syrian, and Papuan campaigns. When it was declared that Australia was at war, Ivor remembered feeling excited, but the idea of joining up never crossed his mind. However, after Dunkirk and the unrelenting German attacks on Britain, Ivor reconsidered and decided he wanted to contribute to the war effort.

He put his age up by two years, enlisted in the AIF and was sent as a reinforcement to the 2/5th battalion. “I can tell you the originals, they were very proud and we were reinforcements, and don’t you worry they let you know, if you were a bit late in joining up, and they would let you know,” Ivor remembered. In any case, on the 9th of April 1941, he sailed for Greece:

“When we got to Greece, we saw sunken ships and that sort of thing, but it didn’t sort of mean much. When we got there, and I was in Greece for twenty-one days and I never slept in the same place for two consecutive days. I remember going up and we could see the poor old Greeks coming back, they had one leg or one arm missing like that, and I said ‘This is bloody beautiful.’ and we are going up to where these poor bastards have come from. We went up, and I don’t think we struck the planes until we were coming back, I don’t think so, you might as well say we had a sort of uneventful time, so we got up as far as the Yugoslavian border.”

No sooner did the reinforcements for the 2/5th Battalion arrive than the campaign turned to retreat. The troops were transported 25-30 to a truck, but when German aircraft struck, they would abandon their vehicles, run some 500 yards away, and dig in until the attacks passed. Ivor saw quite a few people get wounded but did not see anyone die in Greece, although it would later turn out that his group had lost about 30 men. The retreat ended in Kalamata: “This was the time when I had won the Greek Gift [a race], fastest man in the 2/5th Battalion, I was the fastest man running and I was the first man on the Defender and I climbed up on the Defender (…) Sure enough, the dear old Defender popped alongside the City of London on the left-hand side, and Private White was the first one up.”

Despite a few near-misses, Ivor was lucky the City of London was neither hit nor did it stop by Crete on the way to Alexandria. Back in the Middle East, he met his brother who was in the postal service and offered to claim him; however, Ivor refused to leave his mates. “About two months or three months later when in Syria we were getting bombed, I remember lying there saying ‘You stupid bastard, why didn’t you go with your brother?’” Ivor remembered.

After Syria Ivor had served in the Papuan campaign and was discharged from the service in 1946. After the war he got married and fathered four children.

Podcasts about Australians in the Mediterranean during WWII

Did my Relative Serve in these Battles?

Hundreds of thousands of Australians served in the Mediterranean during the Second World War. Some families know what their relative experienced during this often very important part of their life, but many do not. History Guild has a project where our volunteers research the service history of Australians who served in the Mediterranean. We have had a lot of interest in this service and have a large backlog of research to get through, so it currently closed to new entries.

We hope to re-open this service once we have finished our research on the current set of Australian servicemen and servicewomen.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.