Formed in October 1939 the 2/2nd Battalion became part of the 16th Brigade, 6th Division, part of the all-volunteer Second Australian Imperial Force (AIF). The battalion adopted the same colors for its unit color patch as the 2nd Battalion, a unit with World War I service, choosing purple over green in a horizontal rectangular shape, with a grey border added to distinguish it from its Militia counterpart. Its motto was Nulli Secundus (Second to None).

With an authorized strength of around 900 personnel, the battalion, like other Australian infantry battalions at the time, was organised around four rifle companies (designated ‘A’ through ‘D’), each consisting of three platoons. Raised at Victoria Barracks, Sydney, the battalion moved to Ingleburn Army Camp for basic training almost immediately. In early 1940, the battalion was deployed to the Middle East, arriving in Egypt in mid-February and completing training in Palestine.

In January 1941, the 2/2nd participated in the Battle of Bardia and later contributed to the Capture of Tobruk. March 1941 saw the 6th Division sent to Greece, ahead of the expected German invasion. The battalion engaged in a critical delaying action at Tempe Gorge, also known as Pinios Gorge. Following the campaign, most of the battalion was evacuated to Palestine, but around 200 members participated in the Battle of Crete in May 1941. After the fighting on Crete, the 2/2nd was rebuilt and sent to Syria, where it undertook garrison duties from October 1941 to January 1942. The Australian Government requested its return following Japan’s entry into the war.

On the way back to Australia, the 2/2nd Battalion, along with the rest of the 16th and 17th Brigades, was diverted to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) to defend against a potential Japanese invasion. After successfully fulfilling this role until July, the battalion continued its return journey, arriving in Australia in August 1942. The following month, the 2/2nd participated in the Kokoda Track campaign, arriving as the tide turned in the Allies’ favor. The battalion fought several actions along the track, including significant ones at Templeton’s Crossing and Oivi. Heavy casualties were suffered as they counter-attacked and advanced north towards the Japanese beachheads around Buna and Gona. By December 1942, the battalion’s effective strength had fallen below 100.

The battalion was later withdrawn to Australia and, throughout 1943–44, was rebuilt and reorganized on the Atherton Tablelands in Queensland. After over a year of preparation, they were committed to the Aitape–Wewak campaign in late 1944, a mopping-up operation to clear the Japanese from around the airfield at Aitape and its surroundings. The campaign saw the Australians advance along the coast towards Wewak and inland towards the Torricelli Mountains. Lieutenant Albert Chowne, one of the battalion’s officers, was posthumously awarded a Victoria Cross for his actions during the campaign. members of the battalion received the following awards: four Distinguished Service Orders, nine Military Crosses and one Bar, four Distinguished Conduct Medals, 24 Military Medals, and 79 Mentions in Despatches. Throughout the war, 2,851 men served with the battalion, with 217 killed and 368 wounded. The battalion was disbanded on February 18, 1946, upon its return to Australia after the hostilities concluded.

The Men of the 2/2nd Australian Infantry Battalion

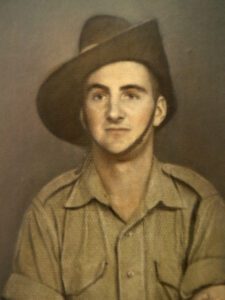

Private Albert “Jack” Ulrick

Albert Ulrick was born in 1918 in Maclean, NSW. In 1936, he joined the militia, an experience he did not find particularly helpful during the war, but which, nonetheless, made the transition into the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) smoother than that of the fresh recruits. When the war broke out, Albert was among the 16 members of his militia unit from Ulmarra who volunteered for the AIF.

“I remember this bloke, this McMahon rooster, he said. ‘Hey,’ he said, ‘what are you joining the AIF for? You know you’ll be sent overseas if you do that.’ One of the blokes behind me said, ‘For Christ’s sake, isn’t that where the war is?’”

In the Middle East, Albert contributed to the great Australian-led victory in Bardia. He participated in the siege of Tobruk, but victory celebration eluded him this time as Albert and his unit were among those pulled out and shipped to Greece: “We only got the one air raid on the way over. We landed at Piraeus and somebody told me after that the German ambassador to Greece was on the wharf watching us arrive. Germany and Greece weren’t at war then. Only Greece and Italy.”

Albert remembered that all the ANZAC forces were in high spirits from the victories over Italian forces, which he expected to face again in Greece, as they were attacking the country from Albania. Albert described the situation: “The Greeks were handling the Italians. Bloody schoolkids could handle them. But the Germans were a different kettle of fish. They were cocky, as you can imagine. They just conquered the whole of Europe and they hadn’t been silly enough to go into Russia yet, but they’d beaten Europe and they were coming in and they were flogging the Greeks.”

2/2nd Australian Infantry Battalion, along with other ANZAC forces, moved from Athens to Larissa. Albert remembers Greeks throwing flowers at them as they went north. The furthest he and his mates got was the Pinios River, where they tried to prevent Germans from crossing into Greece on 18th April 1941. The Battle of Pinios Gorge, also known as the Battle of Tempe Gorge, had ANZAC forces facing a force both numerically and technologically superior to their own.

Albert described the situation: “We knew what to expect. It wasn’t good enough. We were landed in Greece, didn’t even have our own artillery. We had New Zealand artillery, we had no aircraft, no heavy tanks. We had Bren gun carriers and a few parts of the armored brigade or whatever they called them. Nothing new. We didn’t have proper gear. Nothing.” To make things worse, his unit had not time to make any defensive preparations or use the terrain; it was straight into the fray.

After some time, Albert’s unit was in retreat, but he was not actually aware of this at the time. He remembered it simply as an order to move in another direction, and having little to no idea where they were going most of the time, this direction seemed as good as any. His detachment was composed of three carriers, which very soon got the attention of German mortars.

“So they started throwing three-inch mortars. And they’re pretty good those Jerries, with mortars. I reckon they could lob it in a bloody bucket; they were that good. It wasn’t long before we left the carriers in that hollow, we went over and into the next hollow, because they were drawing the crabs these carriers. They seen us do that too, I reckon. Next thing one landed in the hollow with us. It lobbed on the back face. Not far enough, and it all come back, this mortar shell. Three of us got wounded. The three drivers that were there. The other two blokes, I remember them rolling around squealing, yelling, ‘It’s burning!’ Because shrapnel is red hot.”

Albert was seriously wounded, shrapnel going through his chest, lungs, and sternum. He remembered thinking he was dead, only to wake up on the deck of another carrier. He had been saved by its crew. His childhood friend and schoolmate, with whom he shared a foxhole in Bardia, did not survive this attack.

After a couple of days of pursuit and heavy air raids, Albert’s mates managed to evacuate him to a British hospital near Athens. Here he met Sister Bathgate, who was also from Maclean and knew his mother and grandfather. “I remember her saying to the nurses and sisters, ‘This one is special. Don’t you let anything happen to him.’” Eventually, nurses were evacuated but all the doctors and orderlies remained in the hospital with men not well enough to travel. Albert’s brother, serving in a different unit, was also evacuated and fought for the rest of the war.

“The orderly came in one day; he was a funny old fellow. He said, ‘Do you know something?’ I said, ‘What?’ He said, ‘You’re now a prisoner of war.’ I said, ‘Fancy that.’ I burst out laughing. He said, ‘Hang on.’ So he lifted up the flap of the tent and said, ‘Look.’ And here was a Jerry in uniform with the rifle at the sling, walking up and down. I said, ‘Oh well, so be it. Not much we can do about it.’ He said, ‘That’s a bloody fact.’” – Albert remembered.

He remained in the hospital for the next six months and remembers seeing hundreds of wounded New Zealanders brought from Crete, many of whom eventually escaped. He did not remember ever being mistreated by Germans, not in Greece nor the working camps in Germany, where he spent the rest of the war in Europe. Nonetheless, captivity was an ordeal enough of its own. Eventually, he was liberated by American troops, and after a few weeks of leave in Britain, he returned home to his family. Albert got married in 1946 to Gwen, a girl he knew before the war.

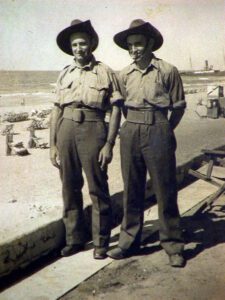

Sergeant Raymond ‘Jimmy’ Coombes

Raymond “Jimmy” Coombes was born in Forbes on the upper Hastings as the fourth son of a family of six boys. The first time Jimmy was shot at was when he was just 15 years old. His brother accidentally shot him with a .22 rifle. “The bullet went in my nose there and across my mouth, and the lead is still there in my neck.” While this led to a fear of firearms, it didn’t prevent Jimmy from enlisting on New Year’s Day 1940, when he was just 17. He was almost rejected based on his age and the fact that he put on the paperwork that he was 20. After some persuasion, “I got my regimental number and took the oath on the Bible, and I was in the army, and I enjoyed every day of my army career”, Jimmy recalled.

Jimmy remembered arriving in Greece via a ship before that country entered the war. His division found itself spread thinly in northern Greece along the border with Yugoslavia, anticipating a German attack. Jimmy explained that three passes led into the county, the coastal one held by New Zealanders (along the Albanian border), and two mountainous passes (towards Yugoslavia and Bulgaria) held by Australian brigades. Members of his unit had to carry their equipment up the mountains on donkeys to destroy bridges and roads leading into Greece.

Yugoslavia surrendered to Germany on the 17th of April, and the very next day, Jimmy and his unit faced the Wehrmacht along the Pinios River. What followed, we know today as the Battle of Tempe Gorge, also known as the Battle of Pinios Gorge. Here, despite staunch resistance, the Anzac forces endured significant losses and were compelled to retreat from the gorge. However, their resilient stand enabled other Allied forces to safely withdraw through Larissa.

“I think that was the closest we ever were because they had us in their sights with a machine gun,” Jimmy remembered telling one of his friends as they were retreating. He recalled exchanging fire with the enemy, but the 2/2nd Battalion eventually disintegrated under overwhelming pressure. With a few of his mates, Jimmy was directing the troops retreating through the passes until the point a superior showed up to warn them: “You’d better get on this carrier because… there’s no one out there, only Germans, so you’d better get on this carrier and come back with us.” In other words, Jimmy was among the last Australian soldiers to pull back from the Pinios Gorge area.

Jimmy described losing some of his mates during the chaotic retreat: “Bluey Dunn survived after the tank even ran over him, took the skin off him, and he got killed. Ken Cameron was taken prisoner of war, his legs were run over, his legs, and he had to get help and he eventually had to give in, and the Germans got him, and he finished the war in Germany.”

On foot, with carriers and New Zealand trucks, Jimmy and what remained of his unit eventually reached Kalamata. During the night, they were put onto a destroyer HMS Hero. The flotilla of destroyers, commanded by Lord Louis Mountbatten, encountered a squadron of some 30 low-flying German aircraft, as Jimmy recalled. He remembered a bomb hitting HMS Costa Rica, which resulted in her letting in water. Another destroyer pulled along the sinking vessel and transferred its crew and passengers onboard. Jimmy remembered seeing that three or four of the Stukas were shot down by the flotilla.

He assumed many of the troops from the flotilla ended up in Crete, as this was all happening near the island. However, Jimmy himself had more luck and ended up in Alexandria. Jimmy summed up his opinion of the Greek campaign: “Churchill promised the Greek government support, and we were sacrificed. We were a division of 10,000 troops that were sacrificed for something that we never, ever had a chance of doing any good. We lost all our equipment, guns, trucks, men. In our battalion, there were 178, I think, were taken prisoner of war, some killed, and we come back, luckily a few of us got out, a depleted battalion, well, a depleted division really.”

Jimmy later participated in the Syrian campaign and the Malayan campaign, rising to the rank of a sergeant. He was discharged in October of 1944 after being hospitalised with malaria. After the war, he worked briefly on his family farm, as a linesman at Telecom, as a barman but eventually settled on a career running a butcher shop. He was heavily involved with his local community throughout his life. Among other things, he was the president of the Bellingen RSL as well as Grafton Services Club for 25 years. With his wife Margaret, he helped raise significant funds for Army Cadets. They had a son and a daughter and quite a few grandchildren. Throughout his life he remained very proud of his service in the war.

Private Alfred ‘Stony or Alf’ Stone

Alfred “Alf” Stone was a private in the 2/2nd Australian Infantry Battalion. He was born in Bungendore during the last year of the First World War. When the Second World War broke out, Alfred enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF).

“Time and time again, I couldn’t get a job, so I decided when the war broke out, I joined the army and left six weeks later to go overseas on the 10th of January 1940 and didn’t come back until 71 months later.”

Alf saw combat for the first time in the Battle of Bardia, in which Australian and allied forces won a great victory over numerically superior Italians. Not long after, traveling aboard HMAS Vampire, Alf and his battalion reached Greece. High on the slopes of Mount Olympus, Alf was tasked with supplying several units via donkeys. He liked to joke later:

“I was only a private, but I must have had the potential because up in Veria, the highest part of the Greek Alps, an officer put me in charge of three donkeys. Wow!”

He remembered a man from his unit, Sergeant Mickey Shelley, telling him: “Alf, this is going to be another Dunkirk. Sure enough, he was right.” Very soon, the prediction came true. In the middle of the night, Alfred and his comrades received new commands: “Come back to battalion headquarters, but before you do, set grenades and piss all over your blankets and leave them there.” On Anzac Day 1941, Alf was among those lucky enough to survive, but unlucky enough not to board the evacuation ships.

To make things worse, Alf was suffering from Bilatsia germ, which he picked up drinking snow water in the mountains. Unable to get medical treatment and with no supplies, he and his fellow soldiers attempted to cross the Corinth canal in search of alternative evacuation methods. They were less than a kilometre from the sea when the dive-bombers came in.

“The paratroopers dropped in front of us, hundreds of them. Not only parachutes… the gliders were unhooked, and they landed in front of us. The paratroopers landed in the trees; they landed in the wires in front of us.” Alf and his mates automatically turned around and ducked off the road underneath the trees.

As the Greek mainland was crawling with Germans, Alf managed to reach the town of Megara. Here he was happy to see an Australian ambulance truck:

“Thank God for that, we raced down to get this ambulance. For you, the war is over, get in the back, it’s driven by Germans. That’s how easy it is to become a prisoner. Little did we know, Max Schmeling [champion German boxer] had won a gold medal at the 1936 Olympics was in the ambulance, the front of the ambulance. So that’s another victory for Max Schmeling was to catch Tommy and Alf. Gone again. That was the start of 4 years, 13 days.”

What followed was not an easy experience for Alf or anyone involved. Prisoners of war were marched for days to Salonika with no food whatsoever. Alf was convinced that it was this starvation that got rid of the Bilatsia germ; however, when he received food for the first time, it came from the sheep killed in the bombing, which led to dysentery. Fortunately, his father was a medical worker, so he used his father’s advice and some olive oil he managed to find in order to survive. Many of the POWs did not.

“20,000 people in a minimum of space. Not being fed, not being looked after.” This is how Alf described conditions in POW camps in Corinth and Salonika. Eventually, Australian, New Zealander, Greek, Cypriot, and Yugoslavian prisoners of war embarked on an agonising train ride. After several days in railway cars in which there were no toilets and no room for laying down, they reached Austria, where Alf remained until the end of the war in Europe.

The camp in Austria had significantly better conditions than its ad-hoc counterparts in Greece; however, it was still quite a terrible place to be. Alf’s following anecdote portrays this well: “Had my appendix taken out; in those days, they didn’t have any anaesthetic, it was 1943. All the medical supplies from Germany and Austria went to the Russian Front. So they tied me down, arms and legs; there were five medical orderlies who held me down, and I lost my appendix.”

“The Germans held me in the prison camp in Austria for 4 years and 13 days, and after the war was over, I went to England by plane. Met a friend of my cousin’s who is now my wife. So, we got engaged… we’re still together.”

Alf was the president of the Newcastle POW Association.

Private Bernard ‘Barney’ Moore

Bernard ‘Barney’ Moore was born in Liverpool, England, in 1919. At the age of six, he moved to Auburn, Australia, with his family. A mere 14 years later, he volunteered in the Second AIF. Despite being a year too young for the required age of 21, he lied on his paperwork and enlisted as a private in the 2/2nd Australian Infantry Battalion, 6th Division.

In April 1940, he found himself in Greece, marching towards the border with Yugoslavia. At first, there was “no real fighting, just skirmishes, a couple of patrols here and there, but … then the battalion went up to Tempe Gorge, that was the Vale of Tempe. That’s where the Germans were making a breakthrough. There was only one New Zealand battalion up there, and they were getting knocked about, so we went up there. We delayed them for as long as possible,” Barney recalled.

Initially, Barney and his battalion were told that there were Canadian troops in front of them, which lifted their spirits because they did not expect Canadian troops in the area. However, they were in for a disappointing surprise: “The garbage they told us, about there being six thousand troops ahead of you, Canadians, and that. There were six thousand troops there, but they weren’t Canadians.” Barney remembered vividly his first encounter with German invaders as they were coming across the river into Greece: “they were coming across, like, unbelievable, in ranks, as if they were going on a picnic, the Germans. I lost a lot of men there. And then they got a tank across, and that was the end of it. They got one across, then they got another. Between them and Stukas, we really got a bit of a pasting there. Then the order came—every man for himself.”

Barney described the utter desperation of the situation: “They blew the Pommies, the RAF [Royal Air Force], out of the sky. You just don’t know what they were like. Everywhere you went, you had Me-110’s, they were knocking civilians, fleeing down the road, they were strafing them. They didn’t really have to, but they did. And every time you moved, they’d be on you. So that was Greece. We had no chance in the world. Not with what they threw at us.”

Barney’s battalion broke up, soldiers banded into smaller groups, and “different groups got out in different ways, any way you could.” Barney never forgot what “Greek people did, they gave us tucker that they could have had themselves, they fed us, they looked after us.” The Wehrmacht was still in hot pursuit; however, Barney and his mates eventually got a lift from the British, finally reaching Athens.

On 25th April, Anzac Day, they really made it an Anzac Day for us; they never let up. A day and a half they dive-bombed the port and that. They were sinking ships. That’s what, another thing I’ll never forget. Amid this chaos, the Navy organised evacuation, losing quite a few vessels, as Barney remembered. A ship he was evacuated on had been hit in the bow with a bomb, but it never exploded. It did, however, take both anchors and damaged the ship enough for it not to be able to reach the intended port of Alexandria. The swaying ship eventually pulled into Suda Bay, in Crete. Barney didn’t see any action on Crete and was eventually evacuated to Palestine, the very same place he departed less than a month earlier in order to reach Greece. This was not the end of fighting for him, however. He fought in New Guinea when he was discharged at the rank of a sapper mere days before the end of the war due to malaria.

Immediately after the war, he married Ruth, who he knew even before he enlisted. They had eleven children and numerous grandchildren. Barney was very proud of his service but did not want his children serving in Vietnam, as he thought it an unjustified war.

“I was just so proud of being a member of the 2/2nd battalion, cause it is a top battalion. Very, very good battalion. I think we were well officered, we were well drilled, well disciplined. And God bless them all.”

Stretcher Bearer Private Frederick ‘The Kid’ Williams

Frederick Williams was the son of a WW1 veteran from Sydney. When the war broke out, he was 17 years old but wanted to join, mostly from a sense of adventure. The Air Force was his preferred branch of service, but he was told he was neither sufficiently educated nor old enough. He didn’t feel like waiting four years, so he joined the 2/1st AGH (Australian General Hospital), as he heard they were looking for volunteers. Even then, his parents would have to sign off, but he forged their signature. His family was under the impression that he would stay in Australia until he was 21; however, unbeknownst to them, Frederick had joined the 2/2nd Australian Infantry Battalion as a stretcher bearer.

For him, the ocean passage was a relatively exciting affair; however, the death of a New Zealander who had to be buried at sea gave him a sense of the foreboding things to come. A visit to his ship from British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden left quite an impression on the young man. At the time, he and his mates believed they were going to England, where they would eventually strike at the Germans in France. After seeing the Suez Canal, he was beginning to think that was not the case, and before he knew it, he was carrying the wounded during the Battle of Bardia in January 1941.

Frederick described how stretcher bearers had to follow the infantry closely so they could react promptly to retrieve the wounded. Their job was not over even after the battle, and they helped carry both wounded Australians and Italians, as well as dressing their wounds. He remembered that they treated everyone and did not prioritise according to uniform but according to the seriousness of their wounds.

Frederick admitted to being frightened of battle, but that never stopped him from performing his duties. “The only people who didn’t get frightened were liars and idiots. I never struck any fellow who wasn’t frightened at some stage of it. Boy oh boy, I had my share of getting frightened. But you can’t do anything about it. You know, if you’re getting shot at, well that’s it. You just hope that if you get hit it be a nice one that either finishes quick or a little one that’ll get you back home.”

Frederick spent a week in the Battle of Tobruk before he was shipped out to Greece. From Athens, he went north with ANZAC troops who eventually faced Germans at the Battle of Tempe Gorge on April 18th, 1941. Frederick remembered mortars doing most of the action in the unit he was attached to until receiving orders to retreat. He acknowledged that some ANZACs would later claim that it was “every man for himself,” but he did not remember ever hearing those words nor seeing it in action until they reached the Corinth peninsula. Getting overrun by German forces, Frederick remembered being detached from his unit and helping anyone he could in the chaos that ensued. He later joked: “We were the first mob ever to lose Thermopylae Pass. The Spartans held in the early days. But anyway, they didn’t have parachutists in them days. So they sort of got behind, and we just kept going back and back, and we ended up at Daphne, where we first went to Greece.”

Eventually, seaborne evacuation was announced. Frederick and his mates were to be picked up by a British destroyer at the famous shores of Marathon, but this never happened. “No ship was safe because they had the dive bombers. They sank a lot of ships, those dive bombers… My mate and I, there were two of us ended up at that last part together after Tolo Bay and Marathon, just the two of us. Jack White and myself.” – Frederick explained.

What they decided to do then was head north to Yugoslavia on foot. They even discussed, with their fellow strugglers they met along the way, if they should look up Yugoslav royalists or communists. They have heard over the radio that evacuation was over and that what remained of allied troops from Greece was now on Crete. For days, they wandered the Greek countryside, evading German patrols, until they finally found a captain willing to take them to Crete, for the meagre sum of money they had on them.

On the way there, they stopped at the island of Milos where they were able to do some unplanned reconnaissance and find out that Germans were building an airfield. When Frederick and his mates finally reached Crete, they were not believed: “When we went ashore, the intelligence, the intelligence in name only, came and they said to us, our experience and we told them about Milos and they said, ‘No, they could not make an airstrip there capable of carrying heavy aircraft.’ I thought, ‘Yeah, all right, well you fellows know.’ That’s where they were doing their round trips. They could pick up troops and back, take them over and keep bringing them back. So that was their intelligence.”

Crete was eventually overrun by German paratroopers, but this time Frederick managed to find his spot on evacuation ships. He returned to the Middle East and finally ended up on the battlefields of New Guinea, which he found his most difficult experience during the war. Towards the end of the war, he returned to Australia to recover from his many wounds and malaria. While he was recovering, he heard the news of the war’s end.

Frederick admitted that the war changed him. He went for the adventure, but in the end, what he appreciated the most was camaraderie. Seeing his friends die left a deep impact on him: “Seeing what happened. Like, when you’ve seen, you know, people killed and blokes you see, really terrific fellows and next day someone says, “Oh, he’s dead.” You know, and this stretcher party with the crowd on it. There was Teddy Proudfoot, Stevie Dunn, Billy Sharman they were the band. And they were as fantastic fellows. You know, you could lose your wallet with them. And one shell comes along and wipes them out. And the poor fellow on the stretcher, too.” Despite all that he described that the most difficult experience in life was losing his wife at the age of 70.

Podcasts about Australians in the Mediterranean during WWII

Did my Relative Serve in these Battles?

Hundreds of thousands of Australians served in the Mediterranean during the Second World War. Some families know what their relative experienced during this often very important part of their life, but many do not. If you have a relative who served in the Australian armed forces during WWII and would like to know if they served in the Mediterranean please fill in the form below.

History Guild volunteers will research your relative’s service history and let you know what they find. As this is a free service provided by volunteers the timeframe may vary.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.