Reading time: 5 minutes

Despite many young Australians having a deep interest in political issues, most teenagers have a limited understanding about their nation’s democratic system.

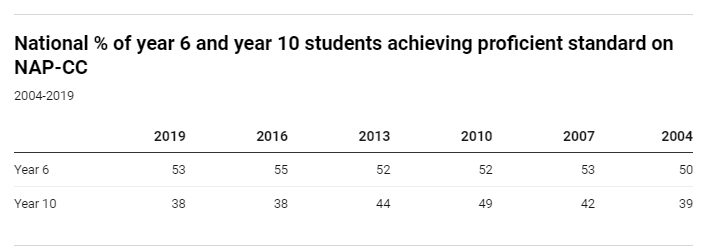

Results from the 2019 National Assessment Program – Civics and Citizenship (NAP-CC) released today show the proportion of young people demonstrating the expected level of knowledge about topics such as democracy and government has not improved since three years ago.

By Zareh Ghazarian (Monash University), Jacqueline Laughland-Booy (Australian Catholic University), and Zlatko Skrbis (Australian Catholic University)

Only 38% of year 10 students reached the standard of knowledge on civics and citizenship required for their year level in 2019, the same percentage as in 2016. In year 6, 53% achieved the benchmark, which is down from 55% in 2016.

This has implications for the confidence and preparedness of young people to participate in shaping society now, and into the future.

What is the civics and citizenship test?

The national assessment program on civics and citizenship has been held every three years since 2004. It is administered to a sample of year 6 and year 10 students across Australia. Around 13,250 students sat the assessments in 2019.

The NAP-CC seeks to assess students’ understanding of topics including Australian politics, government, history and the legal system. It also captures students’ knowledge of their rights and responsibilities as citizens.

The NAP-CC aligns with educational aims agreed to by national, state and territory education ministers.

The Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration, established in 2019, has two goals, the second of which is that:

young Australians become confident and creative individuals, successful lifelong learners, and active and informed members of the community.

What do the latest results show?

For year 6 students, the proficiency standard expects they can demonstrate knowledge of core aspects of Australian democracy. This includes awareness of the connection between fundamental principles (such as fairness) and their manifestation in rules and laws. They should also be able to demonstrate awareness of citizenship rights and responsibilities.

For example, students in year 6 should be able to identify the role of the prime minister, understand the origins of the Westminster system, and recognise that a vote on a proposed change to the constitution is a referendum.

At year 6, the percentage of students achieving the proficient standard has fallen slightly to 53% from 55% in 2016. This result maintains the established pattern where, since 2004, the percentage of year 6 students meeting the proficient standard has remained within the 50-55% range.

To meet the proficiency standards in year 10, students should be able to demonstrate knowledge of specific details of Australian democracy, make connections between the processes and outcomes of civil and civic institutions, and demonstrate awareness of the common good as a potential motivation for civic action.

Only 38% of year 10 students reached the proficient standard in 2019. This is the same as the last testing round in 2016, but well down on the 49% high achieved in 2010.

The NAP-CC 2019 results also showed:

- at both year levels, female students outperformed males

- there were large statistically significant differences between the achievements of non-Indigenous and Indigenous students

- students with parents who were senior managers or professionals had significantly higher scores than students with parents who were classified as unskilled labourers, or office, sales or service staff

- the scores of students from metropolitan schools were significantly higher than those of students from regional and remote schools at both year levels

- students who had a parent with a bachelor’s degree or above achieved more than 130 scale points (one proficiency level) higher than students whose parents completed year 10 or year 9 as their highest level of education.

What we need to do

Year 10 is the last year of compulsory schooling in Australia. It is also the final year in which the national civics and citizenship curriculum is delivered.

This means year 10 can be the last opportunity for students to learn about their nation’s political system and their responsibilities as citizens.

Previous research has also shown young people would like to consolidate their knowledge about Australia’s democracy before leaving school.

A national civics and citizenship curriculum was developed by the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority in 2012-2013. But states retain the constitutional authority over education, which results in variation in how civics and citizenship is taught across jurisdictions.

The latest data suggests now is the time to build on these investments and introduce targeted strategies.

When we spoke to school leavers in 2017, many told us they wanted additional lessons that concentrated on building their understanding of Australian democracy before they left school. In light of the consistently low performance at the year 10 level, it is now the time to capture and respond to the student voice.

We also need to support teachers. Young Australians have said what they learn at school about civics and citizenship is highly dependent on the preparedness of their teachers.

Teachers who are confident about exploring politics and government in class can have a positive impact on the learning outcomes of their students.

In what is often seen to be a “crowded curriculum”, teachers confront a range of challenges in delivering civics and citizenship lessons. As a result, there is value in providing opportunities to build their confidence and capacity in this space.

These latest figures show the previous results were no mere aberration and that student performance in civics and citizenship has remained low. The steps we take now will have an impact on Australian democracy for years to come.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Articles you may also like

A Voyage Towards the South Pole and Round the World – Audiobook

On his first journey Cook mapped the east coast of Australia, on his second the British Admiralty sent him into the vast Southern Ocean. Equipped with one of the first accurate chronometers, Cook pushed his small vessel not merely into the Roaring Forties or the Furious Fifties but become the first explorer to penetrate the Antarctic Circle, reaching an incredible Latitude 71 degrees South, just failing to discover Antarctica.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.