Reading time: 7 minutes

Warning: some of the following photos may be disturbing to readers.

The event traditionally defined as the Holocaust — by which I mean the systematic extermination of European Jewry between 1941 and 1945 — defies an overly simplified explanation.

With that being said, making sense of the who, what, where and when presents the somewhat easier task.

By Daniella Doron, Monash University

What happened in the Holocaust?

The Jews of Europe have been traditionally understood by historians as the principal targets of annihilation by the Nazis. Though Germans were perpetrators of this genocidal act, so too were other complicit Europeans, who either directly participated in murder or looked the other way.

Eastern Europe housed the sites of mass death (ghettos, labour camps, and concentration and death camps) built by the Nazis to “eliminate” Europe of Jews. Scholars generally point to 1941 – 1945 as constituting the woeful years in which approximately 6 million European Jews were killed by the Nazis.

The question of why the Nazis murdered the Jews of Europe remains somewhat thornier and far more controversial amongst scholars.

When the Nazis rose to power in 1933, the issue of how to handle the so-called “Jewish problem” ranked high on their agenda. The Germans held a racialised view of antisemitism, which defined Jews as not only biologically distinct from Germans, but also a critical threat to the health of the German nation.

Given their view of Jews as parasites, sapping the strength of the national body, the German Nazis experimented with a series of mechanisms to “eliminate” Jews from German life. The notion of murdering the Jews of Europe, we should note, had not yet surfaced.

Rather, in the early years of the regime, the Nazis saw emigration as an acceptable solution to the Jewish problem.

Legislation that disenfranchised Jews, stripped them of their financial assets, and denied them their livelihoods sought to clarify to Jews their new degraded position within Germany. The days of their security, stability, and equality under the law had come to an end. It was time to make a new life elsewhere. But these measures failed to bring about the results desired by the Nazis.

By 1939, slightly more than half of German Jews had decided to chart a new course abroad. Unfortunately, the outbreak of war the same year only served to exacerbate the dilemma of eliminating Germany of Jews within its domain.

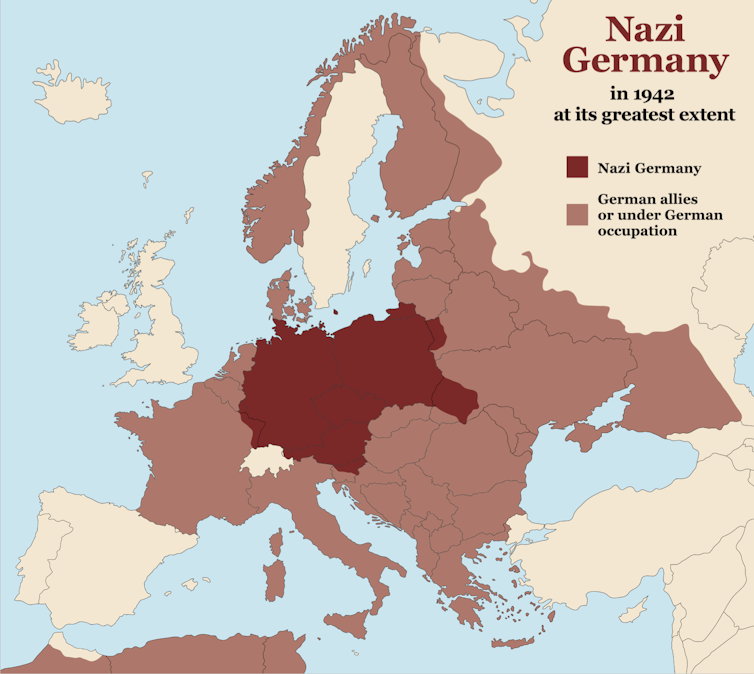

As Germany quickly and violently occupied large swaths of territory in eastern and western Europe, the number of Jews in its territory exploded. Whereas the population of Jews in Germany in 1933 stood at roughly half a million, approximately nine million Jews resided in Europe as a whole.

Emigration no longer seemed like a viable option. Which nation would be the new home to all those Jews? As it stood, the half a million Jews of Germany struggled to find nations willing to house them.

And it was soon decided that new solutions needed to be found.

The impact of the Holocaust

Scholars debate why and when and even who arrived at the new solution of mass murder to solve Europe’s so-called “Jewish problem.”

We know that in 1939, when war broke out in the East and Germany occupied Poland, the Nazis turned to the creation of ghettos in Poland, which served to concentrate and isolate Jews from the greater Polish non-Jewish population. In these ghettos, often surrounded by high walls and gates, Jews engaged in forced labour and succumbed in great numbers to starvation and disease.

We also know that in 1941, when war broke out with the Soviet Union, the Nazis turned to rounding up Jews in the towns and villages of eastern Europe and murdered them by bullets. At least 1.6 million eastern European Jews died in this fashion. But why this turn from “passive murder” in the ghettos to “active murder” in the killing fields and later the concentration and death camps of eastern Europe? Who proposed this radical solution?

These questions defy scholarly consensus. It may be that the earlier policies of emigration, isolation and concentration of Europe’s Jews were eventually perceived as insufficient; it may be that the murder of Europe’s Jews by starvation and later bullets proved too slow and costly. And perhaps it was not Hitler who first arrived at the idea of mass murder, but Nazi bureaucrats and functionaries working on the ground in eastern Europe, who first conceived and experimented with this genocidal policy.

Regardless, by 1942, Jews across Europe were rounded up — from their homes, their hiding places, and Nazi run ghettos and labour camps to be deported to killing centres and concentration camps, where the vast majority lost their lives.

Contemporary implications

The legacy of the Holocaust has loomed large for more than 70 years, and continues to inform our culture and politics. It has come to be seen as arguably one of, if not the, defining events of the 20th century.

The Holocaust is commonly perceived as a truly rupturing occurrence in which a modern state used the mechanisms of modernity — technology, scientific knowledge and bureaucracy – not for the benefit of humanity but to inflict suffering and death.

We are now well aware that modernity does not necessarily result in progress and an improved standard of living, but that it comes with a dark underbelly that can lead to the violent purging of segments of society perceived as undesirable.

In its aftermath, the Holocaust became paradigmatic for defining genocide. The murder of European Jewry inspired the term “genocide”, which was coined by the jurist Raphael Lemkin in 1944. It later prompted the Genocide Convention agreed to by the United Nations in 1948.

The 1948 Genocide Convention, the memory of the Holocaust, and the phrase “never again” are thereby routinely invoked in the face of atrocity. And yet these words ring hollow in the face of genocides in Rwanda, Cambodia, Bosnia, and the current genocide against the Rohingya in Myanmar.

It happens again and again. Not to mention that the largest refugee crisis since the second world war is occurring this very moment as desperate Syrians undertake perilous journeys across the Aegean.

Approximately 80 years ago, Nazi persecution likewise culminated in an international refugee crisis. World leaders recognised the plight of Europe’s Jews during the 1930s and into the 1940s, even if they could not foretell their eventual genocidal fate.

International leaders even convened a conference (the Evian Conference) in which they debated how best to aid German Jews. Country after country expressed their sympathies with Jewish refugees but ultimately denied them refuge.

International news at the time closely followed the journey of the SS St Louis, as it sailed from port to port with 900 Jewish refugees unable to disembark because nations refused to grant asylum. We now know the future that befell many of these refugees.

These days, images of desperate Syrians undertaking perilous journeys across the Aegean, or the Rohingya fleeing their persecution in Myanmar, occupy our front pages. As we contemplate our responsibility towards these desperate individuals, the SS St Louis and the Evian Conference have been routinely invoked in our public discourse as a reminder of the devastating consequences of restrictive refugee and immigration policies.

We must remain haunted by our past failings. It is the legacy of the Holocaust that compels us to examine our responsibility to intervene and turn our attention to the plight of refugees. And we should consider whether that legacy has remained sufficient or whether we need a reminder of the dire consequences that comes with numbing ourselves to the suffering of others.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Articles you may also be interested in

Deceptive Ineptitude: German Spies in WW2 Britain

DECEPTIVE INEPTITUDE: GERMAN SPIES IN WW2 BRITAIN Operation Lena, the German espionage operation in Britain, turned out to be one of the least successful spy missions of World War 2. By Madison Moulton Plotting an invasion of the United Kingdom in 1940 – codenamed Operation Sea Lion – the Nazis sent spies to gather intelligence […]