THE END OF APARTHEID

Reading time: 8 minutes

Racial divisions emerged in South Africa as early as the 1600s, due to Dutch settlement. It began with the Europeans maintaining segregation and hierarchy between themselves, their slaves (many from Asia), and local African populations.

Once the Cape of Good Hope was seized by the British during the Napoleonic period, race-based policies in the colony became increasingly formalised.

The 1806 Cape Articles of Capitulation, which secured the Dutch settlers’ surrender in exchange for the protection of their existing rights and privileges, bound the British to respect prior Dutch legislation and gave segregation an enduring place within the legal system of the South African colonies.

By David Robinson, Edith Cowan University

What happened?

Under British control during the 1800s, various laws were passed to limit the political, civil and economic rights of non-whites in South Africa.

This included denying them the right to vote, limiting their right to own land, and requiring the carrying of passes for movement within colonies.

Despite resistance to discriminatory laws in the first half of the 20th century by groups like the African National Congress (ANC), these laws persisted over the decades.

However, social change accelerated in South Africa during the second world war, with African labourers increasingly drawn to urban areas. This was due to industrial production increasing to service Europe’s wartime demands for minerals and local manufacturing replacing imports, empowering rebellious workers and ANC activists in the process.

The threat of social change was palpable, leading South Africa’s white population to elect the Afrikaner-dominated Herenigde Nasionale Party (National Party) in 1948, over the more progressive United Party.

The National Party, which then ruled South Africa until 1994, offered white South Africans a new programme of segregation called Apartheid – which translates to “separateness”, or “apart-hood”.

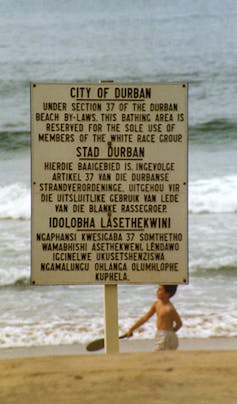

Apartheid was based on a series of laws and regulations that formalised identities, divisions, and differential rights within South Africa. The system classified all South Africans as “White”, “Coloured”, “Indian”, and “African” – with Africans classified into 10 tribal groups.

From 1950, the Population Registration Act and the Group Areas Act assigned all South African citizens a racial status, and determined in which physical areas of South Africa different races could live.

Future legislation would embed these regional divisions, and provide a façade of self-government for the African regions.

The 1949 Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act and 1950 Immorality Act outlawed interracial romantic relationships, and by 1953 the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act and Bantu Education Act segregated all kinds of public spaces, services and amenities.

Racial policies also intermingled with rhetoric against communism. The 1950 Suppression of Communism Act was central to banning any party advocating a subversive ideology. Virtually any progressive opponent of the National Party regime could be defined as communist, particularly if they disrupted “racial harmony”, which severely limited anti-Apartheid activists’ ability to organise.

More generally, the government also maintained very socially conservative laws for all citizens regarding sexuality, reproductive health, and vices like gambling and alcohol.

The impact of and response to apartheid policies

In this context, the ANC youth wing (including a young lawyer by the name of Nelson Mandela) came to dominate the party and adopt a confrontational black nationalist programme. This group advocated strikes, boycotts and civil disobedience.

In March 1960, police attacked a demonstration against Apartheid’s racial pass system in the Sharpeville township. They killed 69 people, arrested over 18,000 more, and implemented a ban of the ANC and the smaller Pan-Africanist Congress.

This pushed resistance towards more radical, underground tactics. Following authorities’ further brutal treatment of a 1961 labour strike, the ANC launched armed struggle against Apartheid through a military wing: Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK). As a leader of MK, Nelson Mandela was arrested in 1962 and subsequently sentenced to life in jail.

Anti-Apartheid resistance dimmed during the 1960s due to the harsh repression of activist activities and the arrests of many anti-Apartheid leaders. But in the 1970s, it was revitalised by a growing Black Consciousness Movement.

The independence of nearby Angola and Mozambique from Portugal, and discriminatory education policies that led to the 1976 Soweto Uprising, were hopeful examples of change. By the 1980s, township rebellions, boycotts, union militancy, and growing political organisations pushed South Africa’s Botha government into a state of emergency, forcing dramatic concessions that escalated to negotiations with Mandela.

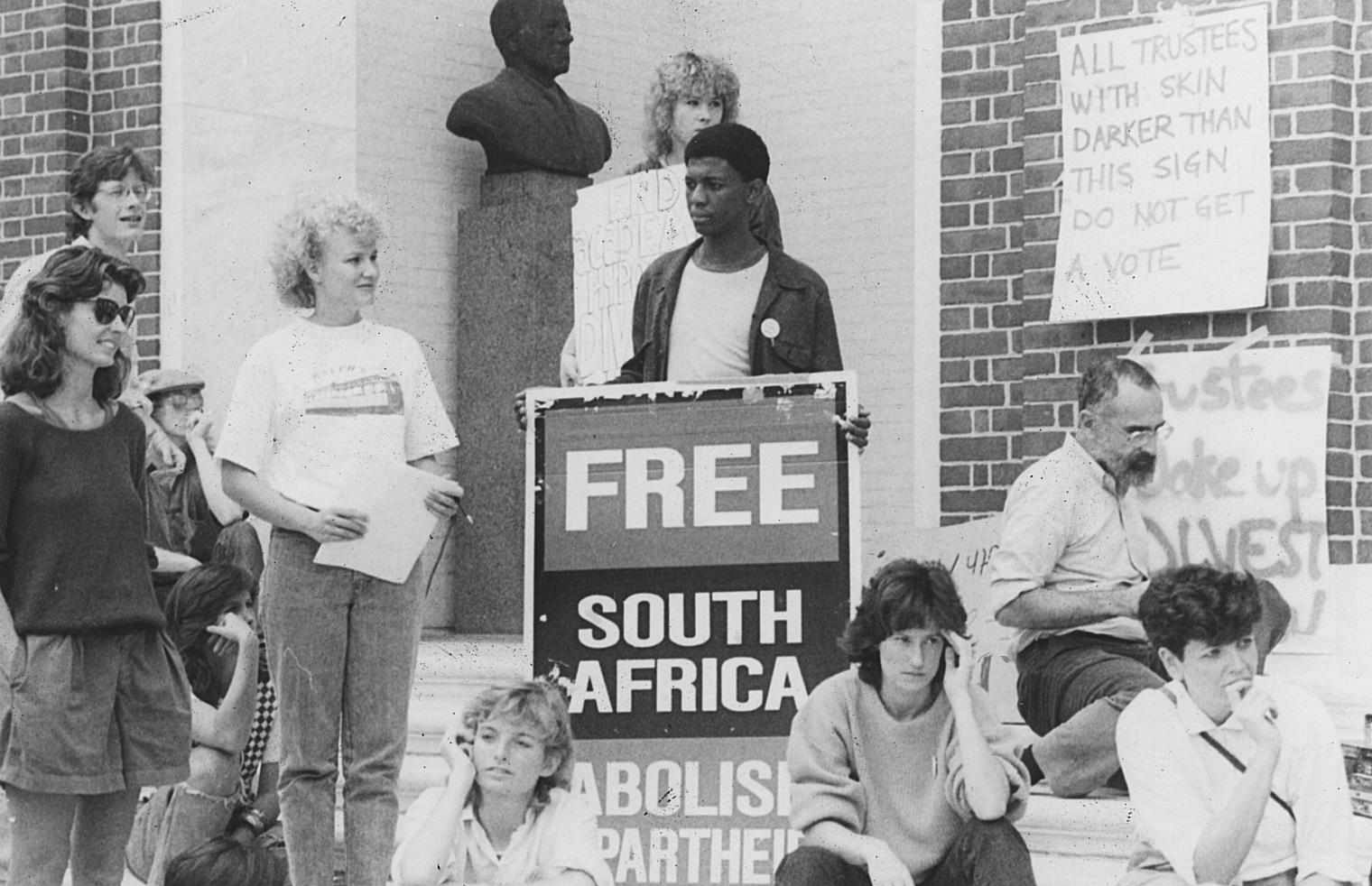

Despite the British and American governments classifying the ANC as a terrorist organisation during the 1980s, the growing international criticism of Apartheid, spurred by disruptive resistance in South Africa, and the undermining of the anti-Communist imperative due to the end of the Cold War, also moved those states to finally implement trade sanctions against Apartheid.

In 1990, President Frederik de Klerk freed Mandela and unbanned anti-Apartheid political parties, to allow negotiations for a path to majority-rule democracy.

Despite right-wing backlash and outbreaks of violence, the white minority did overwhelmingly approve negotiations for democratic transition. Mandela sought peaceful racial reconciliation, through a negotiated process of transition to free, inclusive elections, and the post-Apartheid operations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Receiving the 1993 Nobel Peace Prize and then winning South Africa’s 1994 elections, Mandela was thus personally integral to the peaceful transition from Apartheid to multiracial democracy.

Contemporary relevance

What legacy has the end of Apartheid thus left?

Globally, Mandela became an icon, associated with resistance, justice, and Christ-like self-sacrifice. The popular perception of Mandela and the anti-Apartheid movement, though acknowledging some elements of the struggle’s history, generally demonstrates a shallow understanding of what actually occurred.

These narratives predominantly fail to engage with Mandela’s leadership of military struggle, and the widespread militant, and violent, action that forced the Apartheid regime to negotiate. They often highlight international campaigns against Apartheid, but are mute on the strong military and financial support for Apartheid South Africa by western states throughout the Cold War.

While leaving a general message that opposition to injustice can win, the anti-Apartheid movement’s history encapsulated by Mandela is probably as well understood as the iconic image of Che Guevara printed on t-shirts.

Regionally, the end of Apartheid ended much of Southern Africa’s conflict, and allowed black-ruled states to unite in far greater cooperation for social and economic development.

The intervention of South African troops (and mercenaries) throughout Africa was also greatly reduced. However, conflict has continued in many areas of Africa, as have operations of the African Union and increasingly the United States’ Africa Command.

Meanwhile, though still a regional hegemon, post-Apartheid South Africa failed to effectively support neighbouring democracies, allowing questionable regimes such as Mugabe’s ZANU-PF in Zimbabwe to persist without adequate intervention. Newly stable southern Africa was also increasingly open to trade and investment from China – their enhanced global reach and influence an unforeseen result of freedom in many developing countries.

Nationally, though entering power with principles seeking redistribution of wealth and a general raising of living standards, the ANC gradually embraced neoliberal policies that have only led to an increase in poverty and inequality in South Africa over the past two decades.

The ANC’s overwhelming dominance of government throughout this period – with an absolute majority – has stifled development of effective parliamentary democracy (though South African civil society remains vibrant and active). And corruption throughout the ANC and the South African state has become endemic. Though narratives of “white genocide” in South Africa are not supported by facts, although crime and racial enmity remain virulent in South African society. But, South Africa also persists as one of the world’s most multicultural and inclusive countries.

Despite its troubles, South Africa is a nation with an inspiring story of struggle – even though an accurate vision of the country’s past and present requires engagement with many complexities.

The South African example shines a light on sometimes unpleasant realities of history, as well as enduring aspects of human nature. For those who are willing to seek out the details and contemplate the contradictions, the end of Apartheid leaves a legacy of insight most valuable in our turbulent age.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Articles you may also be interested in

Churchill and India: imperial chauvinism left a bitter legacy

For those who enjoy debunking the reputations of national heroes, there can be few softer targets than Winston Churchill. The phrase “flawed hero” could almost have been invented to characterise his long, wilfully erratic career. Running through it, like some bitter-tasting lettering in a stick of rock was a strain of extreme imperial chauvinism. Indeed, […]

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.