Reading time: 7 minutes

For service or for gallantry, almost all modern militaries – especially Western militaries, have issued war medals for a very long time.

But who decides who gets these medals and awards, and how?

Recent examination has brought to light a distinct lack of minority soldiers within Western militaries winning bravery awards, across many different countries, all throughout the 20th century and beyond.

By Mark McKenzie

What Medals?

Since before the First World War, various Western countries such as France, the USA, Britain, and Australia have maintained two types of military medals.

The first type is service medals or awards – the ones without any real controversy. These Medals such as the Australian Service Medal 1939-1945, the French 1901 China Expedition Commemorative Medal, or the American Defense Service Medal are awarded to any soldier who meets the objective criteria of serving on a particular front during a specific time frame.

No subjective decision – just a simple checklist.

The second type is the medals for bravery, gallantry, heroism, and self-sacrifice. Often awarded posthumously, these medals are awarded to soldiers who have have conducted themselves heroically.

Of course, not everyone gets these medals. Medals such as the British Victoria Cross (or for an Australian soldier now, the Victoria Cross For Australia) are extremely rare. Since 1856, only 1,358 people have been awarded the Victoria Cross.

Similarly, of 40 million service members across its history, only 3,517 Americans have been awarded the Medal of Honor – America’s greatest military medal.

But awarding these medals doesn’t involve an objective checklist – some individual or group of individuals has always had to decide who receives them.

How Does Awarding Medals Actually Work?

Although the exact process depends on the country, the selection of recipients for medals of gallantry and honour typically involves a commanding officer recommending someone under their command for a particular medal.

For the Victoria Cross in Britain, a commanding officer recommends someone, the VC committee then selects and further recommends further candidates before the sitting Minister of Defence selects the awardees. The MoD then recommends the awardees to the Crown, who hands out the medals.

Similarly in America, people can be nominated for the Medal of Honor through the chain of command, or in some cases by members of Congress. Once awarded, the President presents the medal.

Presidents, committees, the chain of command – all of these layers rely on individuals with personal biases making subjective decisions on who is deserving of awards.

And across modern history, these decisions haven’t always been fair.

The State of Racial Discrimination – From WW1 to Today

In World War Two over a million African-American men served, yet not a single one won the Medal of Honor.

While today 94 African-Americans have received the Medal of Honor, it seems clear that a history of racism within the United States Military initially prevented minority soldiers from receiving awards.

According to historian Robert Child, there are multiple examples of African-American soldiers such as Ruben Rivers who were deserving of the Medal of Honor, yet the military establishment refused to accept nominations for African-American soldiers.

“Most white officers in WW2 desired to submit their deserving black soldiers for the medal of honour, but it was an unspoken rule … that no black soldiers would be recommended for the highest honour.” – Robert Child on The WW2 Podcast

There was no specific code or law preventing minorities from being nominated for the Medal of Honor, but as Child outlines, the establishment generally rejected the notion. This is further seen in the divisive 1925 Army War College Report called The Use of Negro Manpower in War, which argued emphatically that Black men were genetically inferior, less intelligent, and less fit for duty than white men.

Though not gospel, this report served largely as a guideline for the treatment of minorities in the US military until the introduction of the Tuskegee Airmen in 1941.

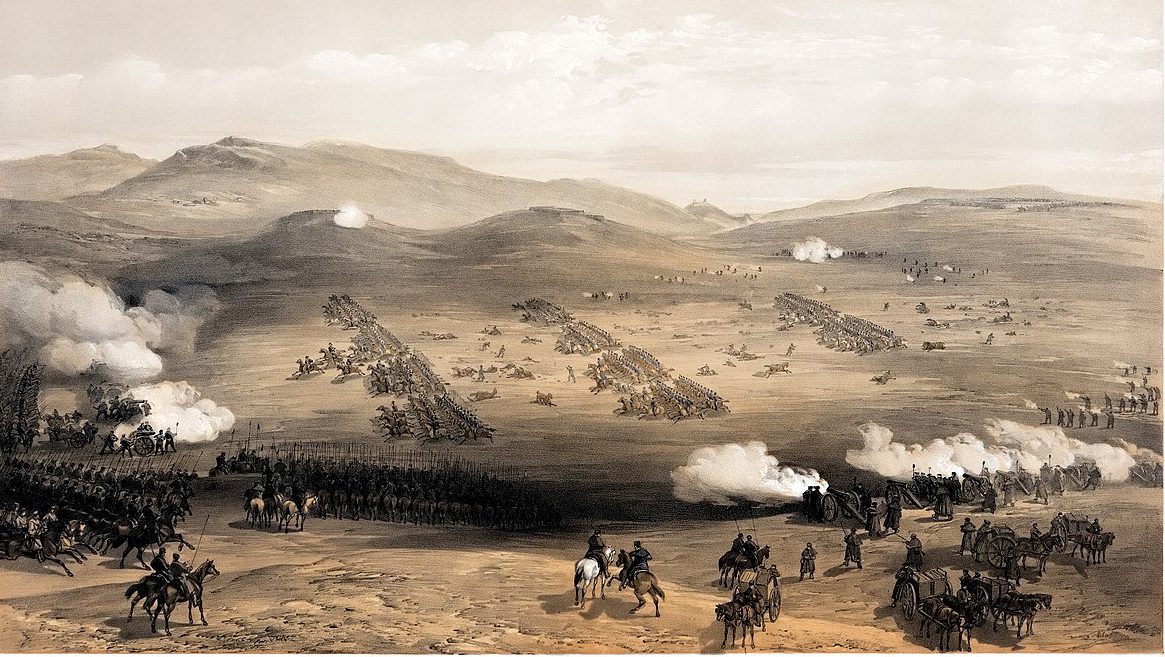

A similar system can be seen in the British and French militaries, with soldiers from Africa, the Caribbean, and the Indian subcontinent consistently serving with distinction, enduring harsh conditions and formidable adversaries, yet receiving relatively few medals.

This can be seen clearly with the French Médaille Coloniale – a medal specifically awarded to those who fought in/for the French colonies or protectorates, especially during WW2. Despite this, the majority of the awards went to white French soldiers, and relatively few to soldiers of a darker hue.

A similar sentiment of commanding officers putting forward minority soldiers for awards can be seen as early as WW1 in the British military, as was the case with Black British Second Lieutenant Walter Tull.

For his acts of gallantry on the Italian front, Tull was put forward for a Military Cross award, with his comrade writing that “he had been recommended for the Military Cross, and certainly earned it”.

The British Ministry of Defence claimed they never received the recommendation.

Do Things Start to Change in WW2?

World War II heralded a shift in attitudes towards racial integration within the military. In the United States, the need for manpower led to the gradual integration of Black soldiers into mainstream units. The formation of the Tuskegee Airmen, the first African American aviators in the U.S. military, and the valour displayed by Black infantry units highlighted the combat prowess of minority soldiers.

While no Medals of Honor were awarded, multiple African-American soldiers received various other awards such as the Distinguished Service Cross, highlighting, as Child argues, a shift in the on-the-ground attitudes towards recognizing minority achievements in war.

Similarly, within the British Empire, the participation of colonial troops in WW2 showcased the resilience and bravery of diverse soldiers. Indian, African, and Caribbean units played pivotal roles in key battles, demonstrating their combat capabilities and earning respect from their allies.

Though many British colonial troops did receive medals from the British Empire during WW2, British Military historian Dr Robert Lyman MBE has researched the ratio to which colonial troops received awards compared to White British troops in Burma.

Counting all 474 awards between 1942 and 1945, Lyman calculated that White British troops made up 19% of the Burma force, yet received 47% of the awards for honour and gallantry.

This was compared to Indian soldiers at 64% of the force but only 45.4% of awards, and Black soldiers at 17% of the force but only 7.6% of the medals.

What Now?

Racial discrimination in giving awards is still an issue many modern militaries face. However, work is being done to challenge internal bias and award those who truly deserve it. Some of those who were unfairly denied awards for their valour have received posthumous awards, such as several African-American soldiers from WW2 who received their Medals of Honor in 1997.

We can’t go back in time, but by looking back at history we can work to reduce racism in the of award of military honours.

Podcasts about Racial Bias in Military Bravery Awards

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 54

The History Guild Weekly History Quiz.See how your history knowledge stacks up. Have an idea for a question? Submit it here and we’ll include it in a future quiz! Please leave this field emptyTell me about New Quizzes and Articles Get your weekly fill of History Articles and Quizzes We won’t share your contact details […]

Flies, filth and bully beef: life at Gallipoli in 1915

Reading time: 6 minutes

Many factors contributed to making the Gallipoli battlefield an almost unendurable place for all soldiers. The constant noise, cramped unsanitary conditions, disease, stenches, daily death of comrades, terrible food, lack of rest and thirst all contributed to the most gruelling conditions.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.