Reading time: 6 minutes

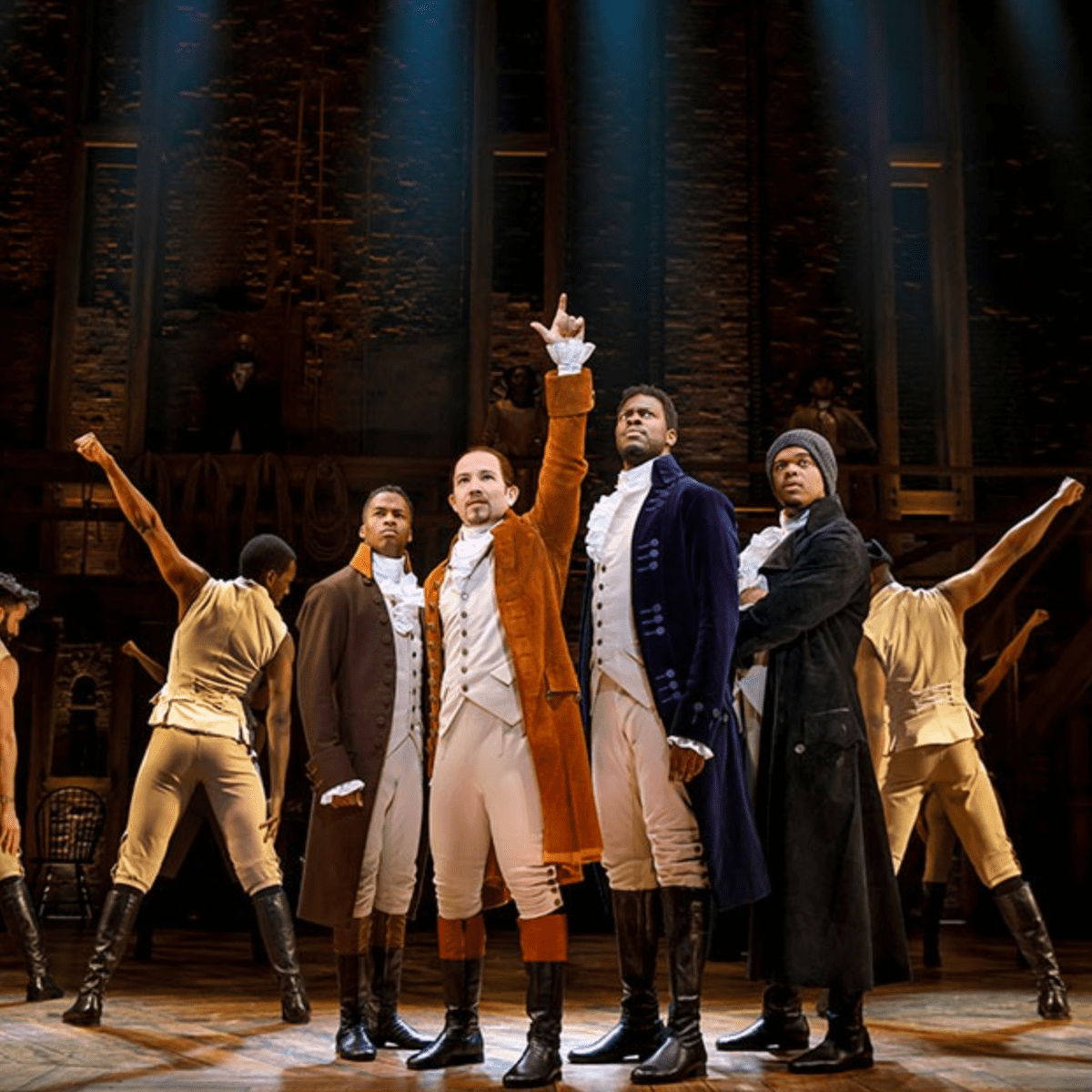

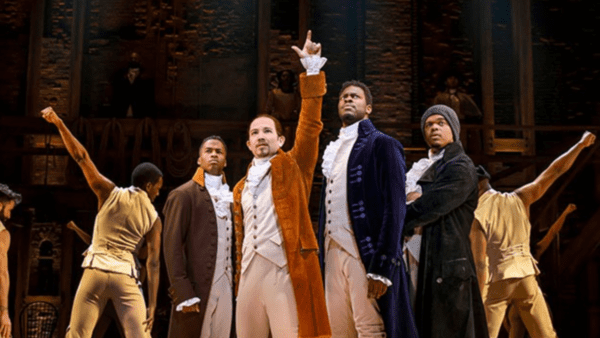

It’s important to take historically-based art, whether a painting that condenses a battle or the acclaimed Broadway smash Hamilton: An American Musical, with a grain of salt. Rather than expecting these works to look at history through the factual lens of a primary source, they should be taken as an altered view of history designed to generate the interest of the masses.

By Carolyn Comeau.

The interpretation of history is rarely, if ever, a neutral undertaking. The life experiences, biases, and interests of any student shape their understanding of the past. Artists who set paintings, plays, and films in the past are not immune to this, and it’s wise for audiences to take into account that history will likely be manipulated, either subtly or obviously, for the sake of art.

A prime example of this is how playwright Lin-Manuel Miranda, creator of the Broadway smash hit Hamilton, conceived of and structured his musical, set during the time of the American Revolution.

What research did Lin-Manuel Miranda do?

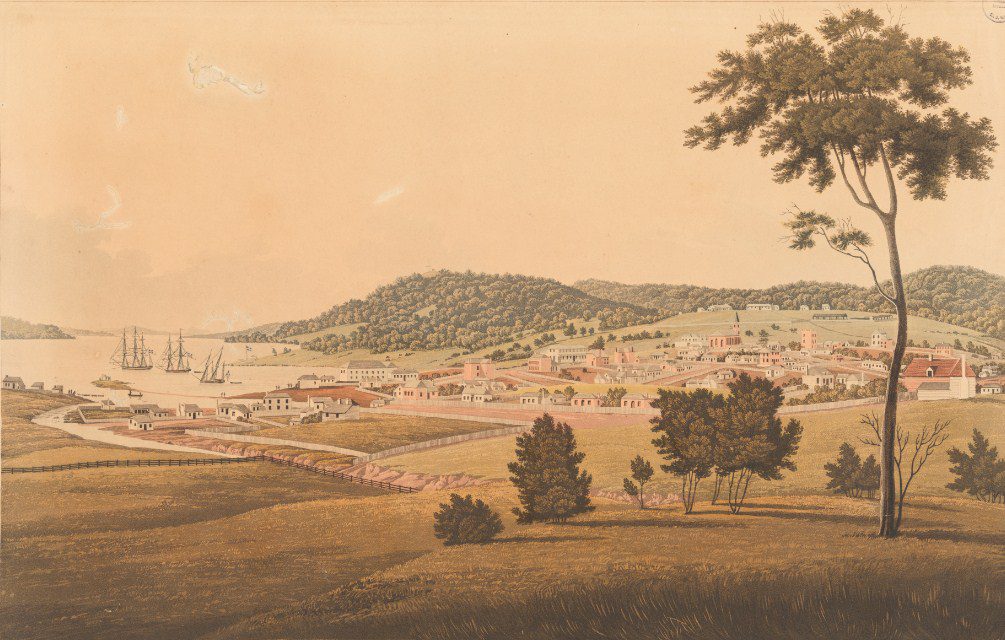

Though Miranda has admitted that he had to balance factual storytelling with high-impact drama to create a theatrical work that audience members would find engaging, he should get credit for turning to Pulitzer Prize-winning Hamilton bigorapher Ron Chernow’s best-seller, Alexander Hamilton, as his most relied upon source of information as he created the show. Chernow’s exhaustive deep dive into Hamilton’s turbulent early life in the West Indies, rise to success in the newly formed democracy of the United States, and how his being consumed with the Constitution’s content and intent led him to co-author The Federalist Papers.

Where does Hamilton exercise artistic licence?

Miranda cast many people of color in roles of historical figures known to be white, however this is a deliberate effort on his part to allow those who couldn’t tell their stories for centuries to finally get the chance.

Miranda reimagines some aspects of Hamilton’s relationship with his late-in-life nemesis, fellow Founding Father Aaron Burr. They were certainly born into different circumstances, though both lost their parents through death and in Hamilton’s case, abandonment, early in life. Burr came from a more privileged economic background, while Hamilton came to New York in his teens to gain education. Both also happened to serve in the colonial army and were at Valley Forge together, enduring the harshest of winters with few supplies and little sustenance, but their later lives diverged considerably.

It was not only opposing politics that caused the enmity between them to grow, it was Hamilton’s anger at the fact that Burr had the audacity to run against his own father-in-law, Philip Schuyler, for a New York state Senate seat. Hamilton wasn’t just insulted for reasons of family honor, however; he was shrewd enough to know that had his father-in-law won, Philip would have been more supportive of Hamilton’s policies.

Hamilton and Burr were not as closely connected as Hamilton portrayed them, and the events that led up to their duel during which Hamilton lost his life, reflect more of a slow burn of cumulative quarrels and grudges than a sudden injury to an alliance between friends who were closely connected for a long time.

Another aspect of the play that diverges from Hamilton’s life is his relationship with his sister-in-law, Angelica Church. His wife Eliza’s older sister was married to a wealthy English businessman John Barker Church several years before Hamilton and Eliza met. Angelica also had three brothers and married against the wishes of her father. This is the complete opposite of the play’s portrayal, which has her singing that her ‘father has no sons‘ and ‘her only role is to marry rich’. While it’s true that written correspondence between Hamilton and Angelica reflects a familiar, even affectionate relationship, she also wrote letters in a similar tone to Thomas Jefferson.

Retelling of the American foundation myth

The first half of the play is an uncritical retelling of the American foundation myth rather than historical reality. It continuously refers to ‘the British’, when most American Colonists at this time considered themselves to be British. It dismisses opposition to revolution by any American Colonists, despite the fact that at around 20% of the white colonists actively opposed revolution. It portrays the revolution as being overwhelmingly supported when in reality only 40 to 45% of the population supported it.

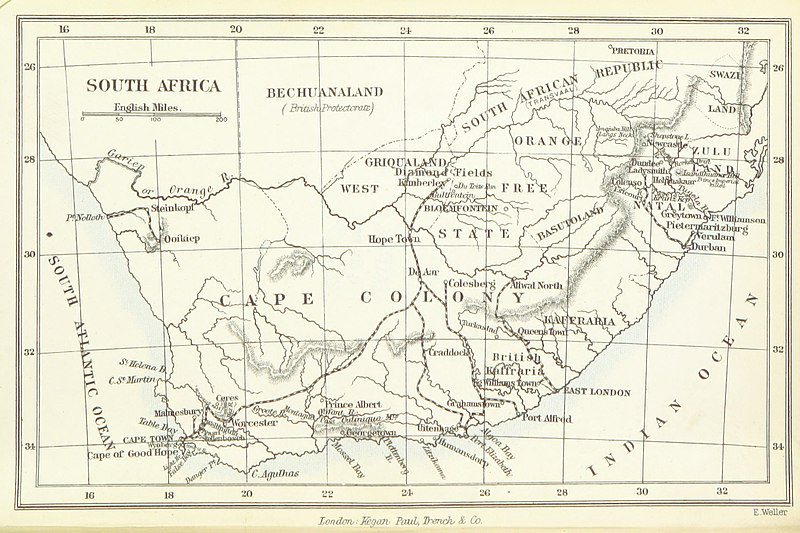

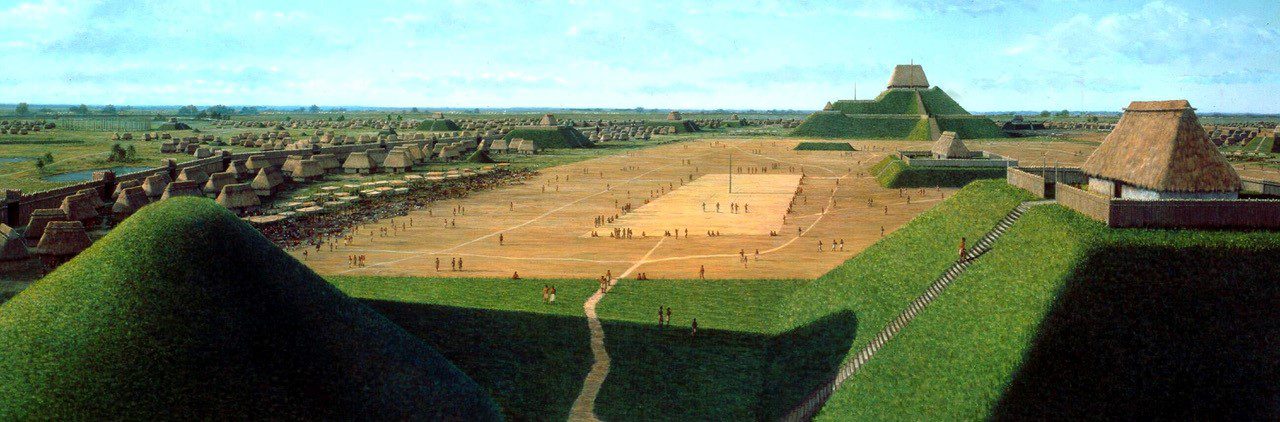

Hamilton neglects to mention the root causes of the war in the colonists expansionist desires being frustrated by treaties made with Native American peoples that supported the British in the French and Indian War (Seven Years War). The colonists coveted the land the Native American’s had been allowed to retain and were angered that the British Government supported the Treaty rights of the Native Americans. It also gives the standard ‘taxation without representation’ reasoning for the conflict which has validity, but is simplistic without mentioning why that taxation was being introduced, which was to recoup some of the cost of defending the colonies from the French.

The Whitewashing of Alexander Hamilton

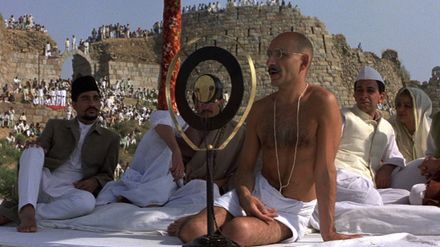

Miranda presents Hamilton as a more progressive figure with regard to slavery than he was. Hamilton was more progressive than some other Founding Fathers but he was far from an activist. Not only did Hamilton marry into the wealthy slave-holding family of his wife Eliza Schuyler, he bought and sold human beings for his in-laws. Despite being a founding member of the New York Manumission Society, whose mission was to work toward gradual abolition of slavery in the state of New York, his actions don’t reflect much credit upon him. His stance on personal property rights also hindered movement towards abolition. Miranda evidently wanted Hamilton to be a character the audience could feel positive about and portrayed him as such. This video explores this aspect of Alexander Hamilton’s life.

Miranda told Alexander Hamilton’s story in an innovative way, and may have piqued an interest in American history for many who wouldn’t have been drawn to it otherwise. Artists take liberty with history in order to present their vision, but it’s important to remember that this doesn’t necessarily reflect reality. A compelling play requires a more idealised character rather than the unvarnished and flawed individuals reality.

Hamilton perpetuates the myth of America’s founding, but can also be credited with driving those who experience the play to learn more about this time in history.

Articles you may also like

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.