Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

New techniques for dating volcanic eruptions, a lone axe and Indigenous oral traditions give us a new minimum age for human occupation in Victoria.

By Dr Erin Matchan and Professor David Phillips, University of Melbourne

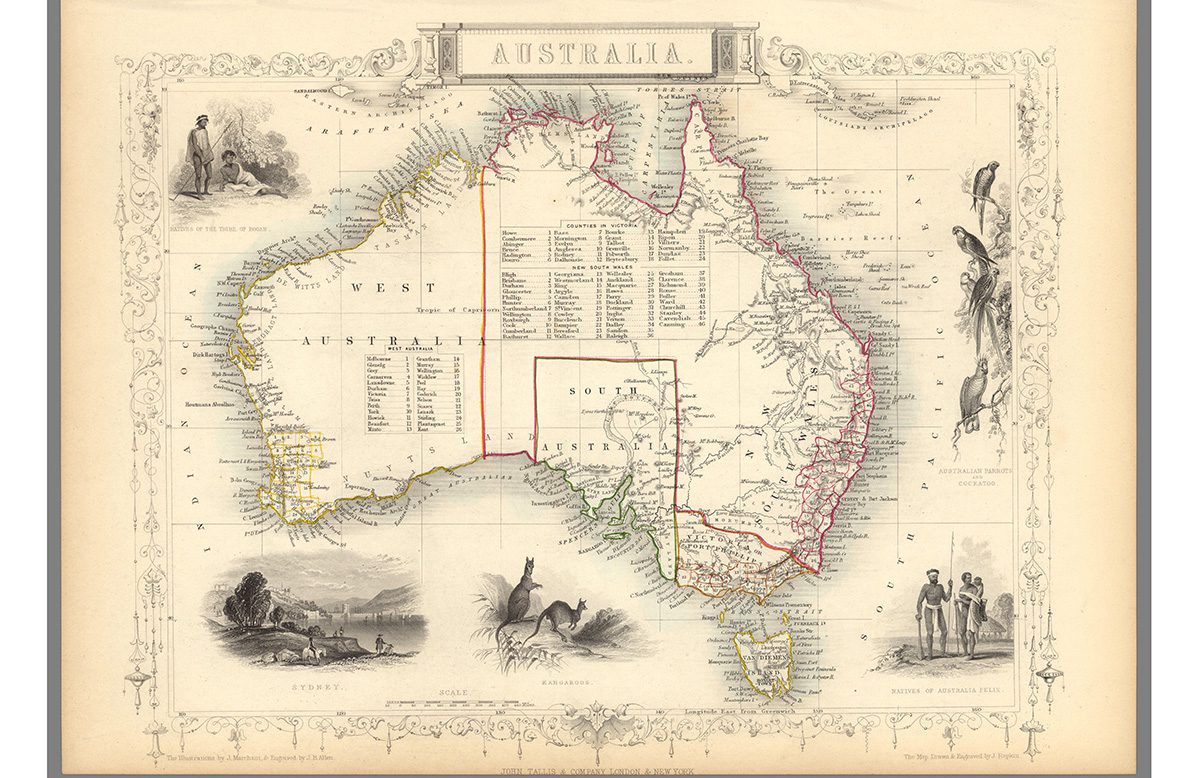

The questions of when people first arrived in Australia and the nature of their dispersal across the continent are subjects of ongoing debate.

A lack of ceramic artefacts and permanent structures has resulted in an apparent scarcity of dateable archaeological sites older than about 10,000 years, yet what evidence there is suggests occupation across much of the continent for 30,000 or more years.

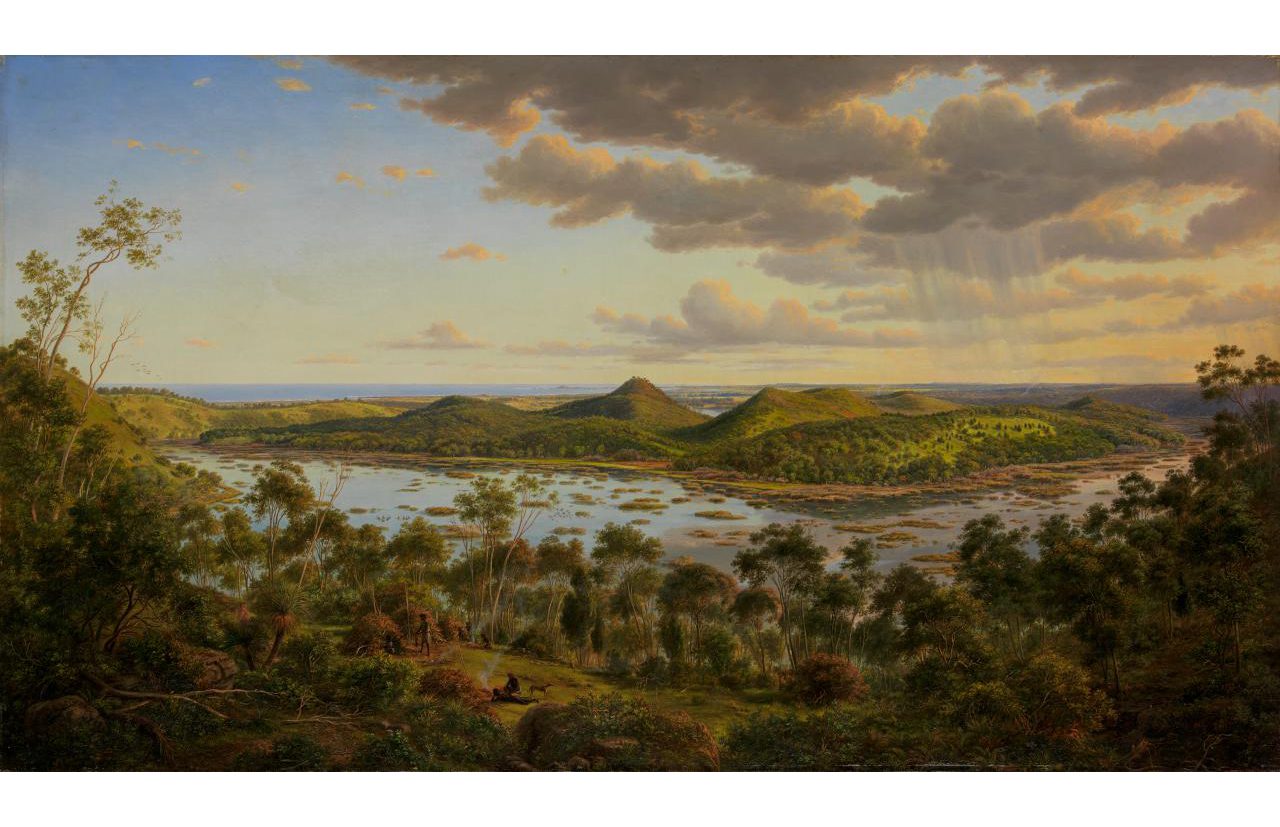

In western Victoria, the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape World Heritage Site in Victoria contains the world’s oldest known aquaculture system, built by the Gunditjmara People more than 6,000 years ago, near a volcano called the Budj Bim Volcanic Complex.

However, the Gunditjmara have lived in this area for much longer than this, and now, using a new volcanic activity dating technique and matching this with physical archaeological evidence and the rich oral traditions of the Gunditjmara people – we have confirmed human habitation in this region at least 34,000 years ago.

Existing evidence for the oldest known human habitations in Australia comes largely from radiocarbon (¹⁴C) dating of charcoal, and optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating of quartz grains in rock shelter sediments.

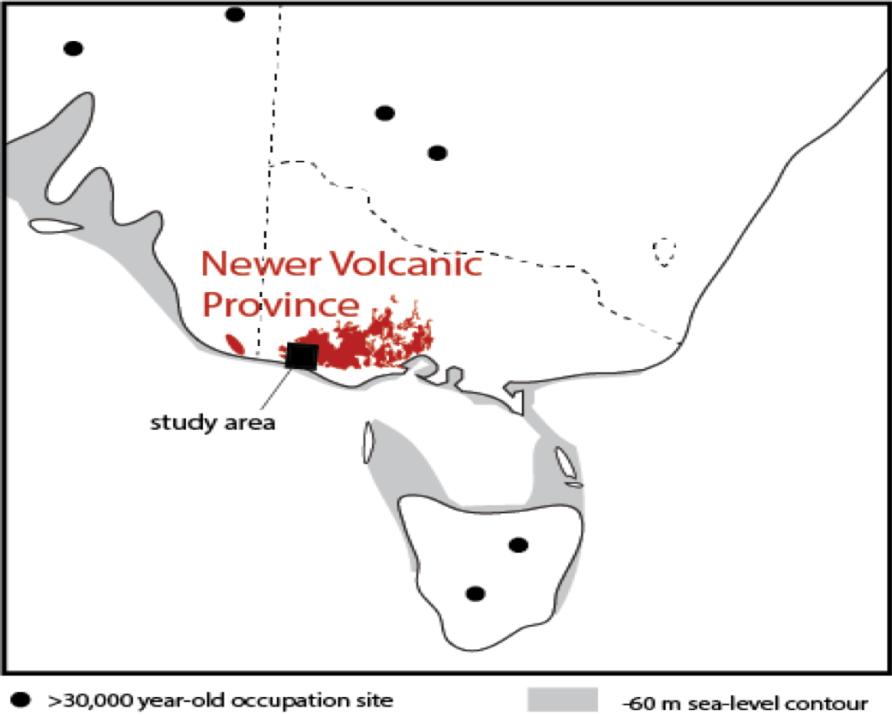

In southeastern Australia, only six sites (located in what are now Tasmania, New South Wales, and South Australia) older than 30,000 years are considered definitively dated by ¹⁴C and/or OSL methods, with ages spanning 37,000 – 50,000 years.

There is a need for independent age constraints to test some of the more controversial ages and add to the sparse age record.

The oral traditions of Australian Aboriginal peoples have enabled perpetuation of ecological knowledge across many generations, providing a valuable resource of archaeological information.

Some surviving traditions appear to reference geological events such as volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, and meteorite impacts, and it has been proposed that some of these traditions may have been transmitted for thousands of years.

Examples include oral traditions around the 7,000 year old Kinrara volcano in north Queensland, and a number of oral traditions implying much lower sea levels than present day and dramatic differences in vegetation reflecting cooler climates that existed thousands of years ago.

The plains of western Victoria and south eastern South Australia are punctuated by a number of conspicuous small hills and remarkably circular lakes.

These striking features are the remnants of volcanoes that are geologically very young. While the more than 400 individual volcanoes are considered to be extinct, the volcanic province of which they are a part, the Newer Volcanic Province, is regarded as active.

This region includes the youngest volcanoes in Australia, Mount Gambier and Mount Schank, both around 5,000 years old.

Although precise ages remain elusive, a number of other volcanoes in the Newer Volcanic Province are thought to have erupted within the last 100,000 years, and the people living in this region tens of thousands of years ago would no doubt have witnessed volcanic activity.

However, in Australia, little archaeological evidence has been found beneath volcanic ash deposits and lava flows – perhaps because very few studies have looked for this.

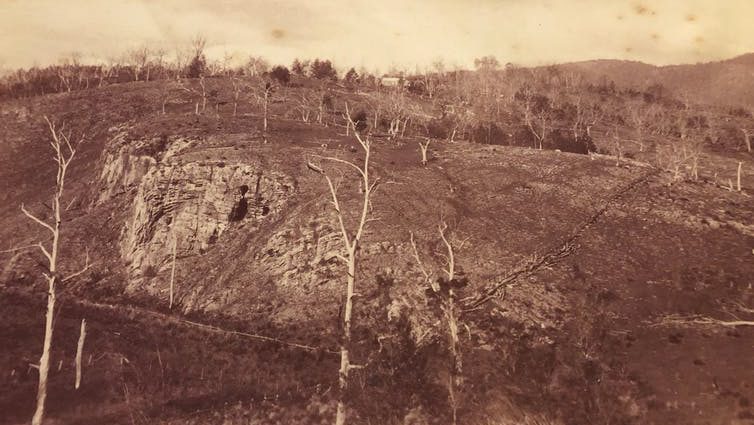

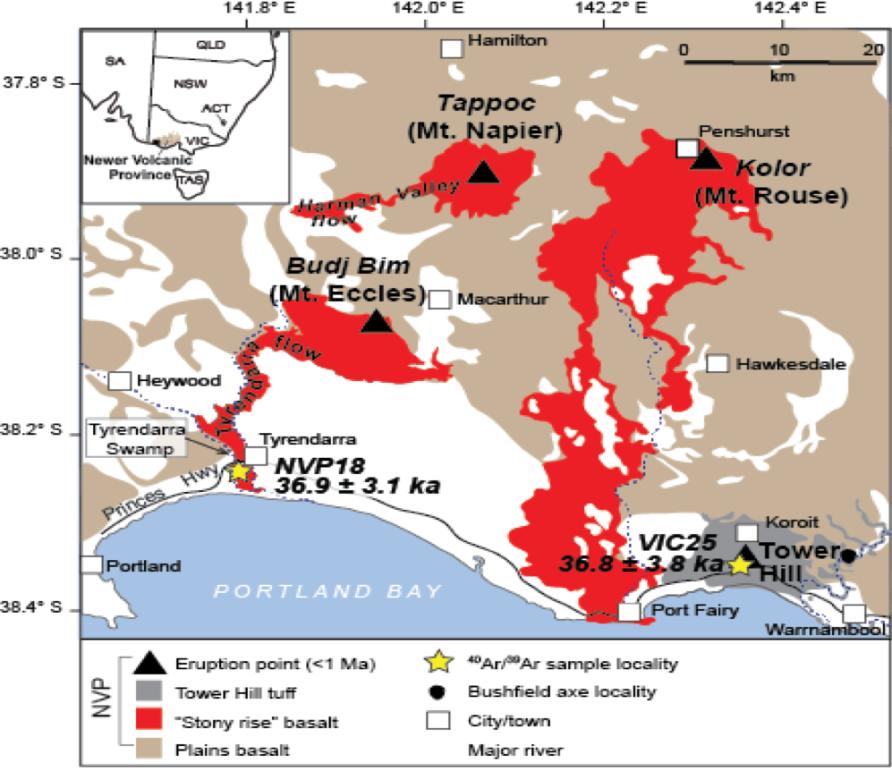

A single stone artefact, the ‘Bushfield axe’, was serendipitously discovered in the 1940s during sinking of a post hole through a sequence of finely layered volcanic ash from the Tower Hill Volcanic Complex, about 40 kilometres southeast of the Budj Bim Volcanic Complex (formerly Mount Eccles).

This ash from Tower Hill has not previously been dated.

The only previous estimation of the eruption age is from a combined OSL and ¹⁴C dating study of sediments above and below the volcanic ash, which gave an age of 35,000 ± 3,000 years.

However, that study did not consider the archaeological implications of this age, probably because the existence of the Bushfield axe is not widely known.

Previous ages for the Budj Bim Volcanic Complex are variable, largely derived from ¹⁴C dating of sediments in the crater lake (Lake Surprise) and swamps that formed after the lava modified the regional drainage system.

The oldest of these swamp sediment ages, ~31,400 ± 400 years, represents a minimum age for eruption of the Budj Bim Volcanic Complex.

This is consistent with ages of 33,600 ± 5,200 years and 39,600 ± 7,000 years determined by lava surface exposure dating methods, but the precise eruption age was not definitively known until now.

Another dating technique, called argon-argon (or ⁴⁰Ar/³⁹Ar dating) has been used to date much older volcanoes, including nearby Mount Rouse (284,400 +/- 1,800 years.

Technological improvements over the last decade, including work in our lab at the University of Melbourne’s School of Earth Sciences, have firmly established that ⁴⁰Ar/³⁹Ar dating, which relies on the rate of natural radioactive decay of potassium into argon in minerals, can be successfully applied to archaeological timescales.

In our study, published in the journal Geology, in collaboration with Professor Fred Jourdan and Dr Korien Oostingh at Curtin University, we applied the ⁴⁰Ar/³⁹Ar dating technique to a ‘lava bomb’ from the Tower Hill eruption sequence and to a sample from the Tyrendarra lava flow, the biggest lava flow from the Budj Bim Volcanic Complex.

This study was supported by a University of Melbourne McCoy Seed Fund grant with Museum Victoria and an ARC Discovery Grant.

These analyses produced lava eruption ages of 36,800 ± 3,800 years for Tower Hill and 36,900 ± 3,100 for the Budj Bim Volcanic Complex.

These ages fall within the range of ¹⁴C and OSL ages reported for the six earliest known occupation sites in southeastern Australia. The age of Tower Hill, associated as it is with the Bushfield axe, represents the minimum age for human presence in Victoria.

And if oral traditions surrounding Budj Bim do indeed reference volcanic activity, this could mean that these are some of the longest-lived oral traditions in the world.

This article was originally published in Science Matters.

Articles you may also like

In their own words: letters from ANZACs during the Gallipoli evacuation

Just five days before Christmas, in the early hours of Monday December 20, 1915, the last Anzac troops left Gallipoli in what Australian historian Joan Beaumont called an “elaborate game of deception”. Self-firing guns were rigged to take pot-shots and camp fires lit to give the impression of there being more soldiers than there were. The Australians […]