Hullo Wodonga you are our centre

You are the nest of Croat Ustashi

Fellow campers of Ante Pavelić

Wodonga again calls you,

All the camps which have been broken down will again rise.

(“Poem for Terrorism” 1972)

“From settlement,” wrote historian Jayne Persian, “Australia had been a country in which it was not only possible, but positively encouraged, to leave one’s past behind.”

Reading time: 14 minutes

Between 1947 and 1952, for 170,000 non-Jewish “displaced persons,” Australia offered a chance to exit the dark, harrowing night of World War II in Europe. Many of these were hungry, traumatised, seeking peace and shelter, a place to work and rebuild. But with them came the kind of settlers which populate nightmares: war criminals, outright fascists, and aiders and abettors of the Nazi regime and its puppets in Eastern Europe.

By Morgan W.R. Dunn

The most lasting of these is the Ustaše. A fascist movement launched in 1929 in Croatia, in 1941 this group came to power in a German puppet state called the Independent State of Croatia (Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, or NDH). And in the chaos of the postwar era, they found a new home on the other side of the world.

Origin: the Early Years of Ustashism

No one in Yugoslavia would have guessed that Ustaše would one day take centre stage in Croatian independence. In August 1928, a Montenegrin Serb assassinated Stjepan Radić, leader of the Croatian Peasant Party. King Alexander I, an ethnic Serb monarch who sought to forge a single Yugoslav identity among a dozen nationalities in his kingdom, seized the chance to further his Yugoslav nationalist goals by declaring himself dictator in January 1929.

Lawyer Ante Pavelić, a fervent Croatian nationalist born under Austro-Hungarian rule, fled to Vienna and established the Ustaše (“rebels” or “insurgents”) in exile. With financial backing and training from Bulgaria and Austria through sympathetic Macedonians, and especially from Benito Mussolini’s Fascist Italy, Ustaše militants assassinated Alexander in October 1934 with Mussolini’s support and encouragement.

Banned in Yugoslavia from 1937, Ustaše regained prominence through Germany’s war in the Balkans. Yugoslavia, under pressure from Germany and Italy, joined the Axis powers in late March 1941. Almost immediately, a coup placed Alexander’s son Peter II on the throne and stepped back from the Axis. Adolf Hitler, already planning to invade the Soviet Union, couldn’t afford a large, populous opponent in the south. Two weeks after the coup, Axis troops invaded the kingdom and destroyed it.

On 10 April 1941, the Independent State of Croatia (Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, or NDH) was established. Pavelić was duly installed as the Poglavnik (“leader,” analogous to Führer or Duce) of the new regime.

The NDH was a source of manpower for the Eastern Front and resources for the German war machine. At heart, however, it was a puppet state and a regime of murder. Pavelić oversaw concentration and death camps. Jasenovac, the third-largest extermination camp in Europe, exhibited “brutality” that, notes terrorism scholar Kristy Campion, “challenged the systematic extermination of other camps, as internees were killed one by one, with hammers, bludgeons, knives, and bullets.” 30,000 Jews were virtually wiped out, 25,000 Roma murdered, and over 320,000 Serbs killed. Thousands more Serbs were forcibly “Croatized.”

Nothing could halt the advance of the Allies, however. By May 1945, Yugoslav Partisan, Bulgarian, and Soviet troops crushed the NDH. Pavelić fled abroad, later reestablishing Ustaše in Argentina and dying in Spain in 1957 after an assassination attempt. His followers dispersed: by 1948, the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) had noted the arrival of the first Ustaše members in Australia.

Ustaše in Australia

The ashes of Pavelić’s regime were scarcely cold before its adherents found a haven in Australia. While most Croatians settled peaceably, many former NDH officials arrived, prompting ASIO head Charles Spry in 1948 to note that “members of Ustaschi organisations should be regarded as being of security interest by virtue of their fascist sympathies.” ASIO nonetheless looked the other way. These arrivals quickly founded pro-Ustaše social clubs and newspapers. Tensions arose just as quickly within a society shaped by “the ‘White Australia’ policy in which all non-British migrants were tolerated but viewed with a certain degree of suspicion.”

This isolation aided Ustaše recruitment as activists challenged the pro-communist Yugoslav Immigrants Association of Australia. Persian writes that Catholic organisations under Ustaše

“were alleged to have sent representatives to meet arriving ships and into Australian migrant camps, guaranteeing jobs and homes, and lending money; any refusal to pay Ustaše levies (£12/year in 1961) was met with threats and, if necessary, violence… Even military training camps were often mandated as compulsory attendance for recruits. These young Croatians, who held valuable Yugoslav citizenship, were seen as particularly useful for the fight ahead.”

“The main strength of Ustaše in Australia,” wrote the anti-Ustaše activist Marjan Jurjević, “is based upon the ability of the various organisations, aided by the Croatian Catholic Church, to continually draw fresh recruits from the newcomers arriving from Yugoslavia and camps in Europe.”

Within the movement itself, too, there was friction. There was not one major Ustaše organisation in Australia but three, none of which used the name for their own groups. Nevertheless, with leaders and experience drawn from the NDH, Ustaše was “in their hearts.”

First was the Croatian Liberation Movement (HOP) founded in Argentina in 1956 and headed in Australia by Fabijan Lovokovic, Pavelić’s former bodyguard, who revived the NDH newspaper Spremnost. Next came the Croatian National Resistance (HNO), founded in 1957 by General Vjekoslav ‘Maks’ Luburić, a former commandant of Jasenovac concentration camp and the Black Legion, the NDH’s answer to Germany’s SS-TV. HNO had split from HOP over Pavelić’s willingness to barter Croatian territory. Leading HNO in Australia was Srećko Rover. He too ran a newspaper, Hrvat (The Croat), which included “‘pro-Nazi, anti-democratic and anti-Semitic content.”

Finally, there was the most notorious of the three, the Croatian Revolutionary Brotherhood (HRB), founded in 1961 by several young members of HOP who were frustrated that the organisation “did not support the creation of a Croatian State by terrorist and revolutionary means.” For these radicals, Australia was “the citadel of Croatian national consciousness abroad.”

Raiders in Yugoslavia

Charles Spry had changed his mind in the years since 1948. Now, the Director-General saw right-wing émigré groups as “good anti-communists.”

Ljubomir Vuina was a former Black Legion colonel and founder of the first Australian Croatian Club in Adelaide, where 60% of the members were thought to be ex-Ustaše. When Vuina applied for permission to publish a Croatian-language newspaper in 1951, Spry insisted that there was “insufficient evidence available for a security objection to be raised to the publication of the proposed paper.”

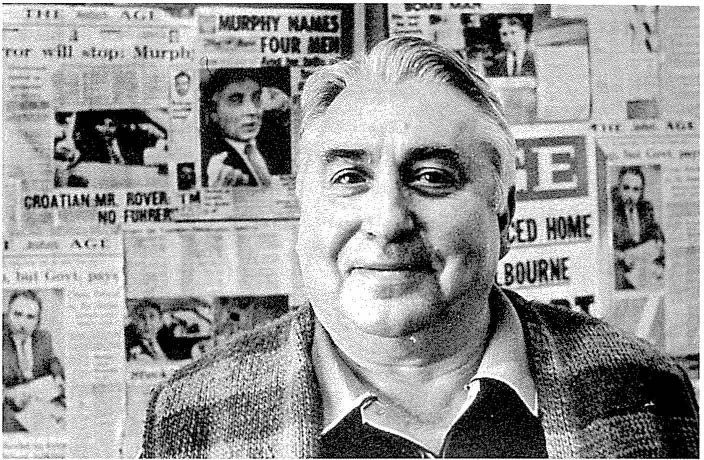

In 1953, an ASIO report warned that Srećko Rover and Drajutin Sporish’s Hrvat was becoming “the official organ of Fascist propaganda in Australia.” Despite ASIO’s assessment of Sporish as “an ardent fascist and a man who would stop at nothing to gain his own ends,” and the AHD’s “pro-Ustase policies and its contacts ‘with the Croatian terrorist Ante Pavelich,’” Spry had “no security objection” to Hrvat because ‘the Australian Croatian Association is anticommunist and anti-Tito.”

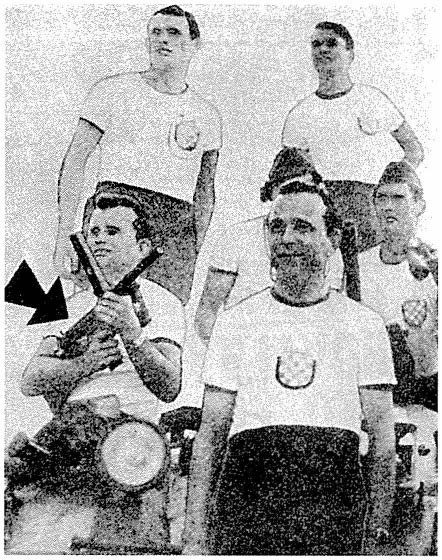

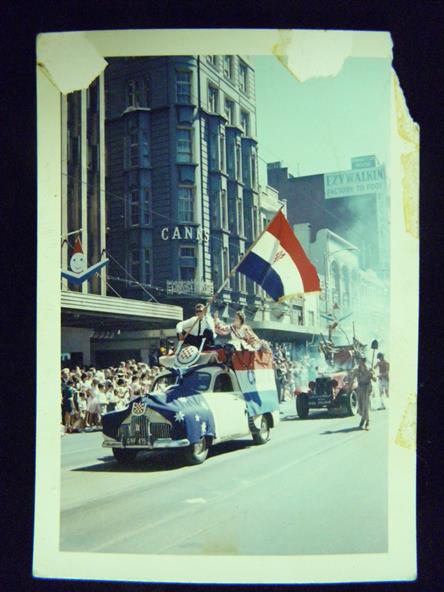

Public exposure came in January 1963, when Spremnost published an article on HOP paramilitary training facilitated by Australian Army personnel in Wodonga, Victoria, complete with a photograph of HOP militants on an armoured car. Answers were demanded in the Senate; Minister for the Army John Cramer dismissed the event as a recruitment effort involving a “picnic group.”

That July, nine Croatian-Australian HRB militants were captured in Yugoslavia on a sabotage mission. In court, they claimed they were trained by Father Rocque Romac, actually Father Stjepan Osvaldi-Toth, a former NDH official who had sponsored the Nazi fugitive Klaus Barbie’s immigration to Bolivia.

Australia’s international embarrassment prompted further questions. A description of Australian Ustaše as “neo-fascist” was likened by a Liberal Party politician to McCarthyism. Liberal minister William McMahon countered that they were “a good bunch” with “a good cause.” ASIO again recommended turning a blind eye.

From 1963, Ustaše terrorism escalated. In 1964, Tomislav Lesić, a young Croatian-Australian with Ustaše links, lost his legs when a suitcase bomb meant for the Yugoslav Consulate in Sydney exploded prematurely. Death threats were common. A frequent target was Marjan Jurjević, who commented that “the Ustaše know that if the public understands what they are doing, they will be very quickly dealt with, so they must try to intimidate anyone who opposes or tries to expose them.”

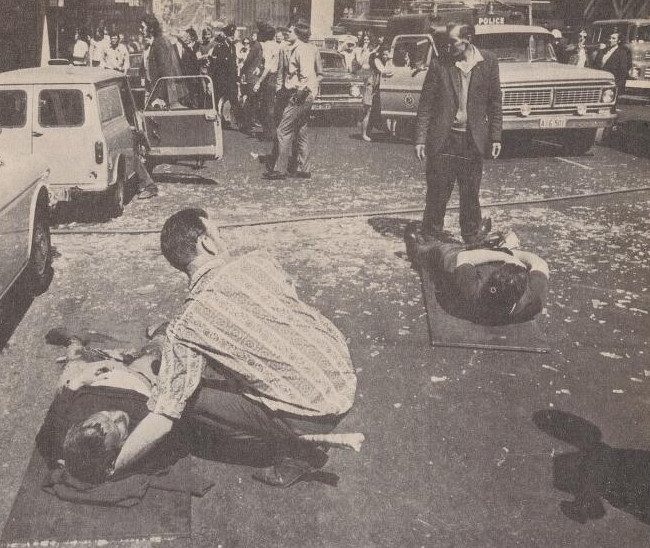

Ustaše methods intensified. In March 1969, two men alleged to have inside information on the Ustaše were found shot, execution-style, in the Melbourne suburb of Caulfield. In June, the Yugoslav Consulate in Sydney was bombed, as was the Yugoslav Embassy in Canberra in November. In January 1970, the Serbian Orthodox Church in Canberra was also bombed. Croats were convicted or suspected in all the attacks, but none were deported. In 1971, the Soviet Embassy, another Orthodox church, and a cinema showing Yugoslav films were bombed. All of this would pale in comparison to 1972.

Blowback at Home

1972 was the pinnacle of Australian Ustaše activity. January saw another church bombing. Late that month, a Yugoslav airliner was blown into three pieces in the air over East Germany, killing 27 of the 28 aboard. Croatian Australians were implicated. In April, two more bombings took place, one targeting a migrant centre and the other the home of Marjan Jurjević.

In June, 19 HRB men, including Australian citizens and three Australian residents, crossed the Yugoslavian border from Austria through the town of Dravograd. According to HRB head Jure Marić, they “intended to give hope and inspiration to the people of Croatia who were suffering much after Tito’s hard-line clampdown on Croatia after the Croatian Spring [a brief nationalist upsurge] in 1971.” This “Bugojno Group” hijacked a truck to enter Yugoslavia; the local driver immediately sounded the alarm, triggering the largest deployment of Yugoslav Territorial Defense forces in history. Over the course of five days, 13 Yugoslav militiamen lost their lives and 14 were wounded. 15 of the Bugojno militants were killed and the remainder captured and tried.

“Operation Phoenix” was a disaster for the HRB and a humiliation for the Australian state, whose leaders still insisted that there was no Ustaše activity in the country. Belgrade “as if [Ustaše activity] involved a threat to the regime and to the survival of the federal state.” Ivor Greenwood faced fresh outrage from the Labor Party, which demanded to know why there had been “such a lack of success in apprehending those responsible for the terror campaign here.”

Part of the reason lay in the political success Ustaše-linked figures, and other politicians affiliated with the “Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations” (ABN), enjoyed in the Australian government. Ljenko Urbančič, a former propagandist for the pro-Axis Slovene Home Guard, headed the “Migrant Advisory Council,” an ABN front which, during the 1970s, controlled “up to one-third of the votes at the 800-member State Council” of the New South Wales Liberal Party. For Liberal Party politicians, blocs of ABN votes were vital election-winning weapons.

The attacks into Yugoslavia, and the increasing absurdity of denying the existence of Ustaše in Australia, were a growing embarrassment for the decade-old Liberal government. But the Ustaše were about to reach the end of the line: 1972 was an election year.

Murphy’s “Raid” and the End

In December 1972, Gough Whitlam led the Labor Party to its first electoral victory since 1946. The new prime minister brought a hard line on right-wing terrorism, and to enforce it, he brought with him a new Attorney-General, Lionel Murphy.

Murphy’s security adviser, Kerry Milte, alleged that ASIO had been concealing information on Croatian terrorism as well as the World War II activities of right-wing émigré leaders. In March 1973, the attorney-general dramatically broke down the door of the ASIO office in Canberra looking for Milte’s evidence, ostensibly to ensure the safety of visiting Yugoslavian Prime Minister Džemal Bijedić.

Murphy found nothing conclusive. Nevertheless, the “raid” made it plain that Murphy was serious when he’d declared that “terrorist activity will no longer be tolerated in Australia.” By the end of the decade, new laws made it a crime to support or plan attacks on foreign states and to illegalise émigré leaders passing themselves off as consular officials.

The final blow came in 1979, when an ABC radio documentary revealed Ljenko Urbančič’s wartime past. Urbančič fell from political grace and was forced to disband the Liberal Ethnic Council, successor to the Migrant Advisory Council. Yugoslavia would never again have to contend with another Ustaše attack.

The active threat may have ended, but the legacy of Ustaše reverberates in Australian political culture to this day. There are no more active militants, training camps, or funding networks, nor assassination plots or bombing campaigns.

Ustaše flags are flown by supporters at matches, and chants of the Ustaše slogan Za dom, spremni! (“for homeland, ready”) can be heard in stadiums. Srećko Rover was a founder of Melbourne Knights FC. Perhaps the most worrying aspect of this legacy is what it means to new generations. In the opinion of Australian National University researcher Alexander Lee, “If you look at the number of people who actually speak Croatian in Australia it’s less than a third of the people of Croatian background. I don’t know if they know what these things mean.”

Podcast episodes about Ustaše

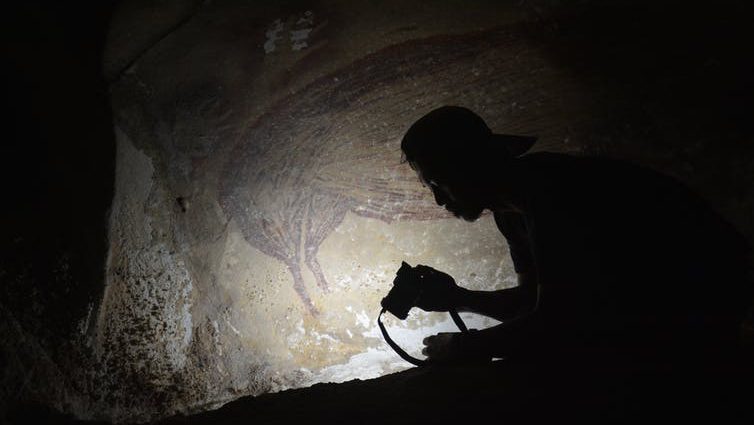

Articles you may also like

Home Made Wings – Australian Military Aircraft Manufacturing – Video

This documentary explores the history of Australian military aircraft manufacturing. Australia had just completed its industrialisation in 1939, becoming a full war economy very rapidly.

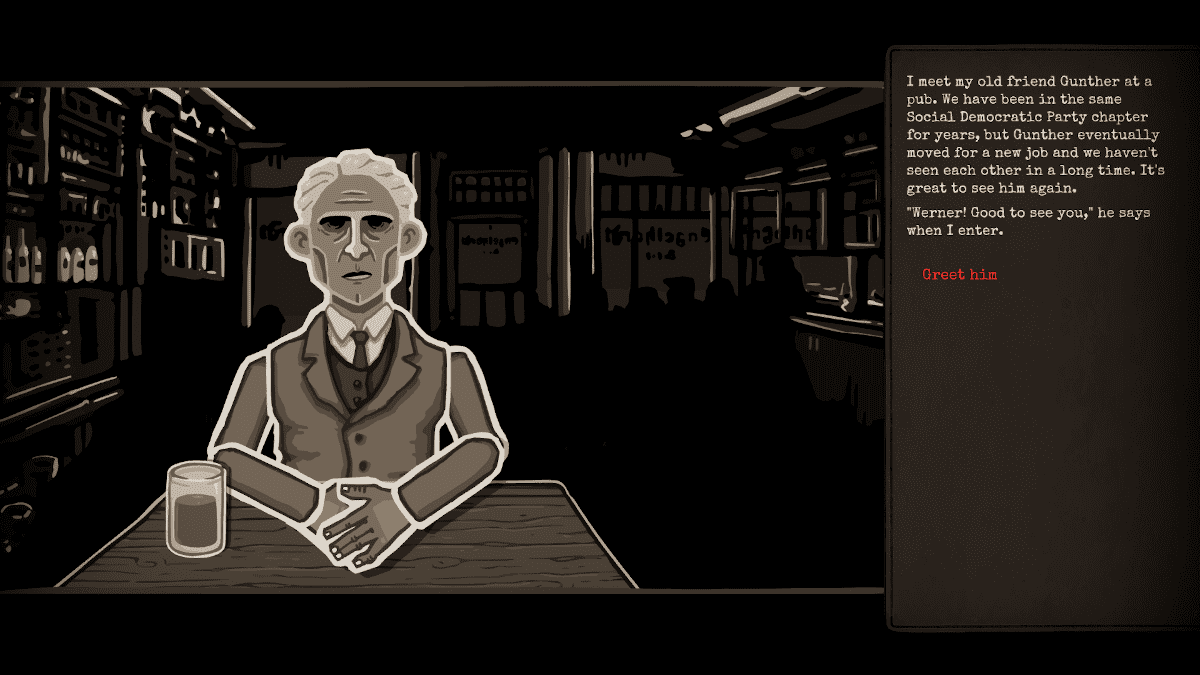

Four Video Games That Actually Teach History

Reading time: 13 minutes

There are plenty of video games that use historical backdrops for their narrative, or even entice you to recreate history in some way. As we discuss with historian Pieter van den Heede in our article on whether games can teach history, the question remains of how much you actually learn while playing these games. Thankfully, some do a much better job than others, and in this article, I will go over four of them.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.